Bharadia L, Moidutty S, Panda M, Hegde R. Diagnosis and management of pedatric GERD in real world practice: A Questionnaire-based survey among Indian pediatricians (GERDCIP Study). Poster presented at: Pedicon 2019. 56th Annual Conference of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics; 2019 Feb 6-10th; Mumbai, India

Background

- Pediatric GERD has become a common problem in the pediatric age group and has shown upward trend over the past decades.1

- It difficult to diagnose, as symptoms are diverse and often difficult to interpret.2

- Accurate diagnosis, appropriate management strategies, and timely referral to specialist are important principles in the effective management of GERD.3

- There is a scarcity of literature on GERD in children from India.4

Aims and Objectives

This survey was conducted to comprehend the existing disease trends of GERD in children and its management.

Materials and Methods

A real world questionnaire-based survey was conducted amongst Indian pediatricians using MCQs.

Results

- A total of 149 pediatricians responded to the survey.

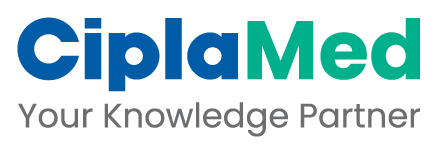

- Over 50% respondents diagnosed GERD in about 6-10% of children in their daily practice.

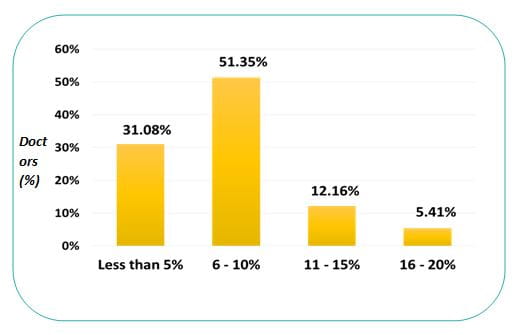

- Two common GERD manifestations in infants apart from regurgitation were poor weight gain and generalised irritability (46% & 29% respondents).

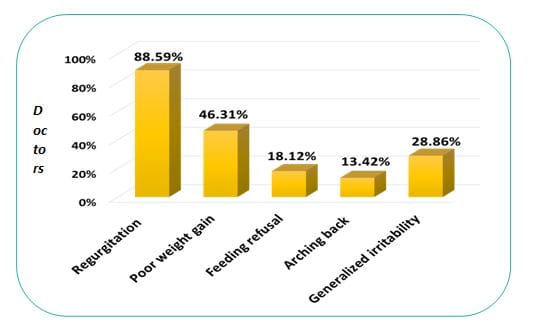

- Recurrent vomiting and abdominal pain were frequent presentations in older children according to 66% and 45% respondents, respectively.

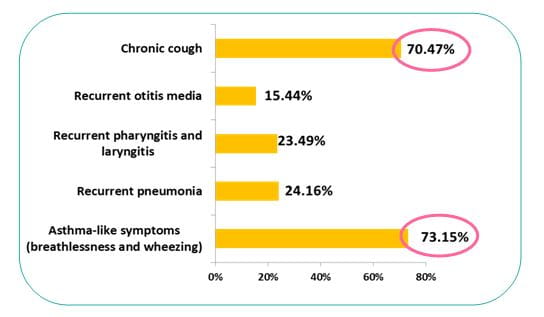

- Majority of the pediatricians (46%) observed extra-esophageal manifestations in 5-15% of GERD patients. Asthma-like symptoms and chronic cough were the most common extra-esophageal symptoms according to 73% and 70% respondents, respectively.

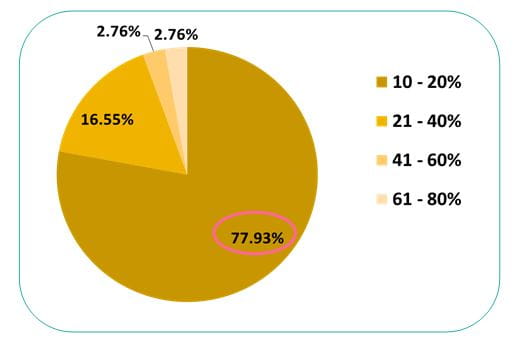

- More than 1/3 of the total pediatricians chose to treat 10-20% of asthma patients.

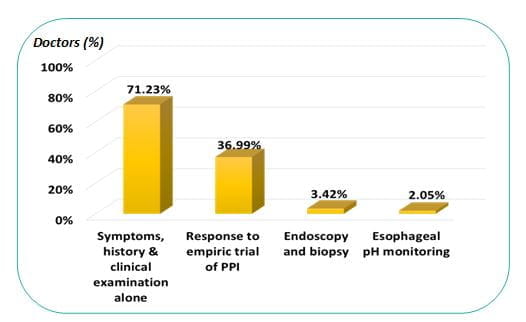

- Nearly, 72% respondents labelled GERD diagnosis on basis of history and clinical examination.

- About 37% pediatricians labelled GERD on the basis of response to empiric PPI trial.

