COPD Management Beyond the Lungs

Co-Morbid with Osteoporosis

When it comes to managing a COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) patient, the focus is directed primarily towards the lung function; but, it is an established fact that there is more to the disease than just airflow obstruction, with COPD often being associated with a wide variety of systemic effects. In fact, it has been reported that 84% of COPD patients have one or more co-morbidities. These co-morbidities, therefore, call for an integrated approach towards COPD management.

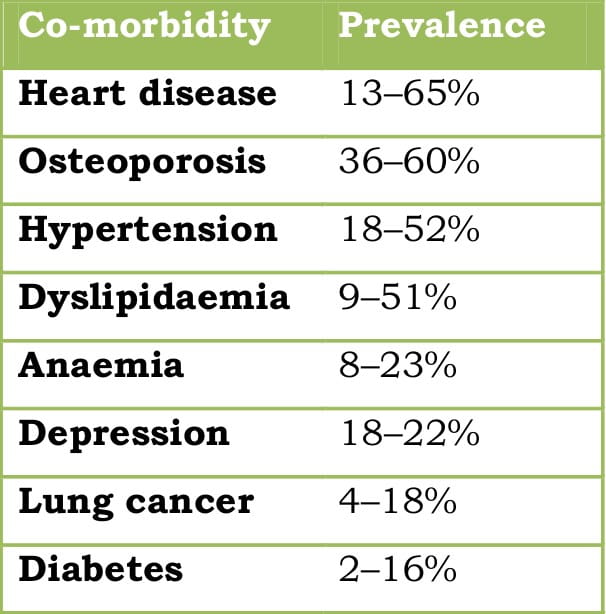

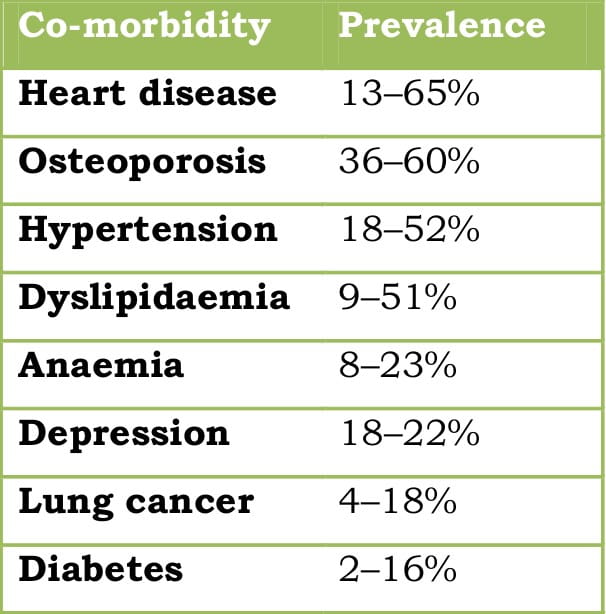

Some of the common co-morbidities are tabulated below.

Table 1: Commonly seen co-morbidities in COPD

”Osteoporosis is a frequently encountered co-morbidity in COPD and is increasingly being appreciated as a crucial therapeutic target.”

