Asthma and Sports

Exercise-induced asthma (EIA) and exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB) are the terms that are usually used to describe the transient narrowing of the airways that follows vigorous exercise. However, there are some minor yet important differences in these two conditions.

The term, EIA, is used to describe symptoms and signs of asthma provoked by exercisewhile EIB describes a reduction in lung function after an exercise test or a natural exercise and is usually seen in elite athletes who do not generally have asthma. EIB occurs in approximately 10% of individuals who are not known to have asthma. These patients who have EIB but not asthma do not exhibit the typical features of chronic asthma (i.e., frequent daytime symptoms, nocturnal symptoms, impaired lung function). Exercise can be the only stimulus that triggers respiratory symptoms in these patients.

Most individuals who experience EIB will have normal baseline lung function, and spirometry alone is not adequate to diagnose EIB. In patients evaluated for EIB who have a normal physical examination and normal spirometry, bronchoprovocation testing is recommended.

The airway inflammation pattern is also different in these two conditions; inflammation in asthma is usually associated with eosinophilia whereas isolated EIB in elite athletes seems to be more associated with neutrophilic or mixed-type airway inflammation and, hence, the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids in this cohort is very unclear. Hence, the first-line treatment to minimize or prevent symptoms of EIB is the prophylactic use of short-acting bronchodilators shortly before exercise. Inhaled corticosteroids are a first-line therapy in terms of controller medications for athletes who have asthma and experience EIB.

Because of such close similarities between these terms, both are used interchangeably in much of the literature published across the world. Hence, it must be borne in mind that either term signifies the transient narrowing of the airways following exercise and that atopy causing chronic asthma and bronchial hyper-responsiveness to thermal, mechanical or osmotic stimuli (seen more commonly in elite athletes) are not mutually exclusive.

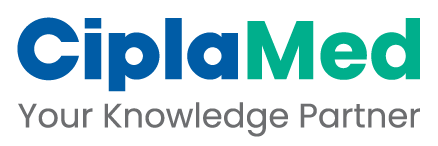

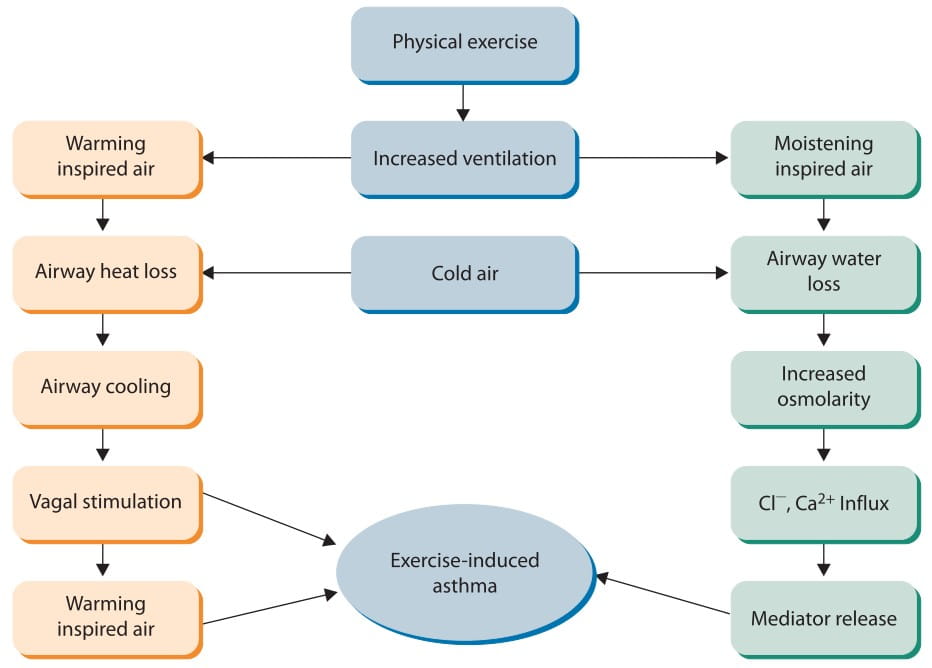

The exact mechanism of exercise-induced asthma is not fully understood. However, currently, there are two main accepted hypotheses to explain the relationship between physical activity and exercise-induced asthma (Figure 1).

In one of the hypotheses, it has been suggested that airway cooling due to respiratory heat loss followed by hyperaemia and pulmonary vasodilatation could be the reason for asthma symptoms after exercising. Airway cooling may stimulate receptors in the airways, causing bronchoconstriction through vagal stimulation. Furthermore, inhalation of cold air can induce vasoconstriction of the bronchial circulation, resulting in secondary reactive hyeraemia, further leading to oedema and airway narrowing. There is also considerable evidence to indicate that EIA is effected through the release of mediators from mast cells and other inflammatory cells of the airways.

The other hypothesis suggests that water loss from the airways may be the reason for EIA. The reason for this water loss is the increasing ventilator rate, especially during inhalation of cold air. This respiratory water loss increases the periciliary fluid lining the surface of respiratory mucosal membranes, leading to the influx of chloride and calcium ions into the bronchial epithelium, which further results in mediator release and, consequently, the pathophysiology of exercise-induced asthma.

Because inflammation has been understood as the pathophysiologic basis for chronic asthma, evidence for inflammation has been studied in EIA and similar mediators have been found. Some studies have shown that exhaled nitric oxide (NO) changes after exercise in patients with EIA, and that this change is directly correlated with the drop in the forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) after exercise. Studies have shown other inflammatory markers to be present in patients with EIA at rest and also after exercise. There are also studies showing a 50% incidence of a late asthmatic response in exercise-induced asthma, supporting the evidence for inflammation in EIA.

