Epidemiology and Burden of Allergic Rhinitis: 500 Million and Still Counting…

Allergic rhinitisis a very common disorder that affects people of all ages. According to the Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) guidelines, allergic rhinitis affects 500 million people worldwide and over 100 million in India, Pakistan and surrounding countries. More number of people suffer from allergic rhinitis than other chronic diseases such as asthma and diabetes.

Allergic rhinitis develops before the age of 20 years in 80% of cases, peaking in adolescence. Interestingly, in childhood,the male gender is more susceptible but the ratio equalizes in adulthood. Previous studies have observed increased prevalence in polluted urban areas, people of non-Caucasian origin and, curiously, in first-born children.

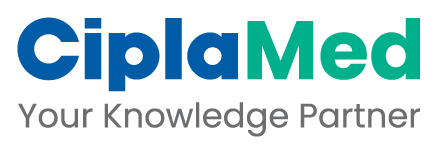

The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) project investigated the prevalence of allergies, including allergic rhinitis, in children who were 13–14 years of age. The ISAAC Phase I compared prevalence between countries while the ISAAC Phase III assessed prevalence after 5 years of Phase I. It revealed an increased prevalence of allergic rhinitis (in the Asia-Pacific region) in countries such as India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and China (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence (%) of allergic rhinitis in children in the Indian subcontinent and the Asia-Pacific region during the ISAAC Phase I and III

For instance in the United States of America (USA),allergic rhinitis accounts for 16.7 million physician office visits, 3.5 million lost work days and 2 million lost schooldays each year,thereby having a significant socio-economic impact on the sufferer.The condition alsoresults in a twofold increase in the medication costs.

Patients with allergic rhinitis also frequently suffer from other forms of allergic diseases such as asthma. It is estimated that more than 40% patients with allergic rhinitis have asthma and, conversely, more than 80% of asthmatic patients have concomitant rhinitis.

One of the consequences of allergic rhinitis is sleeping disorders, leading to daytime fatigue and somnolence as well as decreased cognitive functioning. In children, an off-shoot of this could be learning, behaviour and attention impairment. Up to 57% of adult patients and up to 88% of children with allergic rhinitis have sleep problems.

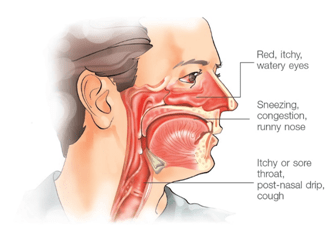

Since allergic rhinitis is a symptomatic disorder, symptoms are the most bothersome aspect of the disease. In an extensive survey conducted over telephone with 2,500 Americans, it was revealed that the most troublesome symptoms for patients with allergic rhinitis are a stuffy and runny nose, post- nasal drip, red, itchy, watery eyes, repeated sneezing, headache, nasal itching, and facial and ear pain. These physical symptoms also have psychological effects such as fatigue, irritability, anxiety, depression, frustration, self-consciousness, and lower energy, motivation, alertness and ability to concentrate.

Though the symptoms by themselves are not life-threatening, they can have an adverse impact on the patients in terms of social isolation, activity limitations, limited visits to friends and family and an inability to visit open spaces such as parks and closed spaces (such as restaurants, cinemas).

On an average, patients with allergic rhinitis usually use two or more medicines to treat their allergic rhinitis. Self-medication with over-the-counter, sedating antihistamines results in drowsiness and further impairment of cognitive and motor functions.

Life with Allergic Rhinitis

As mentioned previously, allergic rhinitis per se is not a life-threatening disorder. The symptoms such as sneezing, itching, rhinorrhoea and congestion do cause discomfort. However, it is the frequency and severity of the symptoms that can greatly affect the overall well-being of individuals with allergicrhinitis.

Unlike many other diseases whose treatment is aimed towards preventing death or future morbidity, the goal of treatment in allergic rhinitis is to improve a patient’s well-being or quality of life.

Despite the troublesome nature of the symptoms, many people with allergic rhinitis do not seek medical treatment and, instead, opt for self-treatment with home remedies and over-the-counter medicines.

The reason for this may be that allergic rhinitis is perceived by both patients and physicians as less important than other airway diseases such as asthma. However, allergic rhinitis is responsible for significant societal and economic costs than is realized. In the USA alone, allergic rhinitis results in 3.5 million lost workdays and 2 million missed school days each year.

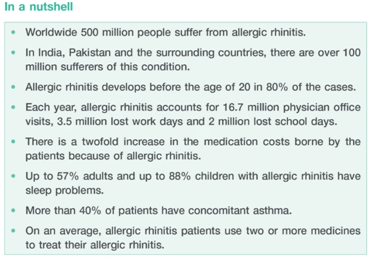

In a survey of 312 individuals with nasal and ocular symptoms, it emerged that individuals experienced at least 31 days of rhinitis symptoms in a year, which impaired the quality of life, particularly with respect to their ability to perform normal physical activities (Figure 2A and B). The major reasons for an impaired quality of life were repeated nose blowing, disrupted sleep patterns and inability to concentrate.

Figure 2A and 2B: Quality of life as measured by questionnaires in individuals with nasal and ocular symptoms (coloured circles) versus healthy individuals (white circles).

*P<0.01 versus controls, †P<0.05 versus controls.

Additionally, both children and adults with allergic rhinitis have sleep disturbances, probably because of nasal congestion. Studies have also shown that chronic rhinitis is an important risk factor for developing sleep disorders.

Uncontrolled symptoms at night, leading to loss of sleep and the resulting daytime fatigue, may also contribute to learning impairment and absenteeism. It has beensuggested that severe chronic upperairway disease may arise when the rhinitis is not controlled by adequate pharmacotherapy. This disorder could affect some 20% of people with rhinitis, with concomitant severe effects on the quality of life and work and school ability.