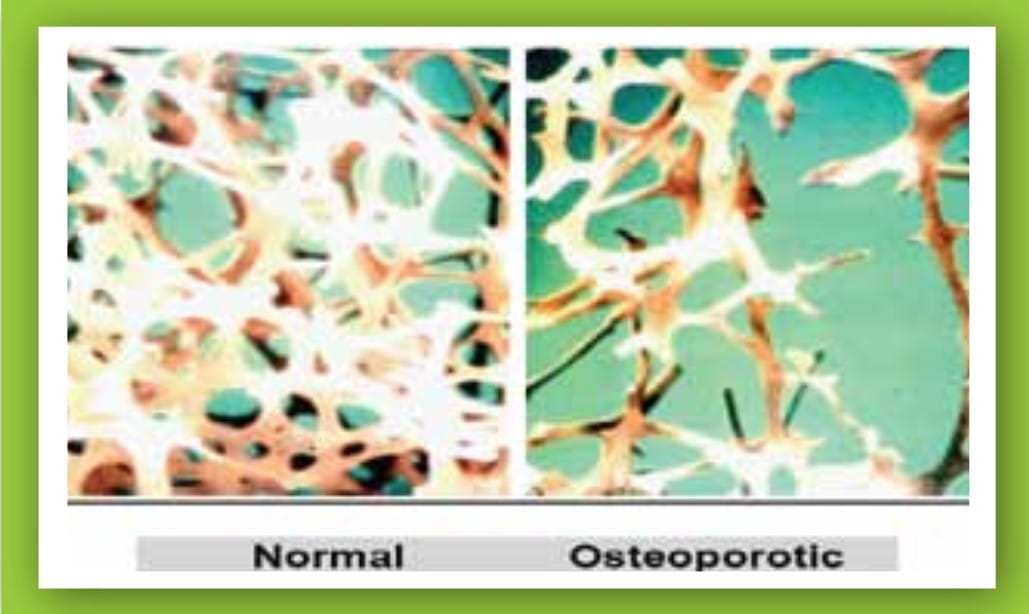

The presence of airflow obstruction is linked with an increased risk of osteoporosis, compared with normal lung function. It is speculated that the prevalence of osteoporosis in COPD is 2- to 5-fold higher, compared to age-matched subjects without airflow obstruction. It has been reported that 35-72% of patients with COPD are osteopenic, whereas the incidence of osteoporosis ranges from 36% to 60%. It appears that osteoporosis is seen with an increased prevalence in patients with more severe disease; nevertheless, severe bone thinning may also occur in patients with less severe airways obstruction. In a recent study carried out in 37 Indian patients with severe-to-very severe COPD, 73% were found to have either osteopenia or osteoporosis.