This suggests that EIA is more than just a set of independent events after exercise; rather, frequent exercise may lead to chronic inflammatory changes in the airways. This is an important concept when treatment is considered; daily anti-inflammatory controller medications for the inflammation may be required in addition to pre-exercise medications.

The usual presenting symptoms of EIA include cough, wheezing, shortness of breath or chest tightness during or after usually 6-8 minutes of strenuous exercise. The other symptoms that may occur in some patients because of EIA and should be considered during diagnosis are the subtle symptoms of 'feeling out of shape', headaches, abdominal pains, muscle cramps, fatigue or dizziness (Table 1).

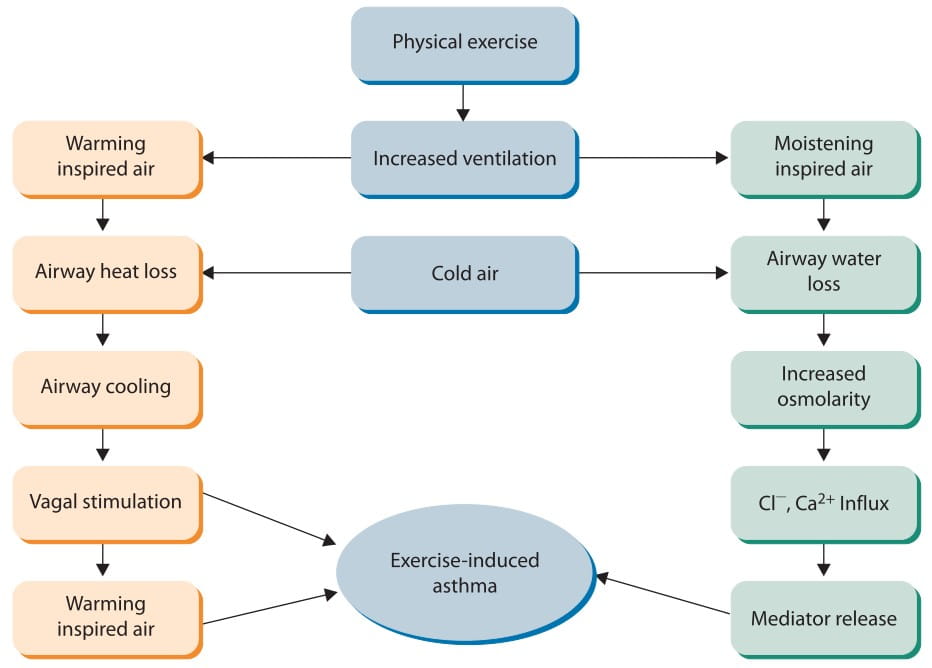

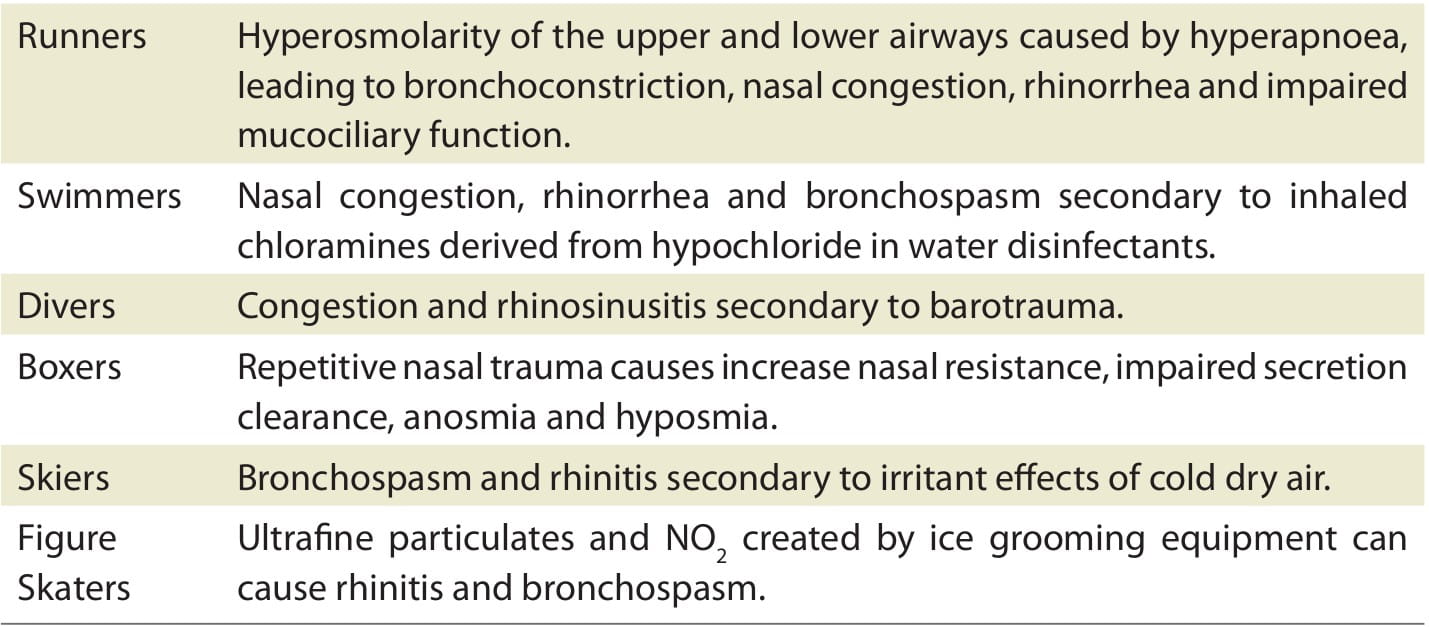

Different types of sports may result in different clinical presentations (Table 2).