Understanding the Disease Process and Its Natural History

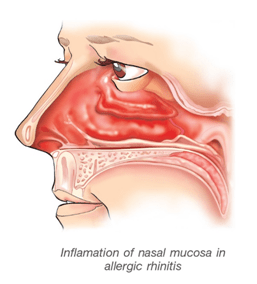

Allergic rhinitis, is an inflammatory disorder of the nasal mucosa characterized by symptoms such as sneezing, nasal itching, rhinorrhoea and nasal congestion caused due to an IgE-mediated allergic reaction.

Figure 3: Inflammation of nasal mucosa in allergic rhinitis

This disorder is initiated by an allergic immune response to inhaled allergens such as dust mites, pollens, fungal spores, animal dander, etc., in atopic individuals.

Atopic individuals have a genetic predisposition to become sensitized to harmless allergens. This immune response takes place as described below:

Sensitization to Allergens

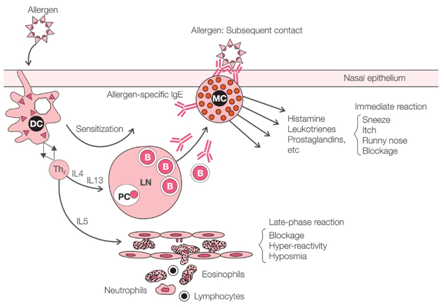

The sensitization is mediated via activation of the dendritic cells and T-lymphocytes. Dendritic cells are strategically located at mucosal surfaces to capture allergens and act as antigen-presenting cells to circulating T-lymphocytes. The result is anallergic response by a T-helper 2 (Th2) cell. Activated Th2 cells secrete several cytokines. One such cytokine is the interleukin-4 (IL4), which induces the B cell to release specific IgE. IgE molecules are released into the bloodstream and bind to the high-affinity receptors on the surface of tissue mast cells and circulating basophils (Figure 3). The IgE binding to mast cells stimulates them and various mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, etc., are released subsequently when the allergens are again deposited onto the nasal mucosa of sensitized individuals.

Early and Late Allergic Reactions

When allergic rhinitis patients are exposed to allergens, allergic reactions develop in two different patterns according to the time sequence. One is the early reaction, in which sneezing, nasal itching and rhinorrhoea develop in 30 minutes. These early symptoms are the consequence of the rapid release of preformed histamine, prostaglandins and leukotrienes from sensitized mast cells. The early reaction is the response to the mast cells to offending allergens and is a type I hypersensitivity reaction (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Pathogenesis of allergic rhinitis

Key: DC: Dendritic cell, LN: Lymph node, PC: Plasma cell, B: B cell,IL: Interleukin; Th2: T-helper 2 cell

The other pattern is the late reaction, which shows nasal obstruction approximately 6 hours after exposure to allergens. In contrast to the early reaction, eosinophil chemotaxis is the main mechanism in the late reaction, which is again caused by the mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandin D2 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha,all of which were newly generated in the early reaction (Figure 3). Several inflammatory cells, eosinophils, mast cells and T-cells migrate to thenasal mucosa, breaking up and remodelling normal nasal tissue, resulting in nasal obstruction, which is the main presenting symptom of the late allergic reaction.

Animportant feature of allergic inflammation is non-specific hyper-responsiveness. Due to eosinophilic infiltration and destruction of the nasal mucosa, the mucosa becomes hyper-reactive to normal stimuli and causes nasal symptoms such as sneezing, rhinorrhoea, nasal itching and obstruction. This is a non-immune reaction that is not related to IgE. Hypersensitivity to non-specific stimuli such as tobacco or cold and dry air as well as specific allergens increases in allergic rhinitis.

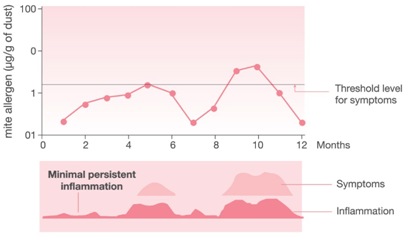

Minimal Persistent Inflammation (MPI): A Cause for the Chronicity of Allergic Rhinitis

The concept of MPI is an important hypothesis that has been proposed and confirmed in allergic rhinitis. MPI is defined as an inflammatory process that is actually present even in asymptomatic subjects who are exposed to allergens. The concept of MPI stems from the belief that even when the allergen is absent or at a low concentration, the inflammatory processes are active in the nasal mucosa due to self-maintaining mechanisms mediated through epithelial cells, some neuropeptides and some enzymes (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The concept of minimal persistent inflammation

Therefore, patients with allergic rhinitis have underlying inflammation in the nasal mucosa all throughout their life span. When the allergen load in the environment increases, the inflammation increases,thereby giving rise to the symptoms of allergic rhinitis. On receiving treatment, the inflammation reduces but is still persistent at a minimal level in the nasal mucosa, thus rendering the patient asymptomatic.

Natural History

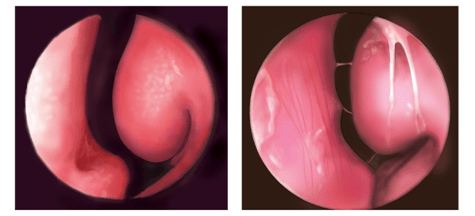

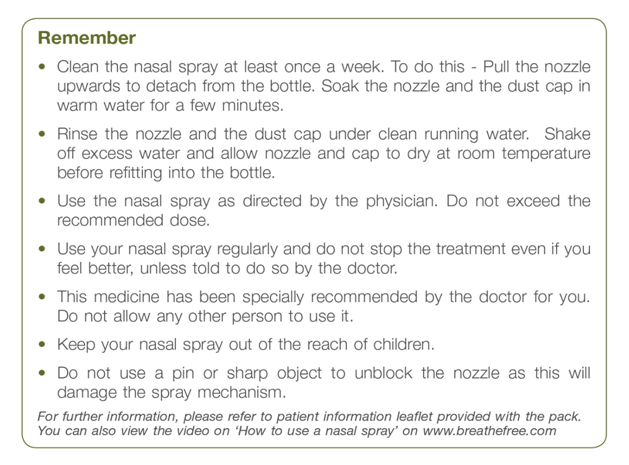

In the early years of the allergic disease, the inflammation and hypersecretion result in a pale-looking nasal mucosa, oedema of the middle and lower turbinates, increased watery secretion, itching, sneezing, rhinorrhoea and nasal congestion (Figure 6Aand 6B).