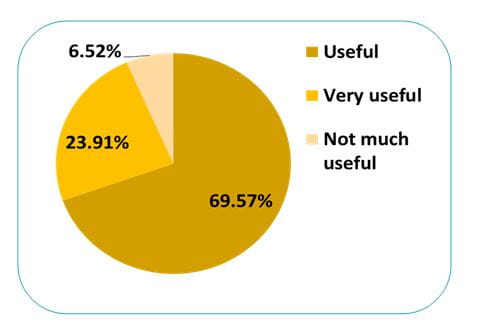

- 70% pediatricians agreed on the usefulness of Orenstein’s scale for diagnosis of GERD in infants, though only 32% of them used it.

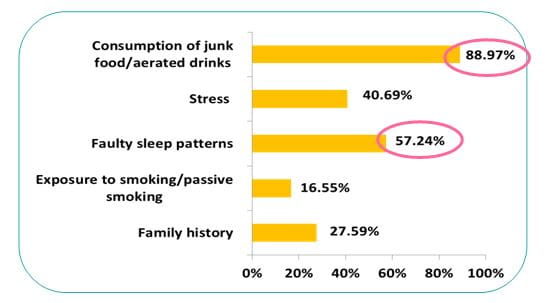

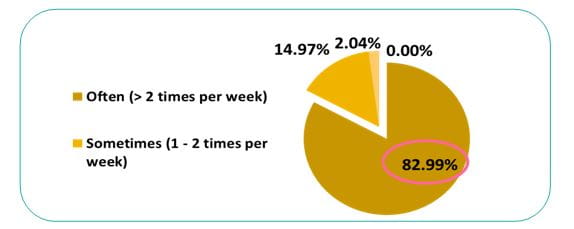

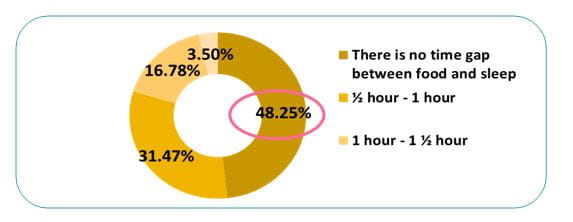

- Most pediatricians reported a strong correlation between faulty lifestyle and GERD. Frequent consumption of junk food/ aerated drinks (> 2 times/ week) and erratic sleep pattern with no much gap between sleep and meals were most common factors associated with GERD.

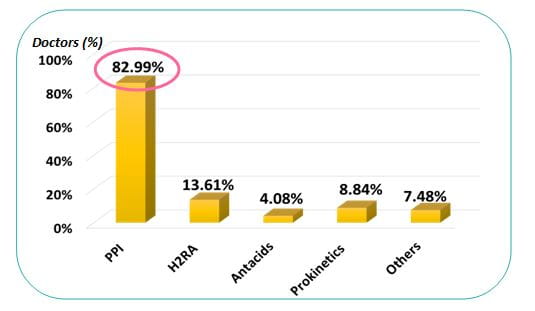

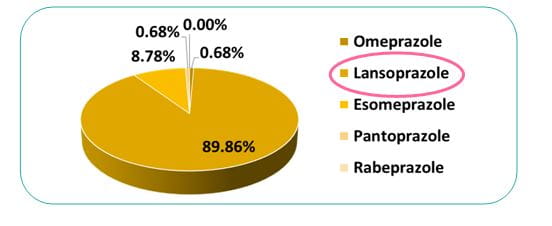

- PPI was opted as first line of therapy by majority of pediatricians (83%) with preference for lansoprazole by 90% of them.

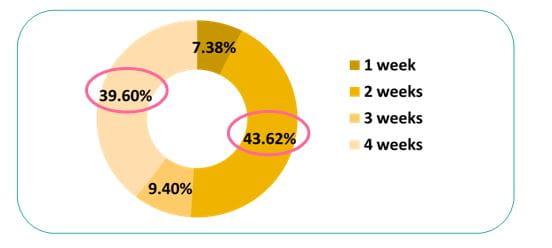

- About 44% and 40% respondents chose either a 2 or 4 week PPI empiric trial, respectively.

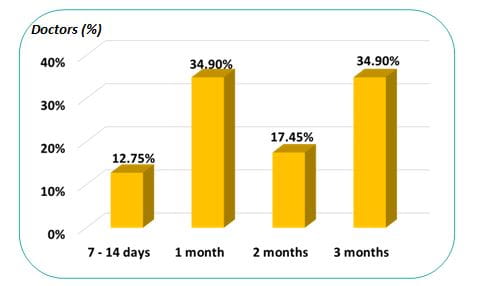

- 65% pediatricians treated GERD for less than 3 months, which was lesser than the recommended duration.