- It is important that all persons dealing with an athlete be aware of any respiratory symptoms and brings them to the attention of the athlete so that he/she seeks proper medical attention.

- Sometimes athletes are poor perceivers of their symptoms and may assume that the reason for symptoms is 'feeling out of shape'.

- Factors such as peer pressure, embarrassment, fear of losing position on the team and misinterpretation of symptoms as post-exercise fatigue may cause patients to deny symptoms.

- Cough could be a more frequent symptom compared to wheeze and excess mucus.

- Chest pain may manifest as a symptom of EIA in healthy children and adolescents.

- Other more subtle symptoms include prolonged difficulty in eliminating upper respiratory illness, -locker room cough', difficulty in sleeping due to nocturnal symptoms, the feeling of having heavy legs, and avoidance of activity.

- Seasonal change in fitness, sore throat in young children, and worsening problems with exposure to certain triggers like house dust mites, moulds, etc., may all be presenting symptoms of EIA.

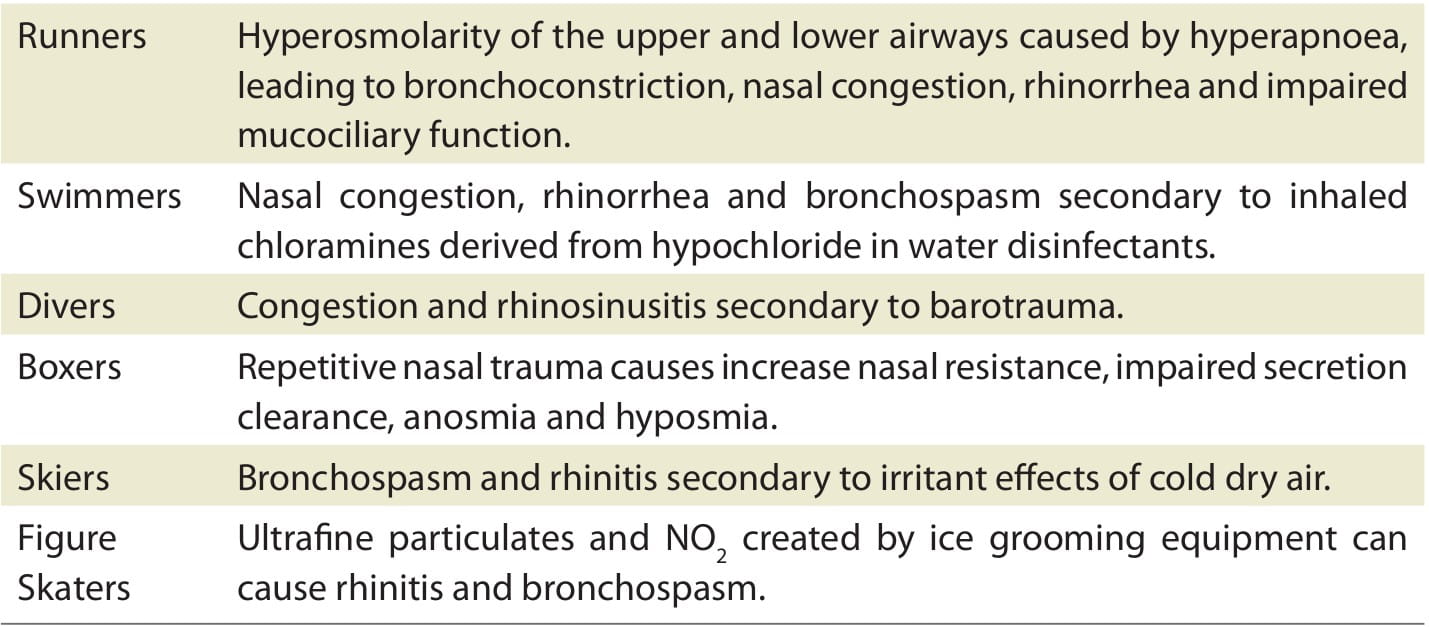

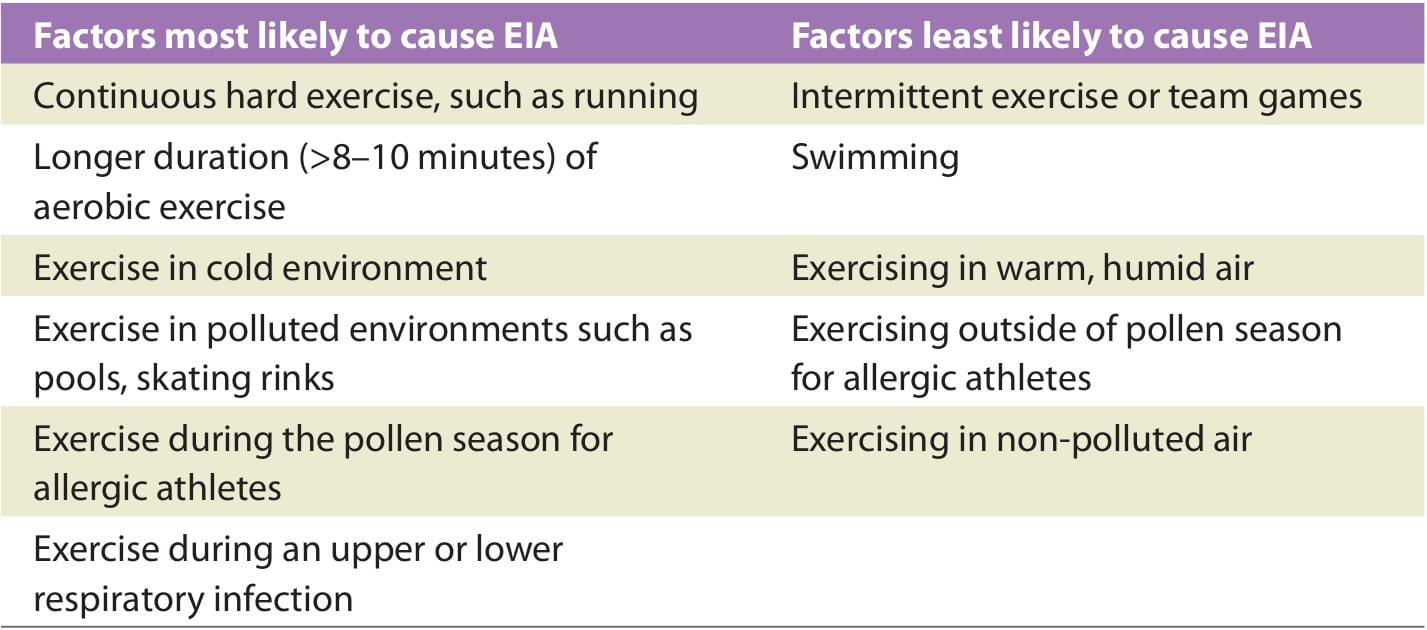

Although symptoms are usually what triggers the athlete to seek medical attention, it has been shown that self-reported symptoms do not necessarily correlate well with the presence of EIA and can give both false-positive and false-negative