Figure 6A and B: Normal nasal mucosaVs. Nasal mucosa which appears pale in allergic rhinitis

The natural course of the disease leads to irreversible alterations such as turbinate hypertrophy, mucus or mucopurulent discharge that causes hyposmia, headache and infectious complications.

Furthermore, the chronic state of inflammation and hyper-reactivity is followed by complications such as sinusitis, otitis media and even asthma.

Features of Allergic Rhinitis in Affected Individuals

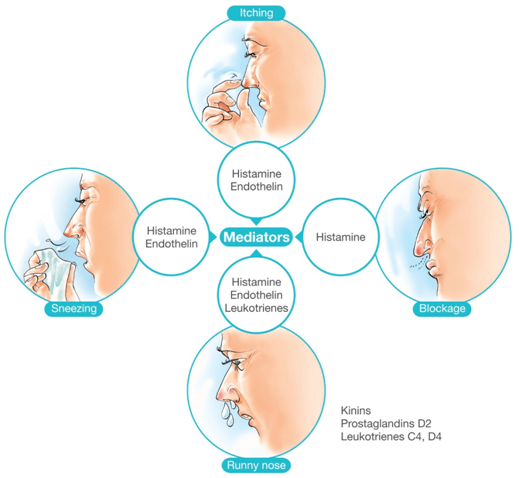

The plethora of molecular mechanisms that accompany allergic reaction in the nasal cavity is the reason why individuals with allergic rhinitis experience sneezing, itching, rhinorrhoea and blockage. Each of these symptoms is now known to be mediated by a specific mediator (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The role of mediators in symptom development in allergic rhinitis

While the onset of allergic rhinitis can occur in adulthood, most individuals develop symptoms by 20 years of age. The physiology of nasal cavity is such that the nasal vasculature is under the control of the sympathetic nervous system and its neurotransmitter, noradrenaline, is responsible for vasoconstriction and maintaining the airway patency. Any reduction in this sympathetic tone will result in vasodilation, indirectly leading to nasal congestion.

In addition to these neural effects, mediators generated from mast cells, eosinophils, etc., also have a direct effect on the nasal vasculature by again inducing nasal congestion and plasma exudation, which is a hallmark feature of allergic inflammation of the nasal cavity.

In allergic rhinitis, the symptoms could be seasonal or perennial, depending upon the presence of the offending allergen.

The following are the main features of allergic rhinitis (Figure 8):

- Nasal congestion: The mediators responsible are histamine, kinins, prostaglandins and leukotrienes. It is usually seen in both seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis.

- Postnasal drip: It is a common feature of allergic rhinitis and also the commonest cause of cough associated with this condition. A green-coloured mucopus implies infection while a yellow colour could be due to eosinophils and allergy.

- Sneezing: This, again, iscommon in allergic rhinitis and is mediated by histamine and endothelin.

- Rhinorrhoea: Described as runny nose, it is an important symptom of allergic rhinitis and is mediated by cholinergic neural reflexes in the nasal cavity.

- Itching in the nose and ears: Caused by histamine and endothelin.

Figure 8:Features of allergic rhinitis

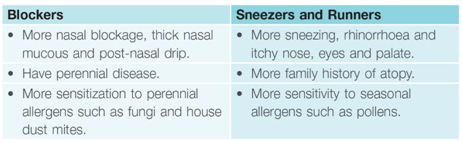

These are the basic cardinal features of an individual with allergic rhinitis. However, some individuals have predominant nasal congestion and some have a predominantly runny nose. Hence, such individuals were previously classified as ‘blockers’ and ‘sneezers and runners’, respectively. In a study done by Mir et al. who characterized these two clinical presentations in 114 adults with allergic rhinitis, the following features were observed (Table 1):

Table 1: Characteristics of ‘blockers’ and ‘sneezers and runners’

Identifying Allergic Rhinitis in Practice: Diagnosis

Allergic rhinitis often goes undetected because of patients underestimating the impact of the disease on their quality of life and also because of physicians failing to regularly screen patients during routine visits. A thorough history and physical examination are the cornerstones of the proper diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Although diagnostic investigations such as allergy testing are not routinely performed, they are important for confirming that underlying allergies are causing the rhinitis.

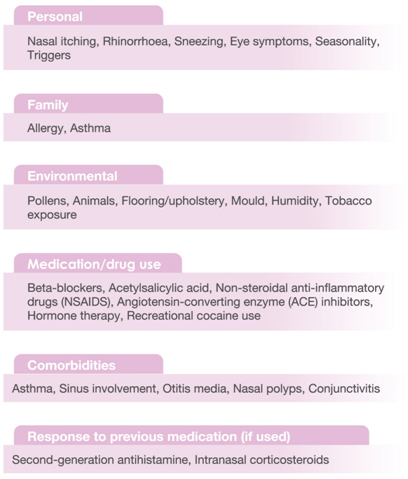

History

Patients will often describe the classic symptoms of allergic rhinitis while providing the history: nasal congestion, nasal itch, rhinorrhoea and sneezing. Allergic conjunctivitis is also frequently associated with allergic rhinitis and symptoms generally include redness, tearing and itching of the eyes.

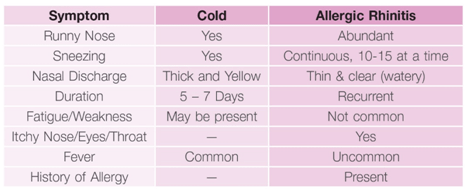

Patients may attribute such persistent nasal symptoms to ‘having a constant cold’ and, therefore, it is important to differentiate between the common cold and allergic rhinitis (Table 2).

Table 2: Differentiating between the common cold and allergic rhinitis

While taking the history, an evaluation of the patient’s home and work/school environments, any concomitant medication/drug use (such as beta-blockers, aspirin, cocaine, etc.) should be made to determine the potential triggers.

