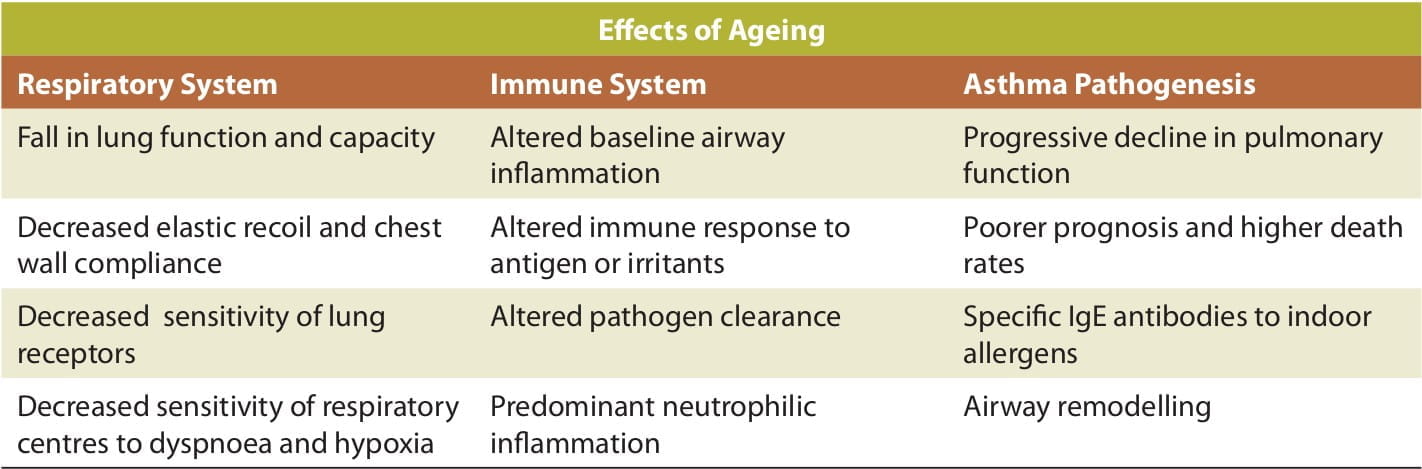

Ageing does play an essential role in asthma pathogenesis and also has an implication on its diagnosis and management in the elderly. The following figure explains the effects of ageing on the respiratory system, immune system as well its manifestation on the pathophysiology of asthma in the elderly:

