Asthma Exacerbations

Introduction

Last year, 66% of Indians reported asthma exacerbations1

Due to asthma, 78% of Indians missed work or school in previous year1

In the Asia-Pacific region, Indians had the longest average absence from work or school of 16.5 days1

Productivity of Indians decreased by 50% in the previous year due to asthma1

Approximately 15.0 million outpatient visits, 2 million emergency room visits and 5,00,000 hospitalizations occur in the US each year due to acute asthma3

Frequency of high exacerbations are linked with poor quality of life and irreversible decline in lung function1,3,4

Defining the Problem

The Global Initiative for Asthma Management (GINA) guidelines describe asthma exacerbations as follows: “Exacerbations of asthma (asthma attacks or acute asthma) are episodes of progressive increase in shortness of breath, cough, wheezing or chest tightness, or some combination of these symptoms and are characterized by decreases in the expiratory airflow that can be quantified and monitored by measurement of lung function (peak expiratory flow [PEF] or forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1])”.

However, this description lacks a clear definition and several clinical trials have used different definitions of an asthma exacerbation. Hence, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) jointly released a consensus document in 2009 with an aim to standardize the definition of asthma exacerbations as per their severity.

However, these definitions have been developed with respect to clinical trials and may not necessarily be valid in clinical practice. Further information regarding these definitions can be found in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009; 180:59–99 available at http://www.thoracic.org/statements/resources/allergy-asthma/ats-ers-asthma-control-and-exacerbations.pdf

What Exactly Happens in an Asthma Exacerbation?

The hallmark feature of an asthma exacerbation is the surge in the inflammation in the airways. The classical notion is that the cause of the exacerbation is usually attributable to allergens such as dust mites, pollen, etc., leading to predominant eosinophilic inflammation. However, there is data that inflammation in asthma exacerbations is heterogeneous and could involve predominant neutrophils due to viral infections. In fact, viral infection is the most dominant trigger for an asthma exacerbation for both adults and children.

Evolution of an Exacerbation in the Airways

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease with variable episodic attacks. Chronic inflammation in

asthma is associated with sub-epithelial fibrosis, smooth muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy, mucous gland hyperplasia

and neo-vascularization. On the entry of an allergen or some other trigger, there is a substantial increase in this

chronic inflammation (Figure 1). This acute inflammation in asthma is associated with bronchoconstriction, plasma

exudation/oedema, vasodilatation and mucous hypersecretion, all of which are the pathophysiological features of an

asthma exacerbation. The clinical result of these events is that the patient experiences increased breathlessness,

coughing, wheezing and chest tightness. The severity of the exacerbation is dependent on the extent of this acute

inflammation and, hence, it is essential to treat this acute inflammation.

Exacerbations therefore,

are a consequence of acute-on-chronic inflammation induced by the triggers, viral infections, dust, pollen, etc.

Clinical Evolution of an Exacerbation (Figure 2)

The analysis of the 425 exacerbations in the FACET* trial revealed the following:

- The exacerbations were characterized by a gradual decline in the PEF over 5–7 days, followed by a more rapid fall over 2–3 days.

- The increase in symptoms and the use of a rescue beta2-agonist were similar in pattern to the fall in the PEF.

Knowing the rate of change in the PEF and the symptoms as an exacerbation develops might help to

determine whether the exacerbations can be identified at an early stage. This would enable treatment to be started

earlier — thereby reducing the severity of the exacerbation, and this is the idea behind the SMART regimen

(Figure 2).

{*FACET: The Formoterol and Corticosteroids Establishing Therapy trial was a

double-blind, randomized, parallel-group trial with 852 patients, who had been on inhaled corticosteroids [ICS]

before the start of the study, receiving either low-dose budesonide (100 mcg), low-dose budesonide plus

formoterol (12 mcg), high-dose budesonide (400 mcg), or high-dose budesonide plus formoterol (12 mcg) twice

daily along with a short-acting beta2-agonist (SABA) as rescue medication. The primary endpoint was the

incidence and the rate of severe and mild exacerbations. The study concluded that in patients who have

persistent symptoms of asthma despite treatment with ICS, the addition of formoterol to budesonide may be

beneficial in improving asthma control.}

Impact of Exacerbations

Exacerbations not only impact the quality of life in patients but are also detrimental to the lung

function over the long term. There have been reports of accelerated loss in lung function to the extent of 30.2 ml

per year-decline in the FEV1 after one severe exacerbation annually (a follow-up of 11 years).

Exacerbations

activate pathways of inflammation and remodelling, resulting in deterioration of lung function. Accelerated loss of

lung function, in turn, puts patients at increased risk of recurrent exacerbations, resulting in a vicious cycle

that may promote the exacerbation-prone phenotype (Figure 3).

At Risk for Exacerbation: The Likely Candidates

Patients who are at risk for exacerbations include the following:

- History of near-fatal asthma requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation

- Hospitalization or emergency room visit for asthma in the past year

- Currently using or recently stopped using oral corticosteroids

- Currently not using ICS

- Over-dependent on reliever medication, especially those using more than one canister of salbutamol (or equivalent) per month

- History of psychiatric disease or psychosocial disease, including the use of sedatives

- History of poor adherence to asthma medication and/or written asthma action plan