The history should also include a family history of any atopic diseases such as asthma or eczema, the impact of the symptoms on the quality of life as well as the presence of any comorbidity such as asthma, sleep apnoea, snoring, etc.

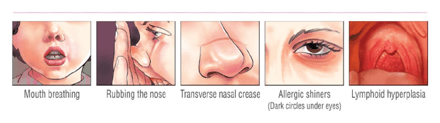

The following are the important components of history-taking with suspected allergic rhinitis (Table 3).

Table 3: Components of a complete history

The International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) has designed the following questionnaire to aid the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis (Table 4).

Table 4: Questions to aid the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis

This questionnaire will not produce a definitive diagnosis but may enable a physician to determine whether a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis should be investigated further.

History-taking should always be accompanied by a careful physical examination, which is described in the following sub-section.

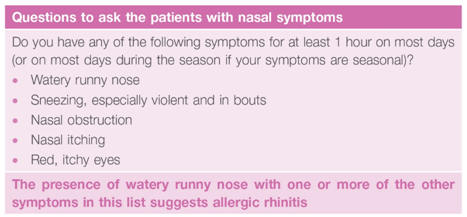

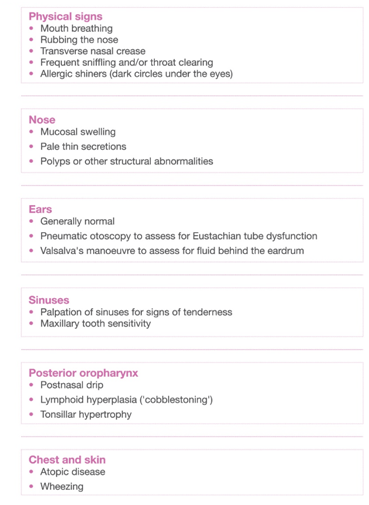

Physical Examination

The physical examination plays an important role in the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis and should include a thorough examination of the outward signs, nose, ears, sinuses and the back of the throat. The following table gives a glimpse of the various signs in allergic rhinitis (Table 5).

Table 5: Components of physical examination

Differential Diagnosis

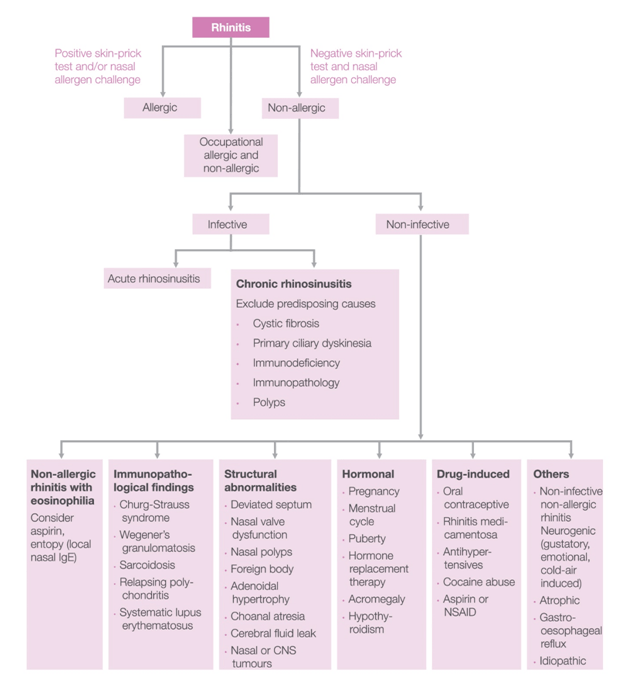

Allergic rhinitis is one of the sub-classifications of a broader disease category,namely, rhinitis. Rhinitis can be classified as allergic, non-allergic and occupational and, thus, can have many underlying causes.

About two-thirds of children and one-third of adults with rhinitis will present with allergic rhinitis; the remainder have other forms and some have idiopathic rhinitis.

Rarely does rhinitis present as a single-organ disease, and an appropriate diagnosis entails assessment of the upper and lower airways. A range of multi-system, non-allergic diseases can mimic rhinitis (for example, Churg-Strauss syndrome, Wegener’s granulomatosis and sarcoidosis) although these diseases are less common than allergic rhinitis.

The following flow-chart can help to diagnose as well as differentially diagnose allergic rhinitis (Figure 9):

Figure 9: Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of allergic rhinitis

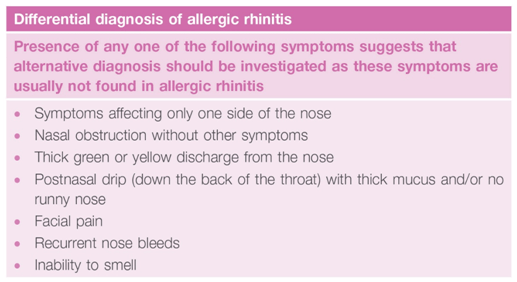

Presentation of the following symptoms can also help to differentially diagnose allergic rhinitis (Table 6).

Table 6: Questions to aid the differential diagnosis of allergic rhinitis

To confirm a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis, a physician can also employ certain diagnostic tests as discussed in the next subsection.

Diagnostic Tests

To confirm a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis, specific IgE reactivity to airborne allergens especially relevant to the patient’s history needs to recorded via either skin testing or by noting specific IgE in serum.

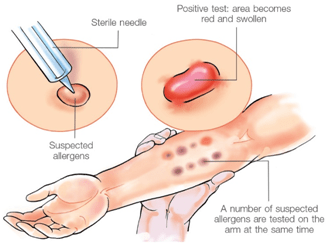

Skin Testing

Skin testing is an important diagnostic aid to identify the offending allergens. The principle behind this test is to introduce a tiny amount of allergen and gauge the response it evokes on the skin. There are various ways to introduce an allergen, including scratch, prick/puncture, intradermal and patch tests. Out of these,the skin-prick method is the one that is usually performed. It needs to be performed under supervision by a trained healthcare professional.