Asthma and Elderly

Asthma and Elderly

Ageing and Asthma

Presentation of Asthma in the Elderly

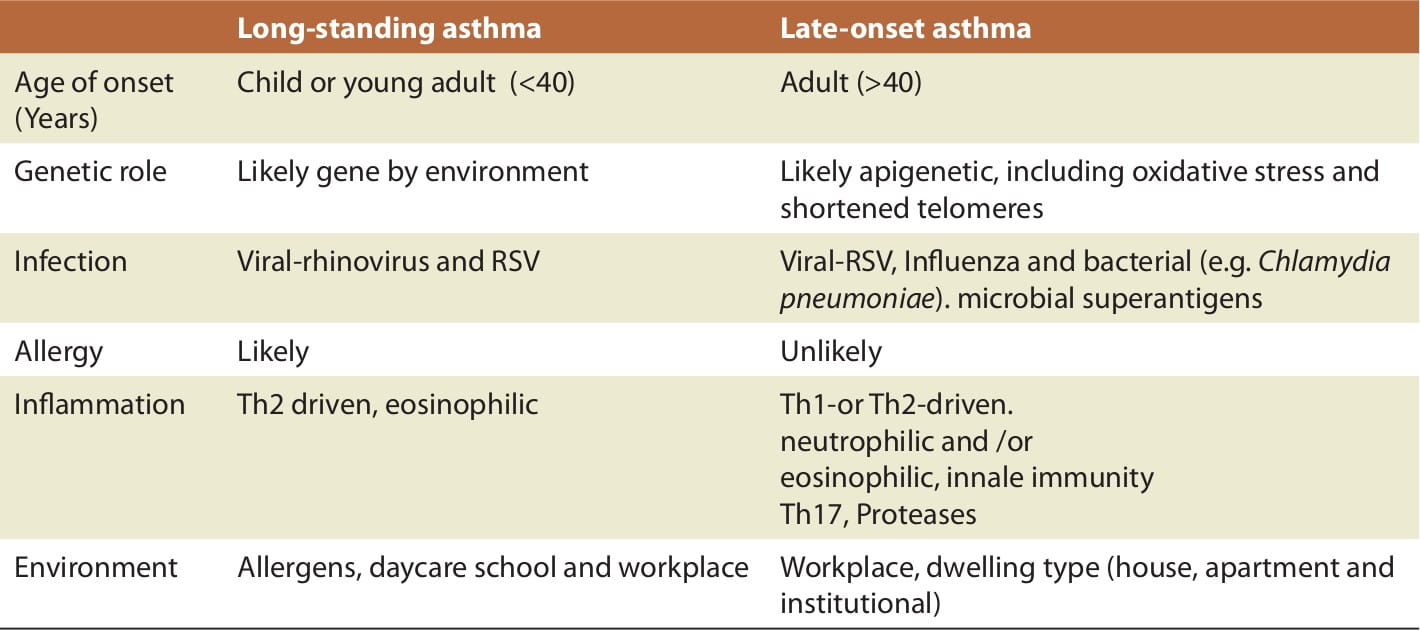

Despite increased morbidity and mortality in older patients with asthma, the pathogenesis in this age group is not well-characterized. Asthma in the elderly may result from the persistence of childhood asthma, the return in later life of childhood asthma that was quiescent in adulthood, or asthma that developed in later life (late-onset asthma). (Table 1).

As in childhood onset asthma, a family history of asthma is also a risk factor for late-onset asthma in the elderly, in addition to allergen sensitization. However, respiratory infections such as the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and Chlamydia pneumoniae may play a more important role than atopy in the development of such late-onset asthma (Table 1). Having a history of smoking is also an influential factor although it has been implicated more in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Table 1: Potential mechanisms for asthma phenotypes in the elderly

Asthma in children and adults is primarily a clinical diagnosis. However, symptoms that suggest asthma, such as wheeze and a sensation of bronchospasm, may be absent in older asthmatic patients. Furthermore, even when present, typical respiratory symptoms of wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough have poor predictive value in old age.

The symptomatology in elderly asthmatics is relatively non-specific because of the presence of co-morbidities. However the 'hallmark' of asthma remains the same across all ages, i.e., symptoms tend to be variable, intermittent, worse at night and provoked by triggers, including exertion, and eliciting these features remains at the core of diagnosing asthma in older people.

Diagnosis of Asthma in the Elderly

Under-diagnosis of asthma in the elderly remains a major issue and the reasons for this are multifactorial and include reduced perception of symptoms, misattribution of symptoms to other causes and underuse of objective testing such as spirometry. The diagnosis of asthma is made by determining the symptoms by examining the medical history and obtaining an objective assessment of the variable airflow obstruction.

History and Differential Diagnosis

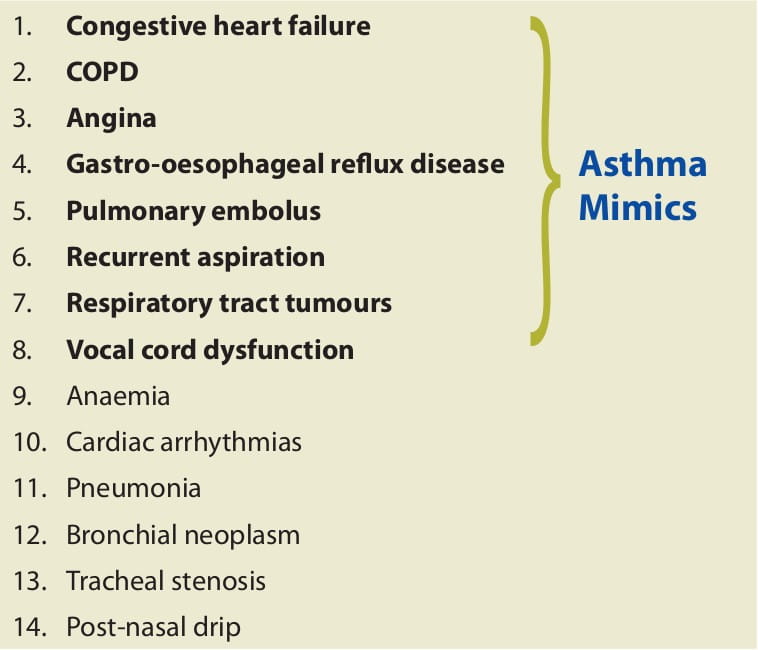

The typical symptoms of asthma such as dyspnoea, chest tightness, cough and wheezing are similar in both elderly and young patients. However, when considering the diagnosis of asthma in an older patient, there are a number of diseases that should be included in the differential diagnosis. But, it is important to rule out the conditions that mimic asthma. Hence, the following list of conditions can be considered for the differential diagnosis of asthma in older patients:

Table 2: Differential diagnosis of asthma in older patients

- It is vital to evaluate whether the elderly individual is a poor perceiver of symptoms by asking about any physical activity modifications secondary to the symptoms consistent with asthma.

- A careful medication history is required to identify any therapeutic agents, such as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, which may produce a cough that mimics asthma. Other examples include aspirin and beta-adrenergic blockers.

- The medical history should include both a family and patient history of previous allergic diseases, including eczema, allergic rhinitis, and drug and food allergies as a guide to allergic asthma.

- It is also important to consider the smoking history of the patient (not only pack/years of cigarette smoking but also passive exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) as well as biomass fuels and air pollution) since this might have induced co-existing COPD.