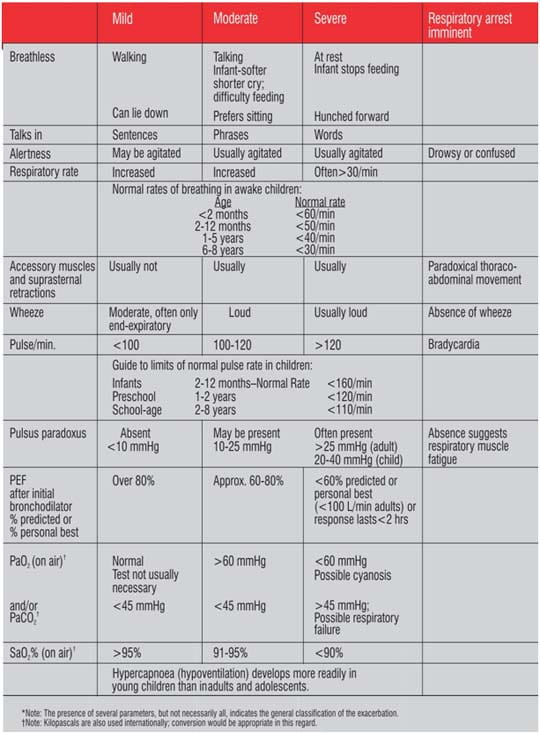

Classifying the Severity of an Exaberation

Classifying the severity of asthma exacerbations is important as it also helps identify the correct

treatment approach. The following approach (Table 1) has been proposed by the GINA guidelines.

In addition to

the GINA guidelines, a more concise approach has been proposed by the National Asthma Education and Prevention

Program (NAEPP): Expert Panel Report 3, the asthma management guidelines for the United States of America

(USA).

This can be accessed at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/11_sec5_exacerb.pdf

Treatment and Management

Treating an asthma exacerbation early is the most effective management strategy and, for this, it is essential that patients learn to understand the signs and symptoms for taking appropriate action. A mild exacerbation, although considered just outside the normal variation of day-to-day symptoms, can be easily treated at home (Figure 4):

Figure 4: Home treatment of a mild asthma exacerbation

A moderate exacerbation

requires an emergency room visit, while a severe exacerbation may result in hospitalization. A life-threatening

exacerbation where respiratory failure is imminent could possible require an admission into the intensive care

unit.

Figure 5 describes the approach that the GINA guideline recommends for managing asthma

exacerbations in acute-care settings such as the emergency room or hospital or intensive care unit.

Figure 5: Management of asthma exacerbations in acute-care settings

Oral corticosteroids are usually as effective as those

administered intravenously and are preferred because this route of delivery is less invasive and less

expensive.

If vomiting has occurred shortly after administration of oral corticosteroids, then an equivalent

dose should be re-administered intravenously. In patients discharged from the emergency department, intramuscular

administration may be helpful, especially if there are concerns about compliance with oral therapy. Oral

corticosteroids require at least 4 hours to produce clinical improvement.

Daily doses of systemic

corticosteroids equivalent to 60–80 mg methylprednisolone as a single dose, or 300–400 mg hydrocortisone

in divided doses, are adequate for hospitalized patients, and 40 mg methylprednisolone or 200 mg hydrocortisone is

probably adequate in most patients.

Preventing Asthma Exacerbation

The age old wisdom of “Prevention is better than Cure” holds true even in the case of

asthma exacerbations. Indeed, preventing asthma exacerbation is an important component of establishing asthma

control and is one of the key recommendations of the various asthma guidelines.

The most effective and

proven strategy to reduce the risk of asthma exacerbations is the regular use of ICS. The regular use of combination

of ICS and long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs) also confers additional benefit in terms of reducing the risk of

asthma exacerbations.

One of the strategies to reduce the risk of asthma exacerbations, which has

emerged in the recent years, is using a budesonide/formoterol combination as the single maintenance and reliever

therapy (SMART). The basic principle behind SMART is the pharmacological properties of formoterol such as fast onset

of action and dose–response effect, which enables the budesonide/formoterol combination to be used as

maintenance as well as reliever.

Large-scale, randomized, blind clinical studies in patients with

asthma, aged 12 years or older, have highlighted the benefits of the budesonide/formoterol maintenance and reliever

therapy, which has shown a consistent decrease in the rate of asthma exacerbations (Figure 6).

Additionally, the other

therapeutic options to reduce the risk of asthma exacerbations, which are currently being studied, are monoclonal

antibodies such as omalizumab (directed against immunoglobulin E), mepolizumab (directed against interleukin-5) and

bronchial thermoplasty. Though the initial clinical studies have shown some positive results, it could be some time

before these treatments become easily available for the reduction of asthma exacerbations.

Summary

- Exacerbations are the unpredictable aspect of asthma, which can be prevented.

- Despite the wide availability of asthma treatments, the prevalence of asthma exacerbations is high.

- Although asthma exacerbations have been precisely defined for the purpose of clinical research, there is still no clarity on their definition in clinical practice.

- Asthma exacerbations seem to be more common in boys than in girls before puberty.

- However, in adulthood, it is the women who seem to have exacerbations more frequently than men.

- The dominant trigger for exacerbations in both children and adults is viral infection.

- Asthma exacerbations can be managed at home or in a hospital, depending on their severity.

- The first-line treatment for asthma exacerbations, irrespective of the severity, is SABAs.

- The exacerbations also require treatment with oral or systemic steroids.

- The combination of ICS and LABA is effective in reducing exacerbations.

- Use of a LABA without ICS is inappropriate in asthma and may increase exacerbations.

References

- Respirology. 2013; 18(6):957–967

- Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010; 120 (12):511–517

- Clin Exp Allergy. 2009; 39(2):193–202

- Prim Care Respir J. 2007; 16(1):22–27

- Global Initiative for Asthma Management (GINA) Guidelines–Update 2012

- J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008; 122:662–668

- Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009; 180:59–99

- Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 11:181–186

- J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 128:1165–1174

- Pharmacol Ther. 2011; 131(1):114–129

- Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999; 160(2):594–599

- Am Fam Physician. 2011; 84(1):40–47

- J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011; 128:257–63

- Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2010; 23(2):88–96