The following are some important pointers for skinprick testing (Figure 10):

- Skin testing is usually carried out on the inner forearm, but if the patient has bad eczema, the test can be performed on the back.

- Importantly, the test allergens selected should be in accordance with the patient’s history. Blanket allergy testing can lead to false-positive results.

- As few as 3 or 4 allergens or up to 25 allergens can be tested.

- The arm is coded with a marker pen for the allergens to be tested.

- A drop of the allergen (extract) solution is placed as per the relevant name or number.

- Then, through the drop, the skin is pricked by using the tip of a lancet — this can feel a little uncomfortable but should not be painful.

- A positive and a negative control are also used; the positive control will cause an allergic reaction in all people(for example, histamine) and the negative control should not cause any allergic reaction (for example saline).

- The patient needs to avoid taking antihistamines and certain other medications for 48 hours before the test.

Figure 10: Skin prick test

The test is considered positive if an immediate hypersensitivity develops (in the form of a wheal and flare reaction) within 15 minutes of introducing the allergen and if the wheal is of 3 mm or more in diameter (Figure 11).

Figure 11: A wheal and flare reactionin the skin prick test

Although a helpful diagnostic aid, there are certain disadvantages associated with skintesting. There could be false-positive or false-negative reactions, which mean that positive reactions to specific allergens in skin tests do not always have a direct correlation with the actual reactions in the nasal cavity. Furthermore, the test results can be influenced by some drugs (such as antihistamines), or the patients’ age and the test sites. If a patient has dermatological problems,the skin test can be difficult to perform. Also, there are no standardized criteria for positivity and, hence, they differ from clinic to clinic.

Despite these drawbacks, skin testing is regarded as the most important diagnostic method.

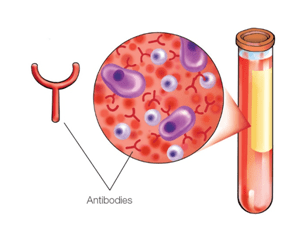

Serum Specific IgE Level

Serum specific IgE is measured by the radioallergosorbent test (RAST). This was the first method to detect serum-specific IgE but has not been popular because it requires a radioactive isotope and expensive equipment, and also because this test cannot detect multiple antibodies simultaneously.

Hence, the other widely used method is the multiple allergen simultaneous test (MAST). The MAST uses a photo reagent instead of a radioactive isotope, does not require expensive equipment and can detect multiple allergens simultaneously. This test is not affected by drugs such as antihistamines, is less invasive and can be used in patients with dermatological conditions. However, MAST has low sensitivity as compared to the skin-prick test.

However,it isimportant to note that all IgE tests must be interpreted with caution, keeping in mind the patient’s history.

Practical Treatment Strategies

Allergic rhinitis is a chronic disease that varies in severity from patient to patient. Hence, before the pharmacotherapy is initiated, it is essential that the severity and the pattern of allergic rhinitis are mapped for each and every patient. The following subsection describes the classification strategies employed before treating allergic rhinitis. Once the severity and impact of allergic rhinitis is understood,the treatment can be modified as per the requirements of the patient.

Classifying the Severity of Allergic Rhinitis

Traditionally, allergic rhinitis has been categorized as seasonal or perennial depending on the occurrence of symptoms. However, one limitation of this classification system was its oversimplification and not many patients fit into this classification scheme. For example, some allergic triggers, such as pollens, may be seasonal in cooler climates, but perennial in warmer climates. Also, patients with multiple ‘seasonal’ allergies may have symptoms throughout the year.

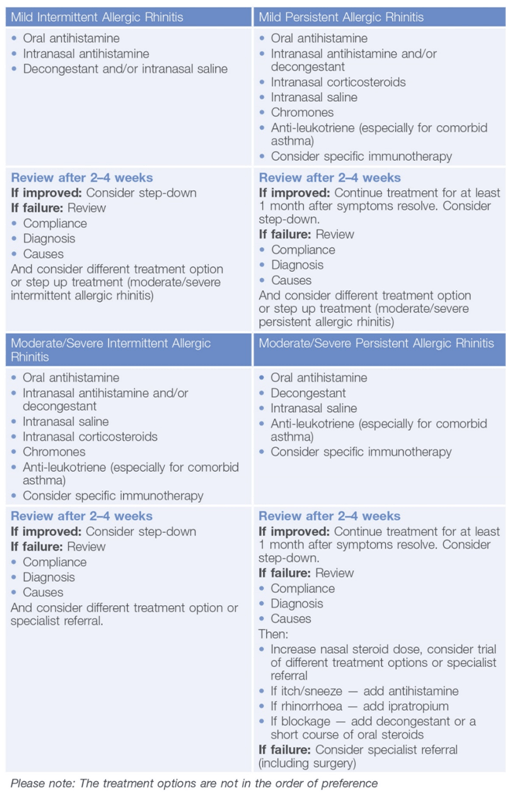

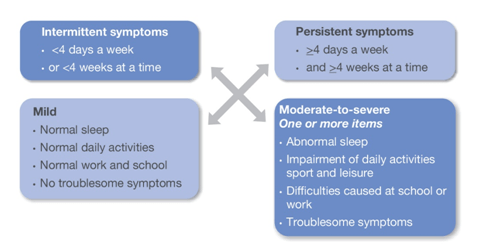

Hence, in 2008,the ARIA guidelines proposed a new classification system based on the frequency of symptoms and their impact on the patient’s quality of life(Figure 12).

Figure 12: Classification of allergic rhinitis according to ARIA

Once the patient is assessed for the frequency of symptoms and their impact on the quality of life, appropriate

pharmacotherapy can be initiated.