results. However, to solve this dilemma, a good patient history, including family history of asthma or a personal history of recurrent allergic rhinitis or sinusitis, which increase the likelihood of EIA, should be taken into account. The following are the factors that should also be considered during the diagnosis of EIA (Table 3):

After a thorough history is taken, a physical exam should be performed, including ear, nose and throat examination for signs of nasal allergies, sinusitis or otitis; a cardiac exam to look for murmurs or arrhythmias; and a chest exam to evaluate for wheezing, rales or rhonchi. All this is to rule out the alternate diagnosis and confirm the presence of EIA.

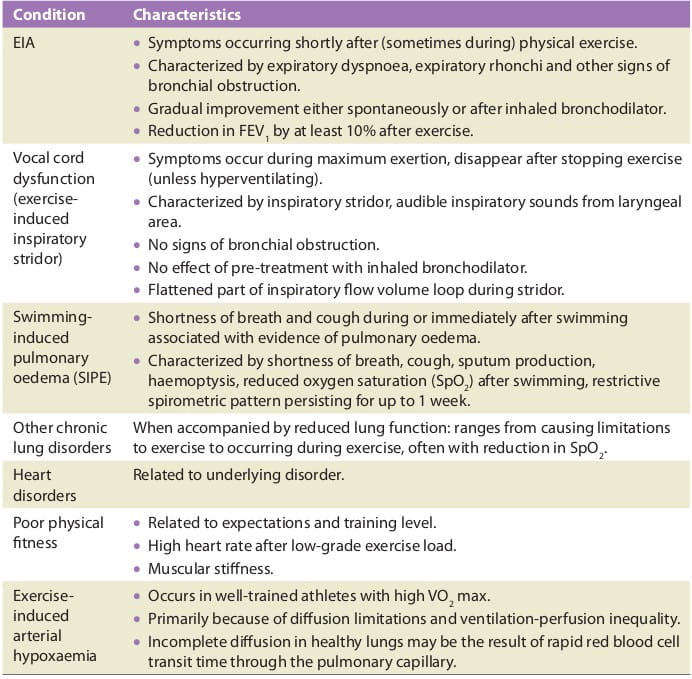

There are several important differential diagnoses to EIA and EIB in an athlete, such as laryngeal inspiratory stridor (also known as exercise-induced vocal cord dysfunction) and hyperventilation during exercise. These conditions should be borne in mind, as many such patients have been given unnecessary drugs for the treatment of asthma, including both inhaled steroids and beta2-agonists, which will have no effect upon the exercise-induced laryngeal stridor (most often occurs in young well-trained athletic girls from approximately 15 years of age).

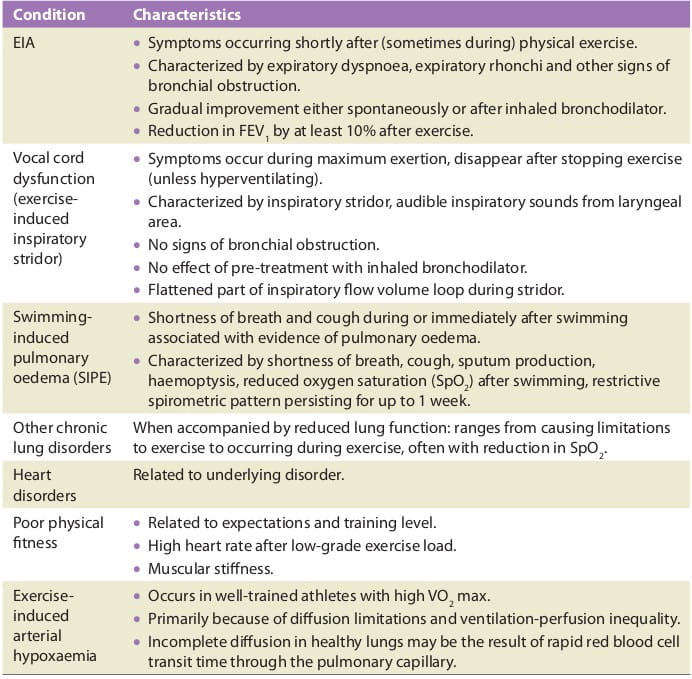

Table 4 gives a brief account of the alternate diagnosis of exercise-induced asthma in sports.