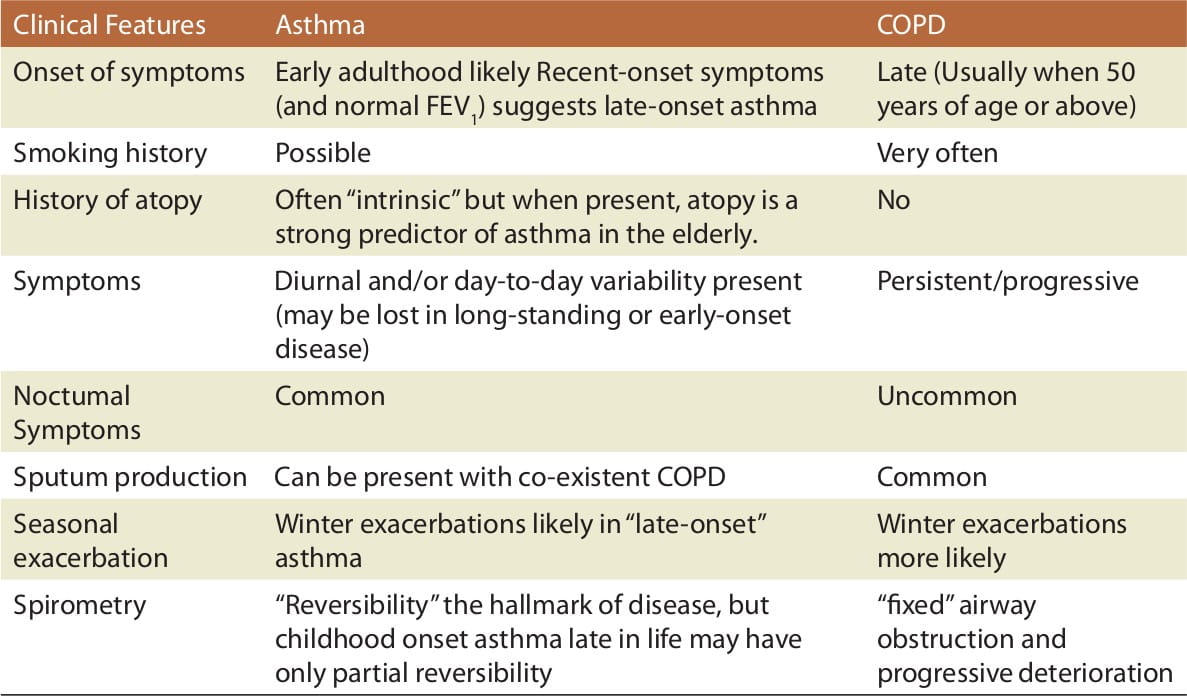

Distinguishing Asthma from COPD

Table 3: Clinical pointers to distinguish asthma from COPD

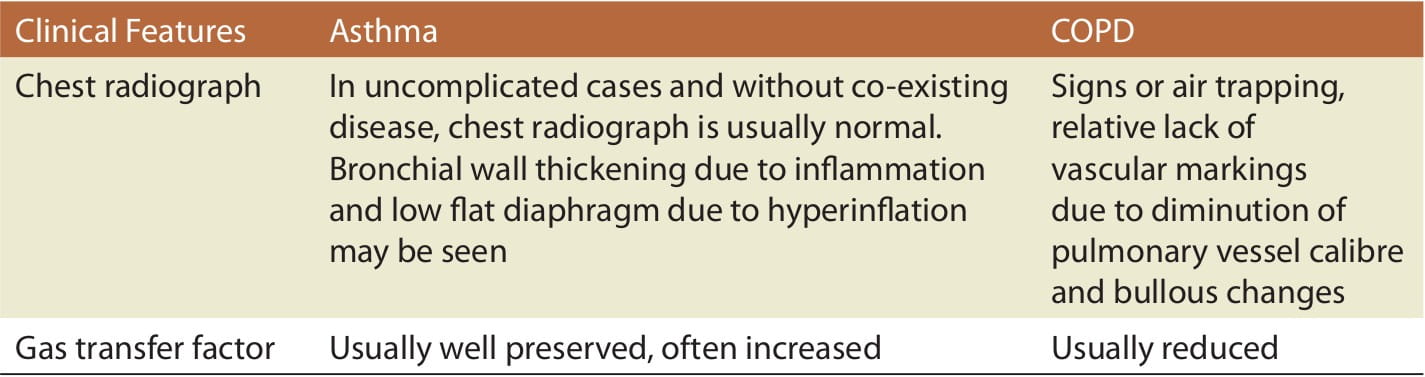

However, the diagnosis of these two distinct diseases is not always straightforward since many elderly individuals may present with an 'overlap syndrome'.