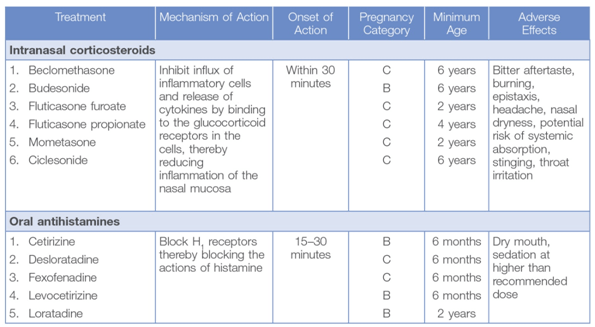

Drugs Used For Treating Allergic Rhinitis

The goals of the treatment of allergic rhinitis are as below:

- No troublesome symptoms

- Performance of near-normal daily activities, work/school and leisure

- No sleep impairment

- Minimal or no sideeffects of treatment

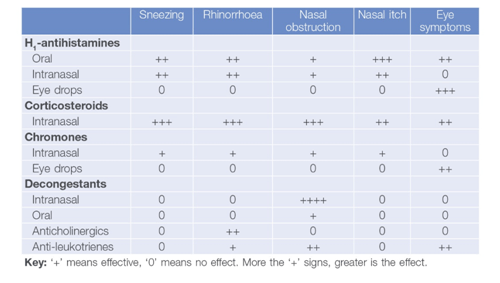

Table 7 gives a list of the various drugs used for the treatment of allergic rhinitis and their effects on the various symptoms of allergic rhinitis.

Table 7: Drugs used in the treatment of allergic rhinitis and their effects on the individual symptoms of allergic rhinitis

These drugs can be used in permutations and combinations as per the classification of allergic rhinitis in a patient

(Table 8).

A nasal route of administration is preferred for treating allergic rhinitis as it directly targets the nasal mucosa and gives rapid relief from symptoms (only in case of intranasal antihistamines) and that too at a low medication dose. Since inflammation is the mainstay of allergic rhinitis, intranasal corticosteroids (INCS) are the gold standard therapy because of their optimal effectiveness for treating allergic inflammation. They act by decreasing the influx of inflammatory cells and inhibiting the release of cytokines, thereby reducing inflammation of the nasal mucosa. Their onset of action is 30 minutes, although peak effect may take several hours to days, with maximum effectiveness usually noted after two to four weeks of use.Many studies have demonstrated that nasal corticosteroids are more effective than oral and intranasal antihistamines in the treatment of allergic rhinitis.

Table 8: Treatment options according to the classification of allergic rhinitis

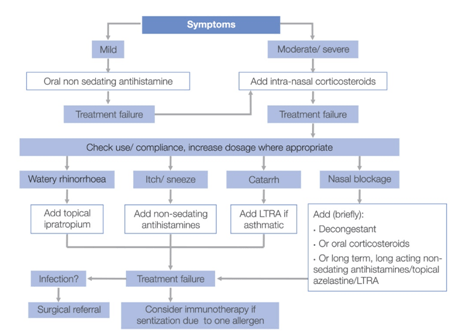

For better clarity regarding the table described above, the following treatment algorithm could be useful (Figure 13).

Figure 13: Treatment algorithm for allergic rhinitis

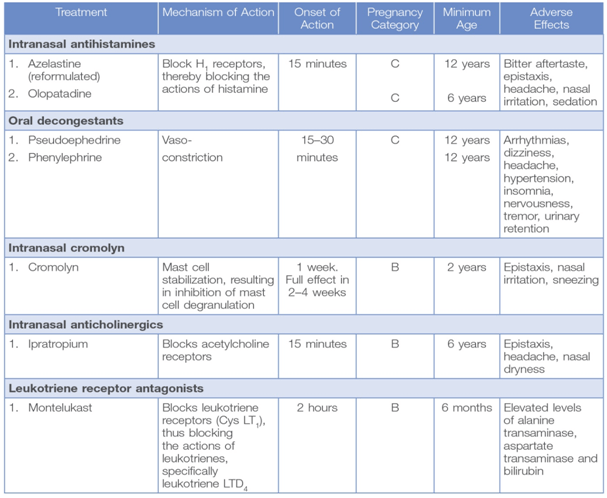

The details of the individual molecules used to treat allergic rhinitis are as given in Table 9.

Table 9: Drugs used for treating allergic rhinitis

Other than the drugs mentioned in Table 9, combination therapy (for example a combination of fluticasone furoate and azelastine or montelukast and levocetirizine) can be an option for patients with allergic rhinitis.

Rationale for Combination of Oral Anti-Histamines and Anti-Leukotrienes

Oral formulations are available as combination of leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast with a second generation antihistamine such as levocetirizine or fexofenadine. Both anti-histamines and leukotriene-receptor antagonists have anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory properties, including effects on mediator release and chemoattraction of inflammatory cells. These findings suggest that administering anti-histamine and leukotriene modifiers together may result in an amplified effect in the treatment of AR. There have been studies which showed that combination of anti-leukotriene like montelukast and antihistamine (loratadine, levocetirizine, fexofenadine) results in the reduction of nasal symptoms as well as improved quality of life of patients suffering from PAR as well SAR. The combination has been shown to be superior to either drug alone.

Rationale for Combination of Intranasal Anti-Histamines and Corticosteroids

Intranasal formulations include combination of a corticosteroid (such as fluticasone propionate, fluticasone furoate) with an antihistamine (azelastine). As antihistamines are fast-acting, instant relief from the symptoms can be achieved while the corticosteroid acts on the underlying inflammatory component thereby controlling the progression of the disease. The combination of an antihistamine and a corticosteroid helps in achieving optimum symptom control as both the late phase and the early phase symptoms of the disease would be attenuated. Many studies have shown the combination of intranasal corticosteroids and antihistamines is superior to the respective monotherapies.

Since allergic rhinitis is a chronic disease the treatment should be continued till the symptoms are under control. Once symptom control is achieved, treatment can then be stepped down to the minimum effective dose or no treatment. However, allergic rhinitis is a variable disease and requires a step up in the treatment once symptoms restart like after coming in contact with the allergens. Patients having seasonal symptoms may need a prophylactic therapy.