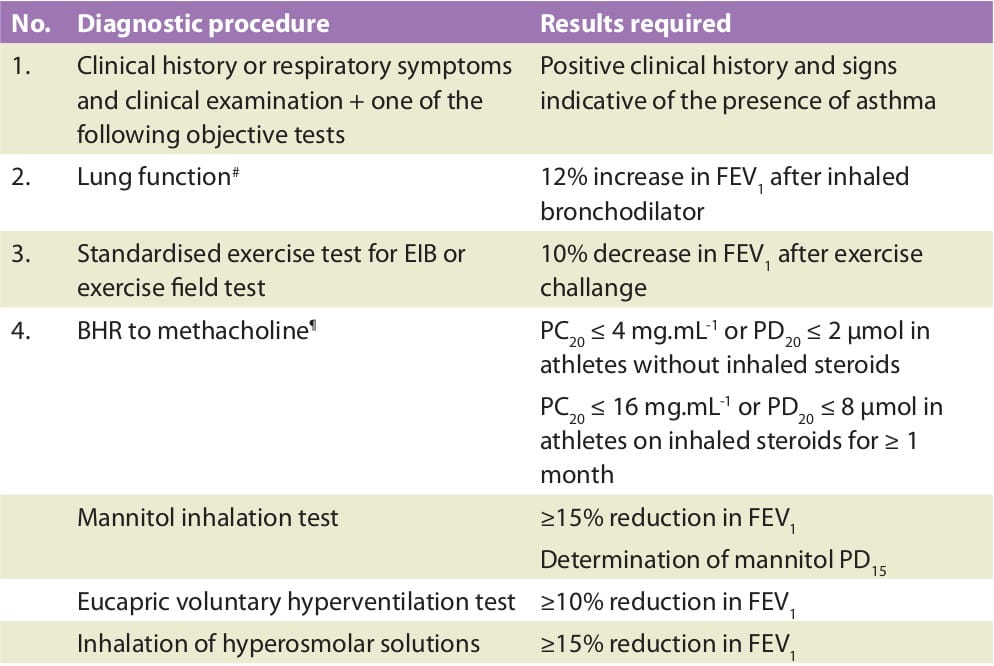

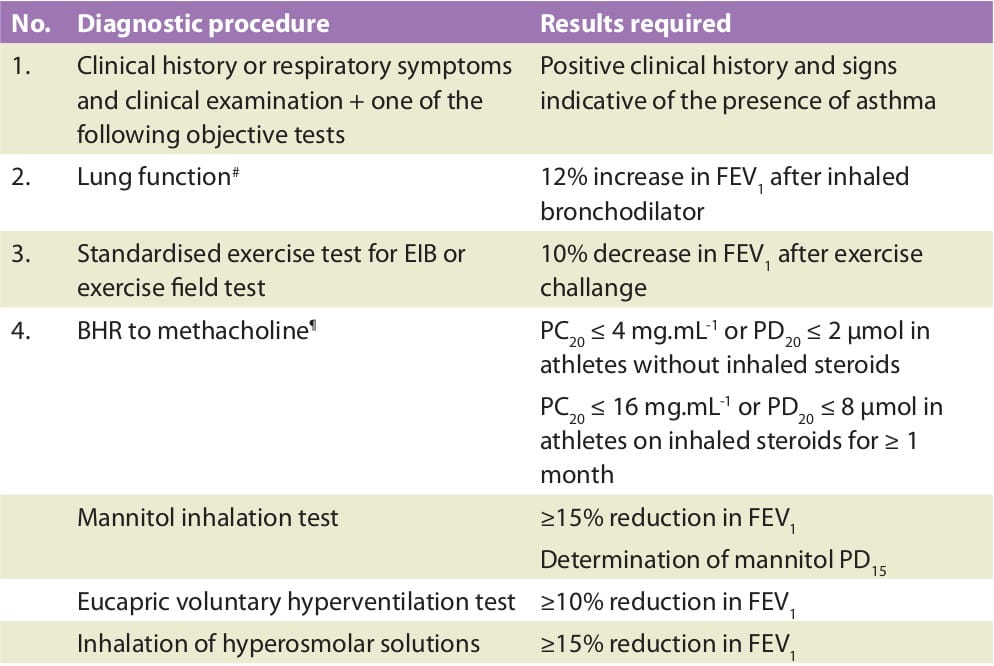

When an athlete participates in international sports, a combination of the medical history and laboratory tests should be documented as a basis for the diagnosis of asthma and the possibility of using asthma medication. The laboratory tests may either be the demonstration of EIB, reversibility to inhaled beta2-agonists or the demonstration of bronchial hyperresponsiveness to direct or indirect stimuli.

- EIB: A standardized exercise test at a high enough and standardized exercise load, breathing air of stable temperature and humidity (20-25°C and 40-50% relative humidity) should be employed, either in a laboratory or as a field test, demonstrating at least 10% reduction in FEV1 from baseline after exercise. The type of exercise may be varied in accordance with the type of sport practiced, although running or cycling for 8 minutes such that it allows the patient to achieve >90% of peak heart rate by 2 minutes into the challenge and maintaining it for 6 minutes of the challenge is most often the best suited for provoking EIB.

- Responsiveness to inhaled bronchodilators: An increase in the FEV1 of 12% (in percent of baseline or of predicted value) before and after inhalation of a bronchodilator, preferably an inhaled beta2-agonist, administered by a pressurized metered dose inhaler, dry powder inhaler or a nebulizer.