Table 4: Features of an overlap of asthma and COPD

Objective Measurements

It is important to evaluate the clinical symptoms of asthma by office spirometry, which measures the FEV1 and the FVC. If the spirometry results are consistent with airway obstruction, it is essential to perform the bronchodilator reversibility test; a 12% or 200 ml increase in the FEV1 values is suggestive of reversible obstructive airway disease.

Spirometry in the Elderly

There is a misperception that reliable spirometry measurements cannot be obtained from elderly individuals. Several studies have demonstrated that between 82% and 93% of elderly patients are able to perform good spirometry.

Ageing is associated with a decline in the FVC and FEV1 by 15-30 ml/year, and the decline in the FEV1 often exceeds the reduction in the FVC, resulting in a decline in the predicted values and lower limit of normal. Using a fixed cutoff value (<70%), as is recommended by Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease(GOLD), potentially results in overestimation and misclassification of obstructive lung disease in older adults.

Good quality testing from an elderly patient may require 20-30 minutes more than the time required for younger subjects. The minimum number of FVC manoeuvres needed to achieve consistent results is higher in older adults (up to 5-8 manoeuvres required). Older patients have difficulty in achieving end-of-test thresholds and using slow vital capacity manoeuvres or the measurement of FEV1/FEV6 (forced expiratory volume in 6 seconds) to detect airflow obstruction.

- In patients who are unable to perform spirometry, the patient should be asked to undergo body plethysmography; this allows the patients to breathe more 'normally'.

- To distinguish between asthma and COPD, formal spirometry, lung volumes and diffusion capacity should be performed; in patients with COPD, the diffusion capacity is reduced whereas in asthma it remains normal or is elevated.

- It is important to note when performing bronchodilator reversibility that in the elderly, there may be decreased reversibility due to age-related decline in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system functions as well as permanent airway changes due to fibrosis, tracheal instability or bronchiectasis.

- A ratio of FEV1/FVC <0.7 or FEV1 <80% predicted suggests obstructive lung disease but does not distinguish between asthma and COPD.

- Measuring the peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) variability, especially the diurnal variability of ≥20% (ideally at least 60 l/minute), for 3 days in 2 weeks, over a period of time, may be a useful option in the absence of office spirometry.

- It is important to note that age-related decrease in the diurnal variability does not exclude the diagnosis of asthma.

Alternative methods for examining significant airflow reversibility to the PEFR or FEV1:

- Inhalation of a short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA), e.g. with metered dose inhaler (MDI) salbutamol 400 mcg with spacer or nebulizer 2.5 mg; and,

- Corticosteroid trial with prednisolone 30 mg/day for 14 days.