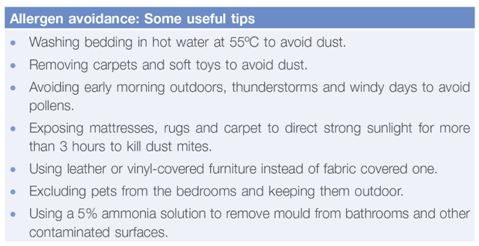

However, a successful therapeutic approach should not only involve pharmacotherapy but also non-pharmacological management such as patienteducation and allergen avoidance.

Treating Allergic Rhinitis beyond Drugs

Treating allergic rhinitis involves notonly pharmacotherapy but also patienteducation and allergen avoidance as these components too play an important role in disease control.

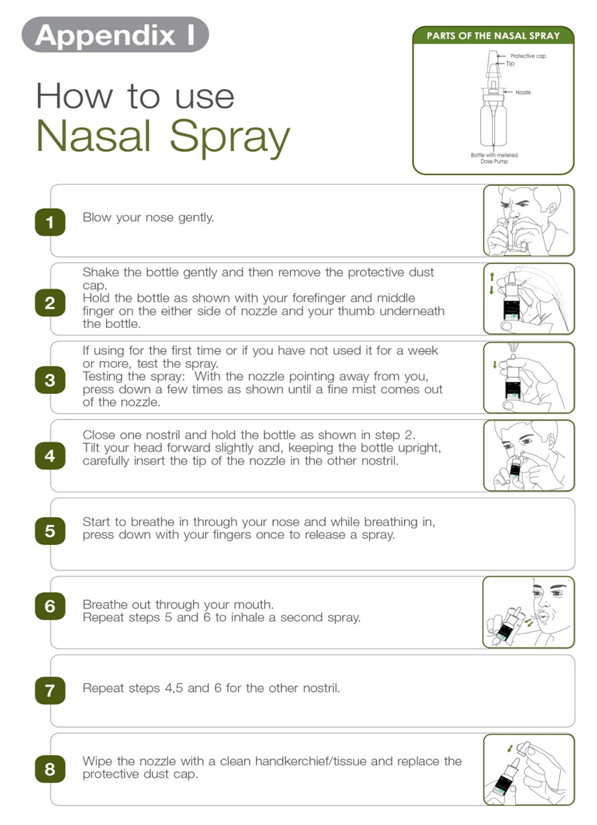

Patients should be educated about the allergic nature of the disease, the likelihood of disease progression, and the need for treatment. Patients should also be informed about the triggers that could aggravate the symptoms and the importance of avoiding them. The importance of using nasal sprays for the treatment of allergic rhinitis should also be stressed on along with a demonstration on using a nasal spray correctly.

Complete allergen avoidance, though not practically feasible, should be advised to the patients. Many patients with allergic rhinitis have nasal hyperreactivity to non-specific stimuli such as changes in temperature, air conditioning, pollution and cigarette smoke. Hence, patients with allergic rhinitis should avoid these stimuli.

Nasal irrigation or saline douching has been shown to be useful and may allow a reduction in pharmacotherapy, especially in children and pregnant women. Nasal irrigation using a ‘neti pot’ (a pot used for a yogic technique) is considered superior to saline nasal sprays. Patients should also be asked to avoid self-medication.

Table 10 gives some useful tips to avoid allergens (these can be shared with the patients).

Table 10: Tips to avoid allergens

Managing Rhinitis in Pregnant Women

Pregnancy-induced rhinitis can occur in 20% of women and is often self-limiting. Since most medications cross the placenta, the physician needs to look at the benefits versus the risk to the foetus.

Some general rules are as follows:

- Avoid decongestants.

- Regular nasal irrigation or douching may be useful.

- Beclomethasone, fluticasone and budesonide nasal sprays have good safety profiles and are widely used in pregnant asthmatic women.

- Chlorpheniramine, loratadine and cetirizine are likely to be safe, but decongestants should be avoided.

- Chromones(as eye drops and nasal sprays) are the safest drugs recommended in the first 3 months of pregnancy although they require multiple daily doses.

- Women who get pregnant while on immunotherapy should continue treatment. However, initiation and updosing phases of immunotherapy are contraindicated in pregnancy.

Allergic Rhinitis in Children: A Special Focus

Allergic rhinitis is very common amongst children; about two-thirds of children and a third of adults with rhinitis have allergic rhinitis. Data from various epidemiological studies suggest that up to 40% of children suffer from allergic rhinitis. The disease can have a profound effect on the daily life of a child, making him or her irritable, sad, sleep-deprived and limiting his or her activities at school and home. The symptoms of allergic rhinitis can cause severe distraction during class hours, resulting in decreased productivity. In the longer term, allergic rhinitis can cause learning impairment in children due to day-time fatigue and its impact on cognition. Hence, it is important to explain all the treatment options to the parents.

Of particular interest is the natural history of allergic rhinitis in children. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is a more common in teenagers and young adults, while perennial allergic rhinitis is more common in primary and pre-school children. At the primary and preschool ages, nasal blockage is a more prominent symptom,but it can frequently escape detection.

The first-line treatment should include a once-daily, long-acting antihistamine or intranasal corticosteroids given continuously or prophylactically for symptoms of rhinorrhoea, sneezing, rash or conjunctivitis or nasal obstruction.

Intranasal Corticosteroids

- Useful for nasal congestion and obstruction.

- Preparations with low systemic bioavailability should be used.

- Intermittent use can be beneficial.

Second-Line Treatments

- For nasal congestion, the combination of corticosteroids, nasal drops and a topical decongestant can be useful for a short-term use only (less than 14 days).

- In severe seasonal allergic rhinitis, particularly before exams or other important events, a short course of oral steroids (25 mg/day for 5–7 days) can be effective in children (2 mg/kg/day up to 25 mg).

- Injectable depot steroid preparations are not recommended.

- For refractory rhinorrhoea, ipratropium bromide 0.03% can be tried.

- In seasonal allergic rhinitis, saline irrigation can be useful.

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists can be useful in comorbid asthma.

- Immunotherapy is effective and sublingual immunotherapy is available for children.