- Apart from symptomatic relief, the desirable goals while treating GERD were, achieving better quality of life and prevention of complications

|

Symptomatic relief |

62.42% |

|

Healing of the esophageal mucosa |

44.30% |

|

Prevention of complications |

55.70% |

|

Better quality of life |

58.39% |

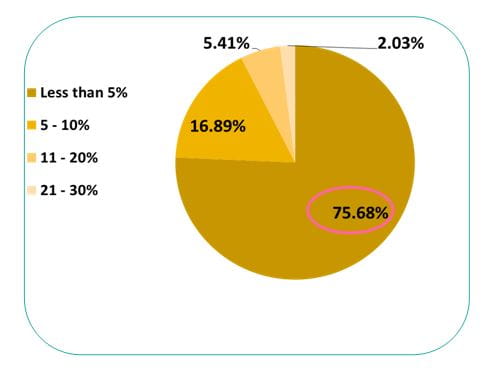

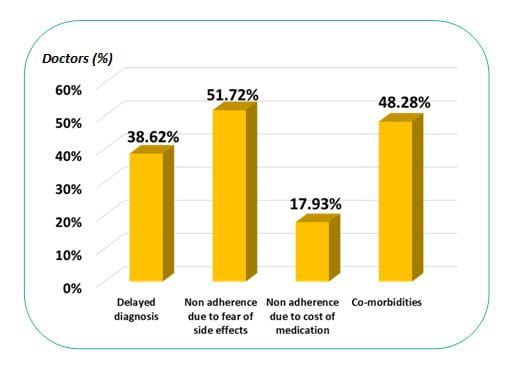

- Most pediatricians (76%) reported that fewer than 5% of patients had uncontrolled GERD post-treatment; most common reasons stated were therapy non-adherence (52%), presence of co-morbidities (48%) and delayed diagnosis (39%).

- About 85% of paediatricians referred uncontrolled GERD to a specialist.

Observations and Discussion

Epidemiology

- Prevalence of GERD in regurgitant infant and children is 30.8% in India5

- Contrary to the previous held belief, prevalence of GERD in India is in fact much higher and similar to that reported in the western world.1

- Traditionally GERD thought to be uncommon in developing countries; studies in multi-ethnic population showed people of Indian origin at higher risk of GERD than ethnic Malay and Chinese.1

Diagnosis

- Indian Health care professionals overlook GERD in differential diagnosis.1

- No gold standard for GERD diagnosis; no single test sufficient to make its reliable diagnosis.4,6

- Several conformational studies* for GERD available only in selected centres thus limiting its use.1

- Because of its simplicity (just 20 min to complete) and reproducibility, iGERQ can be used to identify infants who need further evaluation.7

- Empiric therapy with PPI significantly decreases need for extensive evaluations8

o Out of 100 children (mean age: 9.4± 4.2 yrs) with suspected GERD, 78% responded to empiric PPI of 2 wks

o Monotherapy of PPIs alone was sufficient; 94% patients used lansoprazole as single PPI

o Significant decrease in symptom scores noted even at 1st week of study

o Empiric treatment as initial treatment found to be more cost effective than other approaches

- A proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial is a valuable diagnostic tool for GERD.6

- Greatest symptomatic improvement occurs in the first 2 to 4 weeks of PPI administration4

|

IAP 20134 |

An empirical trial of upto 4 weeks is justified in older children and adolescents with classical symptoms of GERD |

|

NASPGHAN /ESPGHAN 2018 9 |

A 4 to 8 week trial of PPIs for typical symptoms (heartburn, retrosternal or epigastric pain) in children as a diagnostic test for GERD. In symptomatic infants where referral to a pediatric GI is not possible, consider 4-8 week empiric trial, then wean if symptoms improve. |

|

NICE 201510 |

Consider a 4 week trial of a PPI or H2RA for children and young people with persistent heartburn, retrosternal or epigastric pain. |

|

AAP 201311 |

Older children with heartburn may benefit from empirical treatment with PPIs for 2 weeks |

Risk factors1

- GERD is a well-documented disease in infants and affluent middle aged.

- With spread of means of mass communication like television, children of rural area too have started consuming fast food, aerated drinks etc.

- These life-style changes may subtly contribute to the burden of GERD.

- Simple measures like eating small and frequent meals and to avoid lying down 3 hrs after a meal might help this group of patients.

|

Dietary and life style parameters |

GERD symptoms |

?2 test |

|

Ingestion of tea/coffee |

53/194 |

P<0.001 |

|

Spicy (very and some) |

60/229 |

P<0.001 |

|

Aerated drinks |

47/60 |

P<0.001 |

Limitation

- Number of pediatricians (N=149) in the survey was much lesser than universe of pediatricians in India (20,000+)

- Survey was in MCQ format and not open ended; answers/information were captured from the limited given options.

Conclusion

- GERD in Indian children is diagnosed on basis of history, clinical examination and response to treatment.

- Lansoprazole is the most preferred medication for GERD.

References

1. Int J Med Public Health 2013; 3: 321-4

2. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Mar;11(3):147-57

3. Paediatr Drugs. 2012 Apr 1;14(2):79-89.

4. Indian Pediatr. 2013 Jan 8; 50(1):119-2

5. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2018 Mar;5(2):395-399

6. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1671

7. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2018 Aug 6:1-6.

8. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 2015; 57 (5): 482-486

9. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018; 66 (3) :516-554

10. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in children and young people: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines 2015

11. Pediatrics. 2013 May;131(5):e1684-95