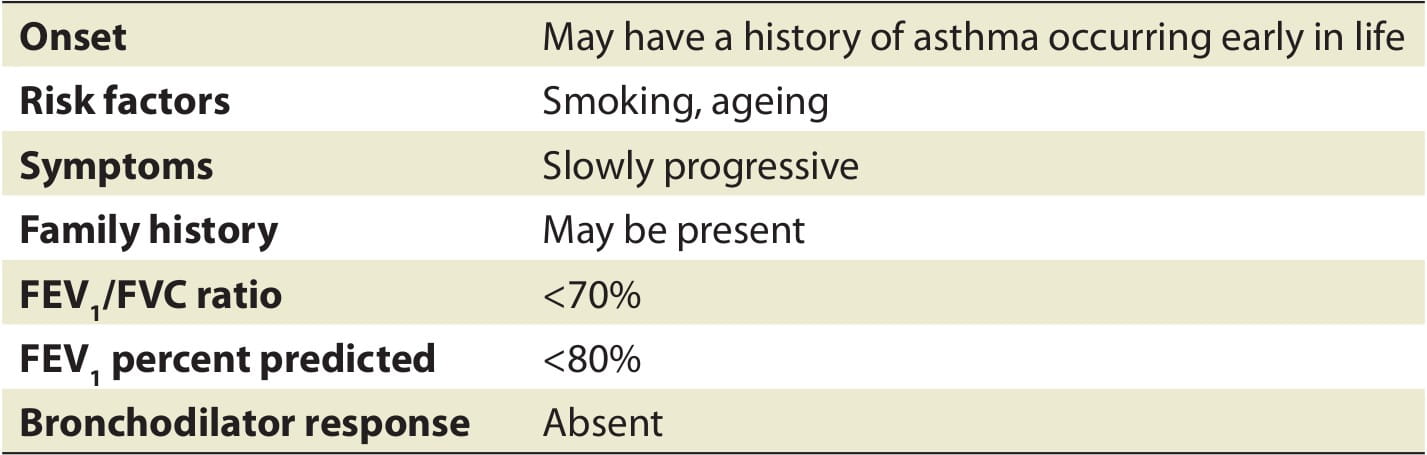

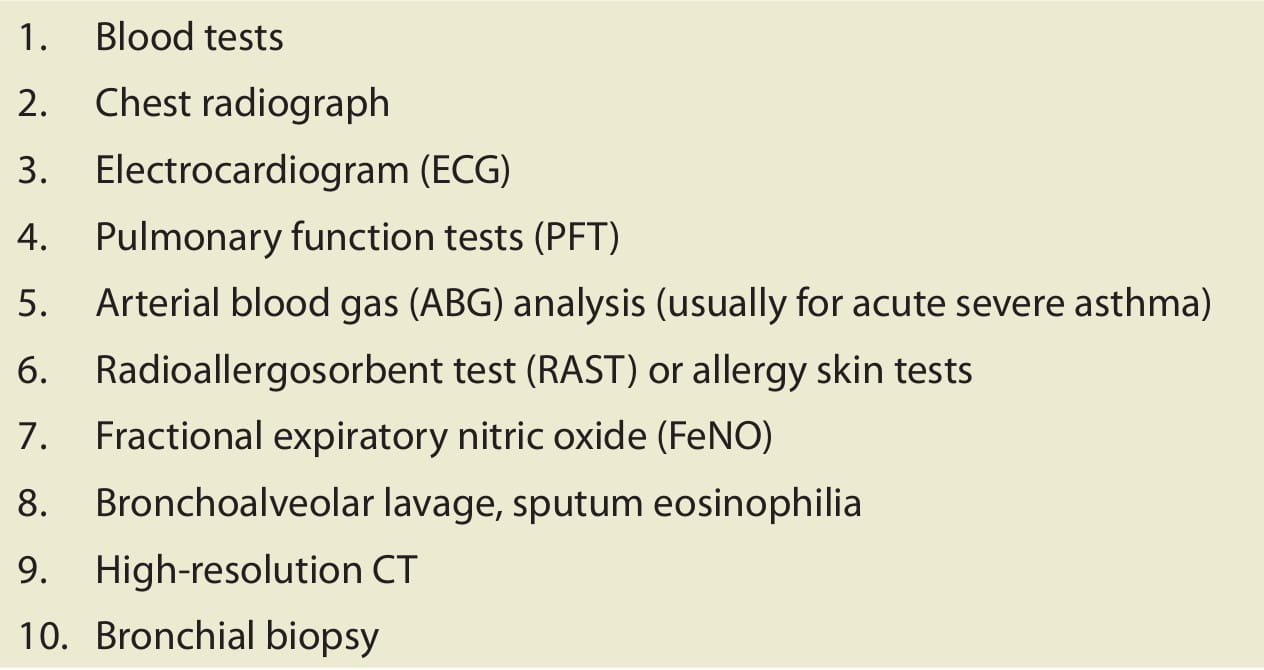

Other Investigations

Investigations in suspected asthma at first presentation in older people are important to differentiate asthma from the various diseases that may present with wheeze or breathlessness. Investigations are also important in asthma in following the course of the disease, response to treatment and in the management of acute severe attacks.

Table 5: List of other investigations in asthma

Management of Asthma in the Elderly

Generally speaking, the principles of asthma management in the elderly remain the same as in the younger population, with special considerations for education and medication use. The goals of management revolve around the same components of asthma management as in the younger population, namely, assessment and monitoring, education, control of triggers and pharmacotherapy.

Assessment and Monitoring

At the initial visit, the patient's asthma should be classified either according to the severity or the level of control as per the asthma guidelines, as is done in the younger adults.

- All patients with asthma should be seen every 1-6 months to assess the medical control of their disease.

- If a change in medication has been made, patients should be seen sooner, i.e., within 2-6 weeks.

- Spirometry and a PEFR meter are recommended for the assessment and monitoring of asthma.

- When using PEF meters, a personal best should be established and this should be ideally obtained in the middle to late part of the day.

Control of Triggers

When performing the initial assessment, it is critical to ask patients what triggers their asthma as these exposures may be modified. Common triggers include aeroallergens, infections (commonly viruses and sometimes bacteria), irritants and psychosocial factors, including depression and social isolation, and allergen avoidance measures should be applied. Since viral and pneumococcal infections are frequent risk factors for asthma as well asthma exacerbations in the elderly, it may be beneficial to administer the pneumococcal vaccination more frequently than every 5-10 years because, with ageing, IgG opsonophagocytic activity and response to polysaccharide vaccination diminish.

Pharmacotherapy

The principles of pharmacologic treatment are similar for all ages. The medications used to treat older patients with asthma are not significantly different from those used in younger patients. However, there are several important considerations when prescribing these medications in older patients, including dosage adjustments for metabolic rates, drug interaction adverse effects, costs and delivery.

Since it is highly likely that asthma and COPD converge in the elderly individuals, the pharmacological management should take this fact into account while treating this population. Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) have been a cornerstone of asthma treatment and, in combination with long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs), have proven their efficacy in COPD. Additionally, patients with asthma and COPD should be advised to stop smoking.