Patients who show persistent failure to respond to therapy or whose symptoms are suggestive of other conditions should be referred to a specialist.

Management beyond Allergic Rhinitis: Comorbidities

Allergic rhinitis is closely linked to other inflammatory diseases affecting the respiratory mucous membranes such as asthma, rhinosinusitis and allergic conjunctivitis

Asthma

Epidemiological evidence has repeatedly shown the co-existence of rhinitis and asthma. Both allergic and non-allergic rhinitis are risk factors for the development of asthma. Up to 19–38% of allergic rhinitis patients can have asthma. In fact, childhood allergic rhinitis was associated with a threefold increased risk of childhood asthma. In India, 75% of asthmatic children have concomitant rhinitis symptoms.

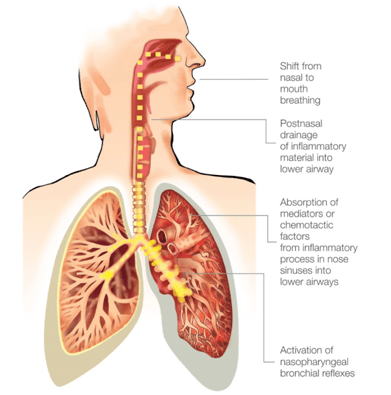

Figure 14: The pathological link between upper and lower airways

The link between asthma and allergic rhinitis is associated with the ‘one airway, one disease’ concept where the upper and lower airway is considered as a single morphological unit (Figure 18). The risk of the development and severity of asthma increases when a patient is sensitized to indoor allergen such as house dust, mites or cat dander. The prevalence of asthma further increases in moderate-to-severe allergic rhinitis patients sensitized to both indoor and outdoor allergens.

The management of comorbid asthma and allergic rhinitis is using a single treatment approach. Glucocorticosteroids are the most effective drugs for the treatment of rhinitis and asthma when administered topically in the nose and the bronchi. Another treatment option is montelukast, which is effective in both allergic rhinitis and asthma. Oral antihistamines are a first-line treatment in allergic rhinitis and, hence, they are neither recommended nor contraindicated in the treatment of asthma.

Allergic Conjunctivitis

This,again, is one of the most common accompanying diseases of allergic rhinitis, which is attributable to outdoor allergen such as pollens rather than indoor allergens. About 75% of allergic rhinitis patients complain of the symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis. Intranasal corticosteroids such as fluticasone furoate have been shown to suppress the nasal as well as ocular symptoms.

Chronic Rhinosinusitis

The role of allergy in sinus disease is still unclear. Many studies have suggested that allergic inflammation could affect acute or chronic rhinosinusitis. A similar inflammation is observed in the nose and sinuses of patients with allergic rhinitis. Patients with perennial allergic rhinitis are at a larger risk of developing sinusitis. Fungal elements are one of the causative agents of chronic rhinosinusitis. However, the benefit of treating allergic fungal rhinosinusitis with an antifungal agent such as amphotericin B is unclear. Even so,the addition of anti-allergic treatment is logical in the treatment of chronic sinus disease and concomitant allergy.

Nasal Polyps

Nasal polyps are considered as a chronic inflammatory disease of the sinonasal mucosa, being part of the spectrum of chronic sinus pathology. However, the role of allergy in the development of nasal polyps is still unclear. Certain intranasal corticosteroids such as mometasone have been approved to treat nasal polyps. If intranasal corticosteroids are unable to control nasal polyps, then alternate therapies such as polypectomyshould be considered.

Adenoid Hypertrophy

Sensitization to inhaled allergens can alter the immunological parameters of the adenoids though the exact role of allergy in adenoid hypertrophy is still unclear. Although there have been a few reports on the efficacy of antihistamines in allergic rhinitis patients with adenoid hypertrophy, intranasal corticosteroids are known to improve the symptoms of adenoid hypertrophy regardless of the presence of atopy.

Conclusion

Allergic rhinitis is a common chronic disorder whose prevalence continues to rise and is associated with a number of comorbidities and complications. It continues to have a significant impact on the quality of life and the social, professional and family life of the patient. Irrational treatment in the form of undertreatment, overtreatment and the use of inappropriate drugs compound the problem. Hence, physicians should be aware of the aetiology, pathophysiology, symptoms, signs and diseases related to allergic rhinitis in order to make a correct diagnosis and choose a proper treatment option for each patient.

How to Use Nasal Spray

References

- Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 and Update 2010

- J Allergy ClinImmunol 2008; 122:S1-84

- Pawankar RS et al. The Burden of Allergic Diseases. In: Pawankar RS et al., editors. World Allergy Organization (WAO) White Book on Allergy. UK: World Allergy Organization, 2011. pp 27–70

- Asia Pac Allergy 2012; 2:93–100

- Clin Applied Immunol Rev 2001; 207–216

- Lancet 2011; 378:2112–22

- Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2010; 2(2):65–76

- Shaikh WA, Saha R. Allergic Rhinitis. In: Shaikh WA, Principles and Practice of Tropical Allergy and Asthma.Mumbai: Vikas Medical Publishing, 2006. pp 293–319

- Supplement to The Journal of Family Practice 2011; 60; S5–S15

- J Allergy ClinImmunol 2001; 108:S45–53

- Allergy, Asthma and Clinical Immunology 2011; 7 (Suppl 1):S3

- Prim Care Respir J 2006; 15:20–34

- Allergy 2008; 63:981–989

- BMJ 2002;325:414

- ClinExp Allergy 2008; 38: 19–42

- Prim Care Resp J 2010; 19 (3):217–222

- Prim Care Resp J 2006; 15:58–70

- Am Fam Physician2010; 81 (12):1440–1446

- Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2002; 88 (Suppl):8–15

- J Allergy ClinImmunol 2007; 120:863–9

- Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 2009; 27:71–77

- PaediatrRespir Rev 2009; 10:63–68

- ClinExpImmunol. 2009; 158: 164 – 173

- Allergy Asthma ClinImmunol. 2008; 4: 125 - 129