- Direct bronchial responsiveness: In athletes who have received inhaled corticosteroids for a period of 3 months or longer, a PC20* to either histamine or methacholine less than 16 mg/ml or a PD20+ less than 3.2 mg (16 ?mol) should be documented. In athletes who have not received such medication, the levels should be PC20 ≤4 mg/ml or PD20 ≤0.8 mg (4 ?mol). In laboratories with their own developed reference values for bronchial responsiveness, these could be employed after the references levels of the laboratory have been scientifically documented.

- Other measures of indirect bronchial responsiveness: A reduction in FEV1 of 10% before and after the provocative agent is considered adequate and comparable with the stimulus of the standardized exercise test. The test can be inhalation of cold, dry air, or dry air as in the eucapnic hyperventilation test. Other test agents such as inhalation of hyperosmolar aerosols as hypertonic saline or mannitol may also be used. For mannitol, the dose inhaled to cause a decrease in the FEV1 of 15% is determined (PD15).

*PC20: The provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in the FEV1

*PD20: The provocative dose causing a 20% fall in the FEV1

Table 5 describes the procedure for the diagnosis and the application to obtain approval for using inhaled steroids and/or inhaled beta2-agonists in sports. As a change of existing rules may be issued, the responsible physician should keep informed through the websites of WADA and IOC (international Olympic Committee) for the Olympic Games. As medical regulations for the assessment of bronchial hyperresponsiveness through pharmacological provocation may vary somewhat between different countries and country-specific regulations should be observed (such as regulations established by the National Anti- Doping Agency for India), a combination of positive responses to step 1 and either steps 2, 3 or 4 is required.

- Obtain a history of the respiratory symptoms and perform a clinical examination with focus on the signs of bronchial obstruction. Diagnosis should be confirmed through a confirmatory objective test such as an exercise challenge.

- In elite athletes, usually, cough is the most frequent symptom and develops significantly more frequently than wheeze or excess mucus.

- Healthy children and adolescents may present with chest pain as a manifestation of EIA.

- Seasonal change in fitness, sore throat in young children, and worsening problems with exposure to certain triggers during exercise may all be presenting symptoms of EIA.

- Exercise-induced laryngeal stridor is more common among highly trained female athletes during adolescence.

- For exercise challenge tests, running provokes EIB in children more easily than cycling.

- Running for 6-8 minutes provokes a greater decrease in post-exercise FEV1 than running for shorter or longer time periods.

- One useful way to standardize the diagnosis of EIA in athletes is to employ a motor-driven treadmill with an inclination of 5.5%.

- Once on the treadmill, the speed is rapidly increased until a steady heart rate of ∼95% of the calculated maximum is reached, and this should be maintained for 4-6 minutes.

- Running is performed at a room temperature of ∼20° C and a relative humidity of ∼40%.

- Lung function is measured before running, immediately after cessation of running, and 3, 6, 10, 15 and 20 minutes after running.

- When adding an extra stimulus to the exercise test by combining running on treadmill with inhalation of dry cold air of -20°C, the sensitivity of the test is markedly increased while simultaneously maintaining a high degree of specificity.

Management of asthma in athletes is similar to management in non-athletes, with attention to patient education, reduction of relevant environmental exposures, treatment of associated comorbid conditions, individualized pharmacotherapy, prevention of exacerbations and regular follow-up. The management of the athlete with asthma should follow current national or international guidelines (like Global Initiative for Asthma [GINA]). The following is a management flow chart recommended by the IOC.

The prevention and management of EIB is a key issue in athletes. The following are the steps recommended by the Australian Association for Exercise and Sports Science:

- Obtain good control of asthma with inhaled corticosteroids.

- Add long-acting beta-agonists (LABAs) and, when necessary, LTRA, chromones, anticholinergics (rarely).

- Ensure appropriate care of metered dose inhalers and spacers.

- Pre-exercise warm-up.

- Pre-exercise medication.

- Short-acting beta-agonists (SABAs)

- LTRAs and/or chromones (uncommonly)

- Avoid unfavourable environmental conditions when possible.

- Reduce the effects of cold air with masks during training.

The non-pharmacological management of asthma in athletes is important. This includes identifying and reducing exposure to asthma triggers whenever possible and especially during training. Prophylaxis of EIA includes premedication and warm-up. A beta-agonist should be used if asthma symptoms develop and exercise should be restarted. Traditionally premedication with inhaled beta-agonists 15 minutes before exercise improves EIA symptoms and exerts a protective effect.