ICS in the Elderly

Corticosteroid therapy is the most effective form of anti-inflammatory medication for asthma; however, whether they inhibit the development of long-term structural changes in the airways is not known. To determine if ICS will have clinical benefit, patients may be given a 2-week trial of oral corticosteroids at a dose of 0.3-0.5 mg/kg (a dose lower than used in younger patients), after which the lung function test can be repeated to determine if the airways hyper-responsiveness is reversible.

- Patients should be prescribed an ICS with the lowest oral bioavailability and also be given the lowest dose of ICS to control their disease, i.e., <1,600 mcg/day of budesonide or 1,000 mcg/day of fluticasone.

- Patients on corticosteroids should be closely followed for osteoporosis and cataract, and to lessen the effects of corticosteroids on bone resorption, patients should be encouraged to exercise, avoid excess alcohol intake and take daily supplemental calcium with vitamin D.

- Theophylline use in the elderly should be limited; if unavoidable, then it is critical to use the drug at a lowest possible dose and aim for a range of 8 to 12 mcg/ml while monitoring the serum levels.

- Beta-agonists must be used cautiously in patients with heart disease and hypertension be- cause an overdose may cause life-threatening arrhythmias and hypokalaemia.

- Combining non-potassium-sparing diuretics (e.g., thiazides) and beta2-agonists may cause significant hypokalaemia and hypomagnesaemia, increasing the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

- An annual influenza and pneumococcal vaccine is recommended in all elderly patients 65 years of age or older, immunocompromised patients, and in patients with any chronic respiratory condition, including asthma.

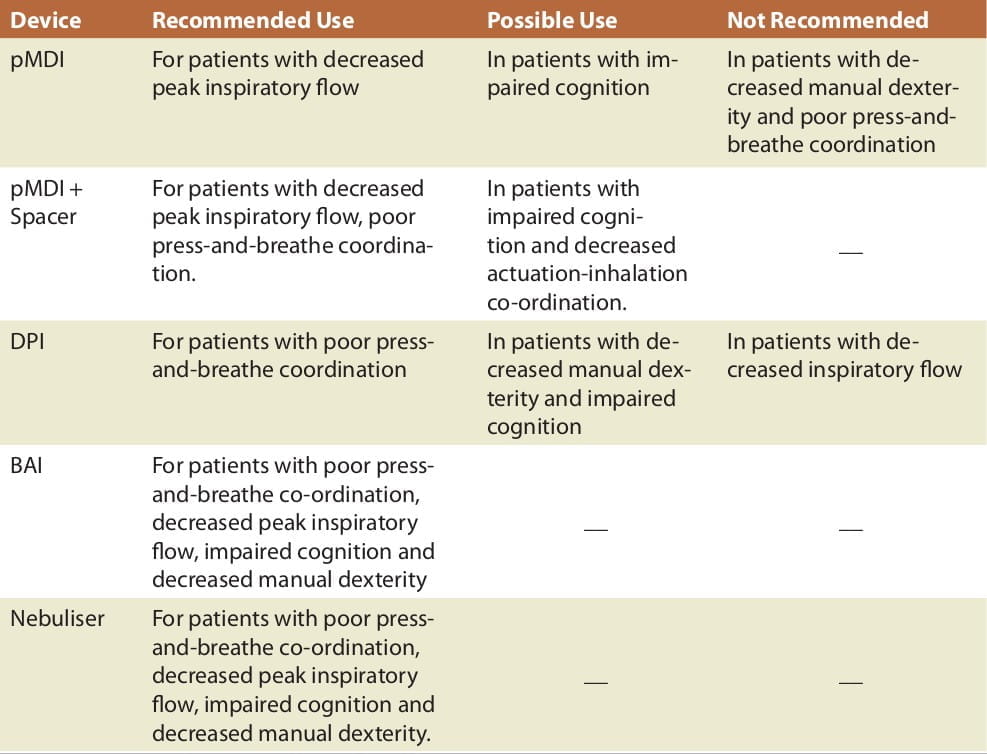

Inhalational Device Selection in the Elderly

Drug delivery by the inhaled route offers the best efficacy-to-safety ratio for many asthma therapies. However, an ineffective inhalation technique remains a substantial problem that contributes to poor symptom control. The error rate increases with both age and the extent of airflow obstruction. It has been reported that up to 82% of the elderly (older than 70 years) patients do not have an adequate pressurized MDI (pMDI) technique.

Older people with asthma can acquire and retain an appropriate technique after specific instructions, but these instructions need to be repeated and reinforced to ensure continuous good inhaler technique. Nebulized treatment can be replaced by the more efficient pressurized inhaler devices or, if not, then home nebulization can be recommended for daily use.

Specific factors leading to impaired inhaler technique in older people are learning difficulties from impaired cognitive function, impaired vision and fine motor skills and decreased generation of inspiratory flow. The following chart may be considered when selecting an inhalation device for the elderly (Table 6).

Table 6: Device selection for elderly asthmatics

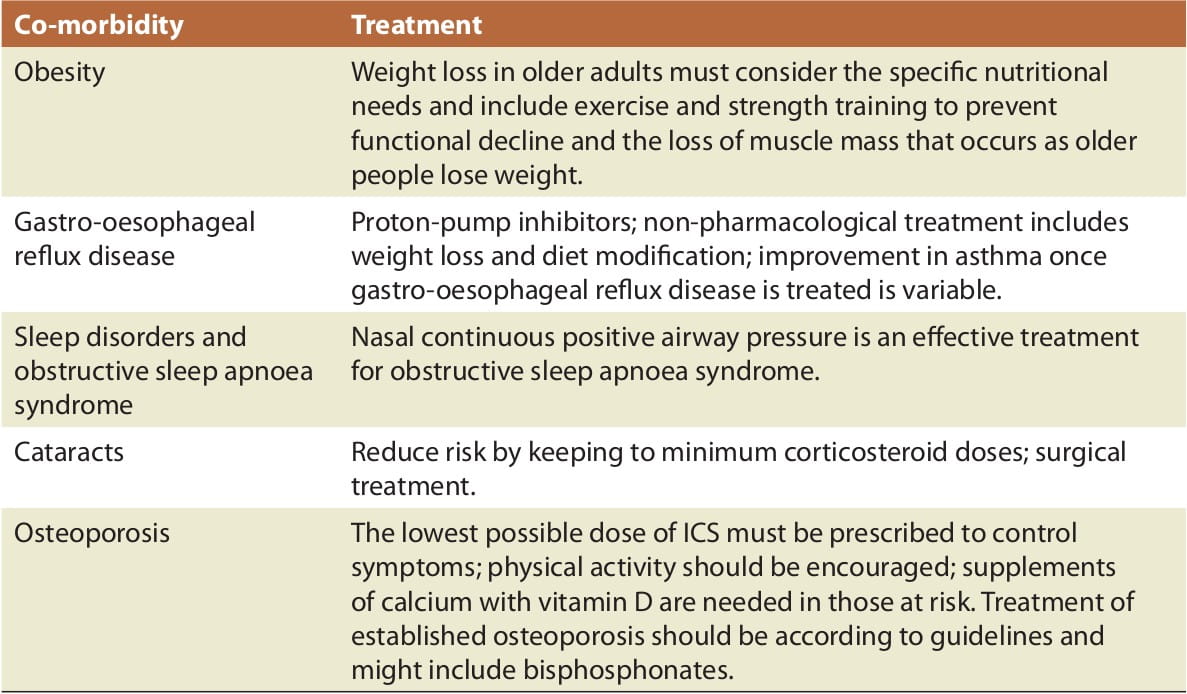

Managing Co-Morbidities in Elderly Asthmatics

The prevalence of co-morbidity from chronic disease increases with age. More than 50% of older people, aged 65 years or more, have at least three co-morbidities and a substantial portion have five or more, which are often unrecognized and untreated. Co-morbidity both compounds and confounds the management of asthma in older adults. Drug interactions and polypharmacy are important complications that accompany co-morbidity and ageing. Some of the common co-morbid disorders that complicate asthma and ageing are shown in the following table.

Table 7: Co-morbidities and that complicate asthma and ageing and their management

Other than the above-mentioned co-morbidities, it is also essential to manage others such as psychiatric co-morbidities (depression, panic attacks and general anxiety) as well as cardiovascular co-morbidities, all of which complicate asthma management.

Non-asthma drugs that may affect asthma:

- Beta-blockers

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)

- Non-potassium-sparing diuretics

- Cholinergic agents

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

Management of Acute Asthma in the Elderly

The management of acute severe asthma is no different in the elderly than in the young, but co-existing diseases and medications can make diagnosis and management very challenging, and complications more likely. Objective measures of disease severity are particularly important in the management of acute asthma in the elderly. Older asthmatics patients often have an impaired perception of acute bronchoconstriction; doctors tend to underestimate the severity of their symptoms and older patients take, on average, three times as long to present to a hospital, compared with younger patients.

Healthcare professionals need to make sure elderly patients understand how to monitor symptoms and identify signs (such as awakening at night due to asthma; an increased need for inhaled beta2-agonists to relieve symptoms or diminished response to inhaled beta2-agonists) or changes in the PEFR (if PEFR monitoring is used) that indicate their asthma is worsening.

Each patient should be given a management plan (in the form of a printed handout) that includes clear information on what to do and this action plan should also take into account the co-morbidities that the patient may suffer from.

For emergency care, hospital management and intensive care:

- Accurate diagnosis is important.

- Repeated doses of aerosolized beta2-agonists every 20-30 minutes during the first hour, with a close watch on possible adverse events, is safe in most elderly persons with asthma.

- Patients who demonstrate hypoxaemia (PaO2 of less than 60 torr) should receive supplemental oxygen.