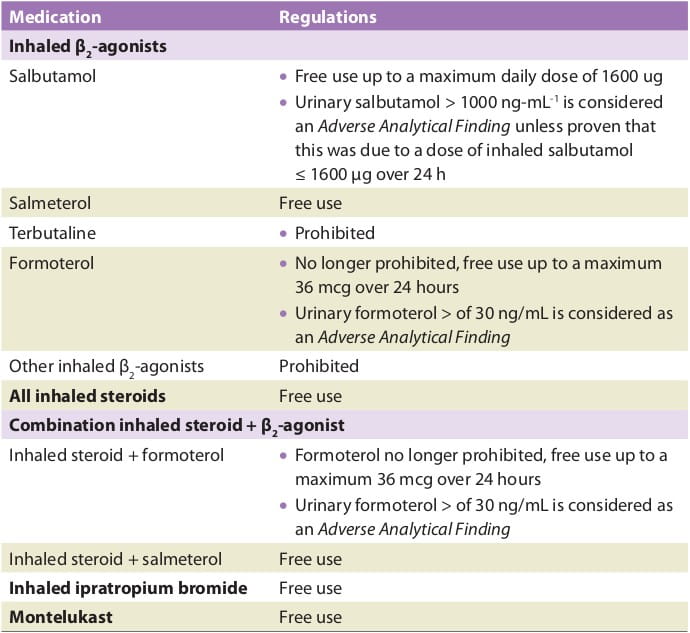

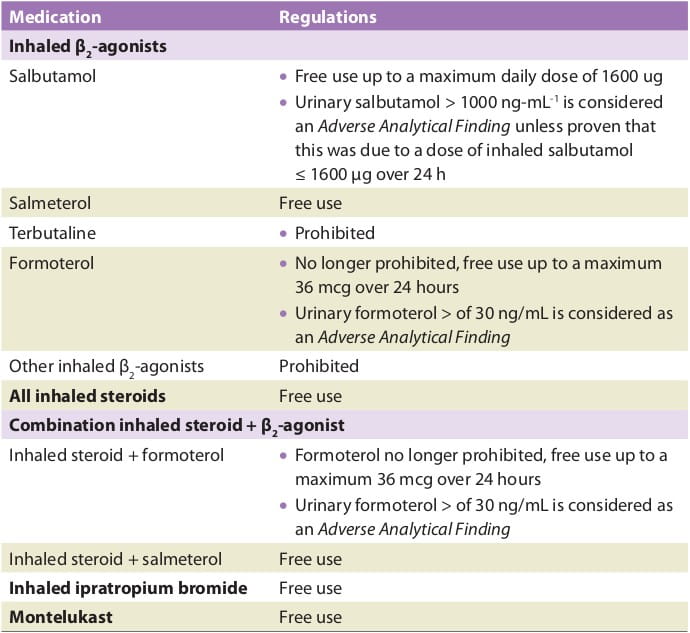

Drug treatment of asthma in elite athletes should follow standard guidelines, with treatment individualized to achieve asthma control and the effects of the treatment monitored. Any medications prescribed must comply with the WADA regulations. All beta2- adrenoceptor agonists (beta2-agonists) and, in particular, oral preparations are prohibited. Inhaled corticosteroids and some inhaled beta2-agonists can be used in accordance with the relevant section of the International Standard for TUE. Systemic corticosteroids are prohibited and require a standard TUE.

Table 6 gives an overview of the asthma drugs for which the athlete must apply for use through a TUE from January 1, 2012, according to the WADA regulations.