- Immediate administration of systemic corticosteroids (intravenous or by mouth) should be considered in patients with severe exacerbations who fail to improve after the initial dose of beta2-agonists, in patients who develop an exacerbation while already taking oral corticosteroids, and in patients who have a history of frequent refractory episodes that require corticosteroids for resolution.

- Ipratropium bromide is a therapy to consider in patients with coexistent COPD, and to be continued for those who have been taking the drug on a regular basis.

- Theophylline should be avoided in the initial (e.g., first 4 hours) emergency treatment of severe exacerbations in the elderly because of the uncertain benefits and the increased risk of toxicity and cardiac arrhythmias.

- Antibiotics are not recommended as routine therapy for asthma exacerbations. However, some elderly patients with asthma and co-existing COPD may benefit from a course of antibiotic therapy, especially if the exacerbation is characterized by an increase in sputum volume and viscosity.

Patient Education and Self-Management in Elderly Asthmatics

Good communication and rapport between healthcare professionals and the patient has long been recognized as crucial to asthma management. This entails an individualized approach, tailored to each patient's age, level of education, wishes for autonomy and social and psychological status, to educate patients and/or their caregivers to take charge of their disease. Adherence can be a complex issue in older people with chronic respiratory disease, which can also be improved by applying patient education and self-management strategies.

Components of Patient Education and Self-Management for Elderly Asthmatic Patients

- Education of the patient's family and/or caregiver

- Individualized written action plan

- Periodic review

Asthma education in elderly patients centres on several key issues such as the need for assistance with medication administration, assessment of inhaler technique, cognitive and/ or physical impairment, etc.

- Placebo inhalers that do not contain active medication can be used to teach and observe the patient's inhaler technique.

- The usual components of asthma education, such as what is asthma, how to recognize worsening, what steps to take, etc., should be discussed at the initial visit and needs to be reviewed at follow-up visits.

- Asthma action plans are helpful, especially when given in the form of a handout (in a large font size).

- Building of a successful partnership by discussing the goals of asthma treatment with the patient as well as the caregiver; also, issues regarding non-compliance or lack of under- standing should be addressed.

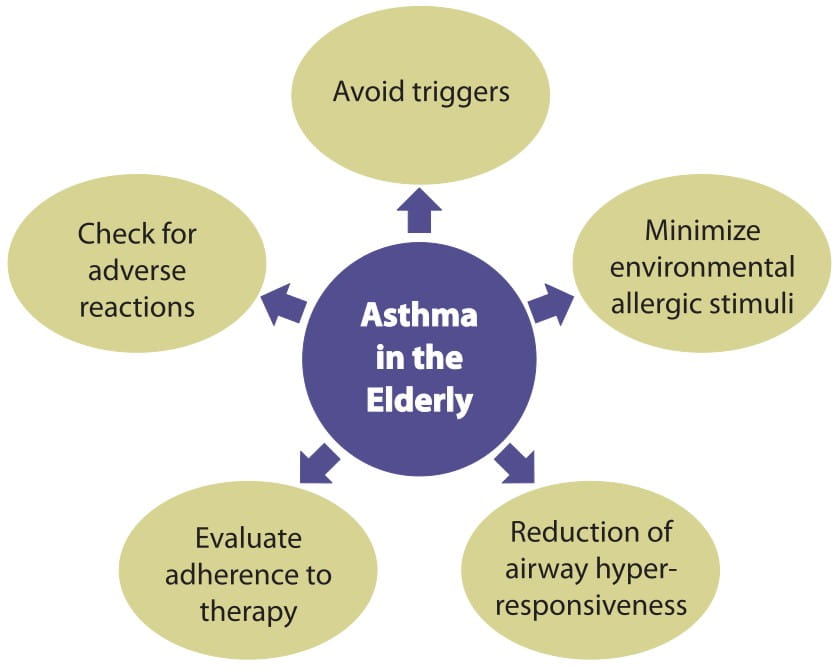

Reflections on the Management of Asthma in the Elderly

It has been suggested that a multidimensional strategy for the management of asthma in older people might be appropriate

This approach allows for personalized interventions that can be applied to manage the biological, clinical, functional and behavioural characteristics of the elderly asthmatics. A model of this approach places the patient in the centre of their own care and recognizes the many and divergent management issues that affect the health status and morbidity in older people with asthma.

Specific recommendations for the management of asthma in the elderly

Hence, although highly prevalent, asthma in the elderly can be managed successfully with the help of correct diagnosis, addressing co-morbidities as well as following an individualized and multidisciplinary approach to therapy.

References

2. Drugs Aging 2009; 26 (1):1-22

3. Respir Med 2009; 103:1614-1622

4. Drugs Aging 2005; 22 (12):1029-1059

5. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:690-9

6. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine 2010, 16:55-59

7. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126: 681-7

8. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:702-9

9. NAEPP Working Group Report. Considerations for diagnosing and managing asthma in the elderly (NIH # 96-3662). National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, 1996.

10. Eur Respir Mon 2009; 43:56-76

11. Age and Ageing 2004; 33:185-188