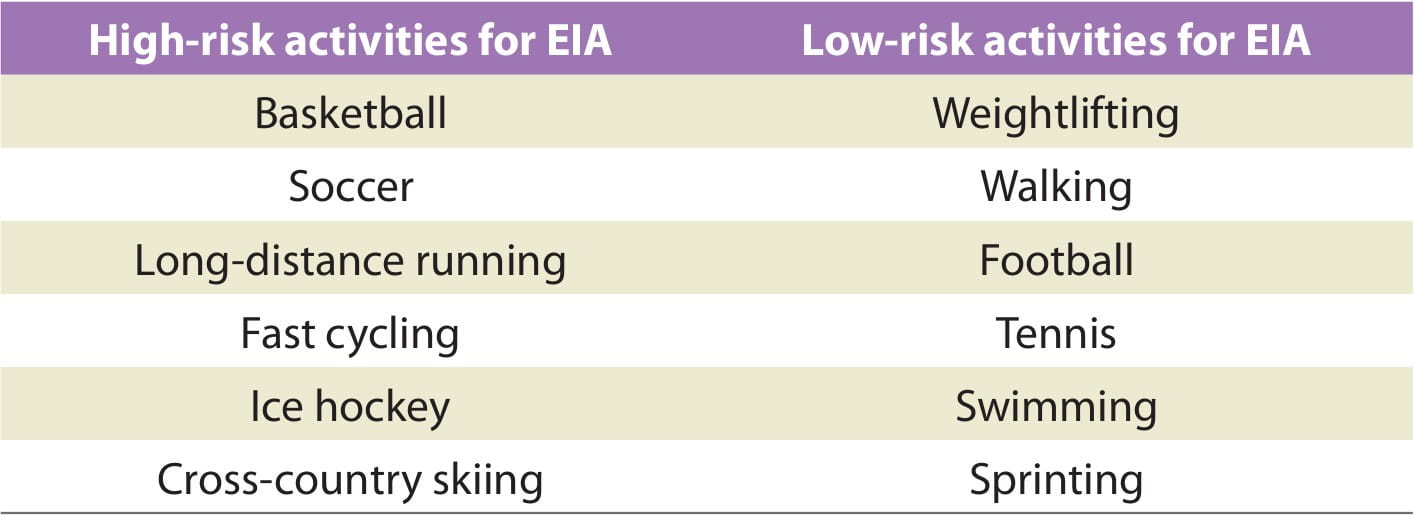

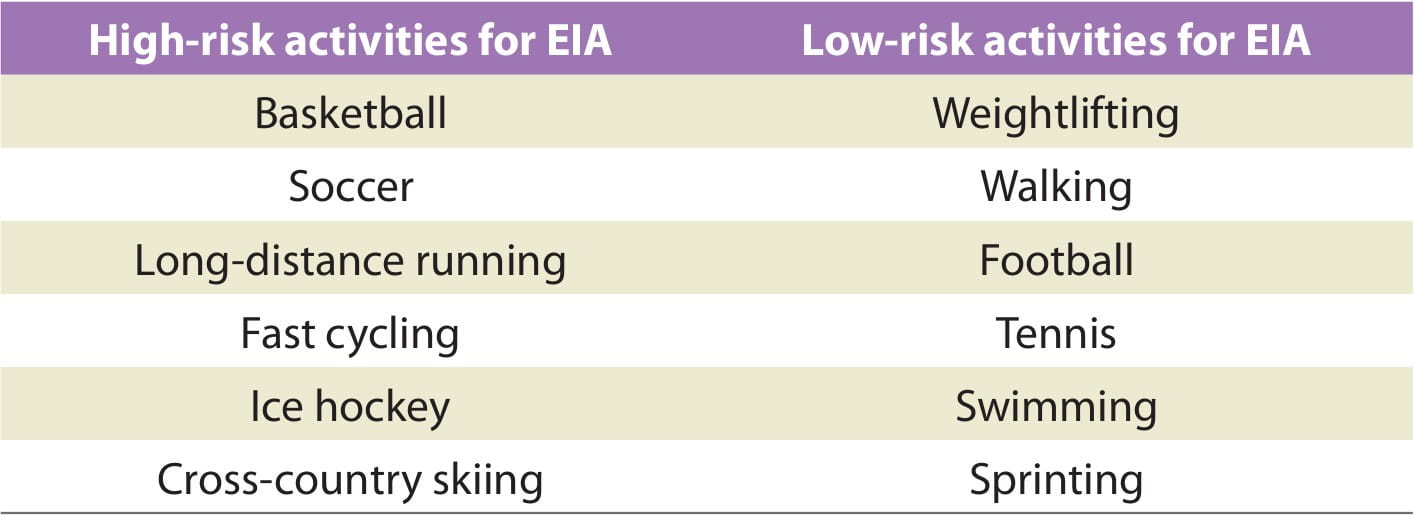

- Long-distance or cross-country running are particularly strong triggers because they are undertaken outside in cold air with short breaks.

- Team sports such as football or hockey are less likely to cause asthma symptoms as they are played in brief bursts with short breaks in between.

- Swimming is an excellent form of exercise for people with asthma. The warm humid air in the swimming pool is less likely to trigger symptoms of asthma. However, swimming in cold water or heavily chlorinated pools may trigger asthma.

- Yoga is a good type of exercise for people with asthma as it relaxes the body and may help with breathing.

People with asthma may need to take special care when doing adventure sports. Some of them are mentioned below:

- Scuba diving: In recent years, medical opinion has recognized that people with controlled asthma symptoms can take part in scuba diving. However, asthmatics may have greater problems when scuba diving because of the triggers to which they are exposed while diving (such as cold air, exercise, stress, emotion). Regulations on scuba diving by people with asthma vary between countries. For example, in Australia, it is necessary for all intending scuba divers to pass a diving medical examination performed by a diving medical doctor before being certified as fit to scuba dive, and, recently, some persons with mild-to-moderate, well-controlled asthma have been permitted to dive. In India, there are no such caveats for scuba diving. However, in the UK, the British Sub-Aqua Club, a national governing body for this sport, suggests that those with mild, controlled asthma may dive given the following:

- They do not have asthma that is triggered by cold, exercise, stress or emotion.

- Their asthma is well-controlled.

- They have not needed to use a reliever medication or had any asthma symptoms in the previous 48 hours.

- Their peak flow must be within 10% of their best value for at least 48 hours before diving.

- Mountaineering: The mountain environment contains several triggers for people with asthma (cold, dry air and exercise). If asthmatics are physically fit with well-controlled asthma and are prepared adequately for their trip, then they should not be restricted in their activity.

- Skiing: Skiing involves many of the same asthma triggers as mountaineering. Cross- country skiing is thought to be a stronger trigger for asthma than downhill skiing or mountaineering. People with well-controlled asthma should be able to ski safely.

- Parachute jumping: As a general rule, asthmatics can parachute jump or skydive if their asthma is completely controlled, and cold air and exercise do not trigger their asthma.

The following table compiles a list of high-risk and low-risk activities for asthmatics with exercise as a trigger.

- A warm-up of 10-15 minutes should include calisthenics along with stretching exercises, with an objective of reaching 50-60% of the maximum heart rate.

- Breathing through the nose may allow cool, dry air to be humidified and warmed.

- A warm-down of 10-15 minutes post-exercise may avoid the rapid re-warming that may cause any airway obstruction to occur.

EIA is a condition that may be found in athletes at any level, from recreational to elite athletes. However, if properly treated, most individuals can exercise to their fullest capacity and potentially reach elite athlete status. The diagnosis may be very obvious, but some subjects may present with unusual symptoms. It is important for the physician, certified athletic trainer and coach to be aware of the possible symptoms that may suggest this condition. It is also important to offer the correct treatment for the asthmatic athlete in accordance with his/her disease severity and the rules of the sport. The aim is to help athletes with asthma fulfil their potential in physical activity and sports in spite of their illness.

- World Anti-Doping Agency: www.wada-ama.org

- International Olympic Committee: www.olympic.org/

- Indian Olympic Committee: www.olympic.ind.in/

- National Anti-Doping Agency: http://www.nada.nic.in/

- Sports Authority of India: http://www.sportsauthorityofindia.nic.in

- British Sub-Aqua Club: www.bsac.com

- British Mountaineering Council: www.thebmc.co.uk

- UK Sport: www.uksport.gov.uk

- European Lung Foundation: http://www.european-lung-foundation.org

- www.asthma.org.uk

1. Breathe 2005; 2:163-168

2. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 21(2):88-92

3. Allergy 2008; 63:387-403

4. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35(9):1464-1470

5. Allergy 2008: 63:953-961

6. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119:1349-58

7. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1938228-clinical (as accessed on 26.3.12)

8. http://www.worldallergy.org/professional/allergic_diseases_center/asthma_and_sports/ (as accessed on 9.2.12)

9. Eur Respir J 2011; 38:713-720.

10. J Sci Med Sport 2011; 14:312-316

11. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122:254-60

12. Factfile: Exercise and asthma. Last updated July 2009; www.asthma.org.uk (as accessed on 04.04.2012)

13. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2011; 14:312-316

14. American College of Sports Medicine-s Certified News 2003; 13 (3):1-4

15. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008; 122:238-46.