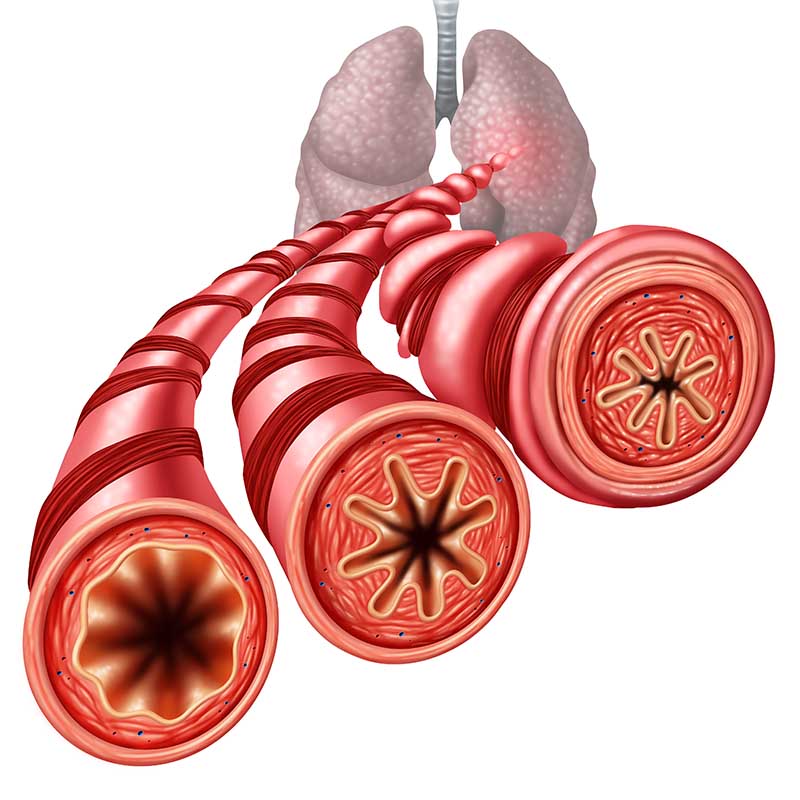

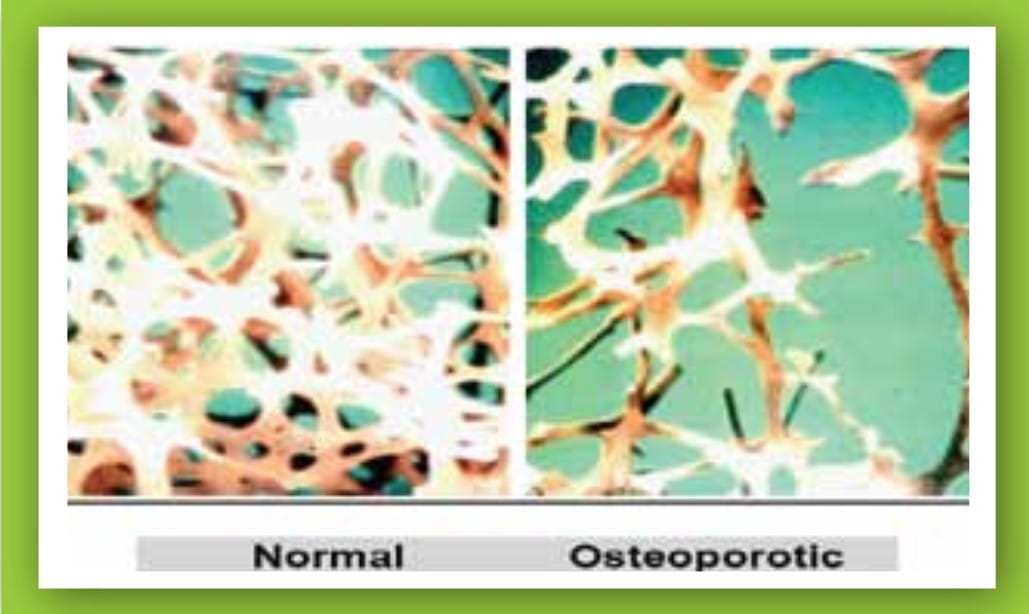

Figure 1: Micrographs of the normal and osteoporotic bone

COPD has been reported as an independent predictor of reduction in bone mineral density (BMD) and the risk of vertebral fracture. The fracture risk has been found to correlate with the disease severity.

In mild COPD, vertebral deformity has been reported in around 12% of cases and more COPD patients than healthy people have at least one severe vertebral fracture (odds ratio [OR] = 3.75). Another study reported at least one vertebral fracture in about 40% of COPD patients, with a strong association between disease severity and fractures, particularly in men.

Talking about women, the average number of vertebral deformities has been reported to increase almost 2-fold in severe COPD, compared to moderate COPD.

Another prospective study sought to examine the patterns of co-morbidities in newly diagnosed COPD patients and it was seen that COPD patients have a greater risk of osteoporosis and fractures (relative risk [RR] = 3.1 and 1.6, respectively) within the first year of diagnosis as evaluated against subjects without COPD.

The findings of the large Danish register study (data of >1, 25,000 cases of fracture) reveal that the use of corticosteroids in COPD is coupled with an increased risk for hip and vertebral fracture (RR = 1.63 and 1.23), but not for forearm fractures. Another large register-based study observed that both oral corticosteroids (OCS) and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) increased the fracture risk in COPD; however, after adjusting for differences in disease severity, only OCS posed a significant risk.

The predisposing factors for osteoporosis and fractures in COPD include

- COPD as a disease itself;

- age;

- poor physical activity (related to the inability of COPD patients to engage in activity and skeletal musculo-dysfunction);

- smoking;

- poor nutrition;

- low body mass index (BMI);

- systemic inflammation; and,

- high dose of ICS as well as courses of OCS for exacerbations.

Osteoporosis may remain inconspicuous for some time, becoming evident only when fractures happen. While considerable pain and disability may occur as a consequence of many vertebral fractures, even asymptomatic ones may restrain the respiratory capacity due to wedging and kyphosis of the thoracic spine, which, in a patient with COPD, could further compromise the respiratory function.

Occurrence of fractures has implications for morbidity and mortality. Severe osteoporosis with thoracic vertebral fractures and wedging with hyperkyphosis was associated with about 10% reduction in the forced vital capacity (FVC) in females, with a cumulative effect of the number of fractures on the decline in the FVC. Such a reduction in the FVC would contribute to lung function impairment and disability in patients with chronic lung disease. In the elderly, mortality after hip fractures is approximately 20% in the first year (highest mortality rate for any fractures) and out of these patients, 19% require residential care after discharge from the hospital, adding to the economic burden of the disease. Fragility fractures of the rib may induce hypoventilation and reduce sputum evacuation, which may lead to, or provoke, exacerbations.

Taking into consideration the adverse impact on the lungs and otherwise, early recognition of osteoporosis is essential to ensure the implementation of effective preventive and treatment measures.

Screen the following high-risk patients at baseline by measuring the BMD:

- Men and women with a significant smoking history

- Those with moderate-to-very severe COPD

- Those on low-to-medium dose ICS along with frequent courses of OCS or on high-dose ICS

- Postmenopausal women

- Premenopausal women with amenorrhoea

- Hypogonadal men

- History of fracture

- BMI <21

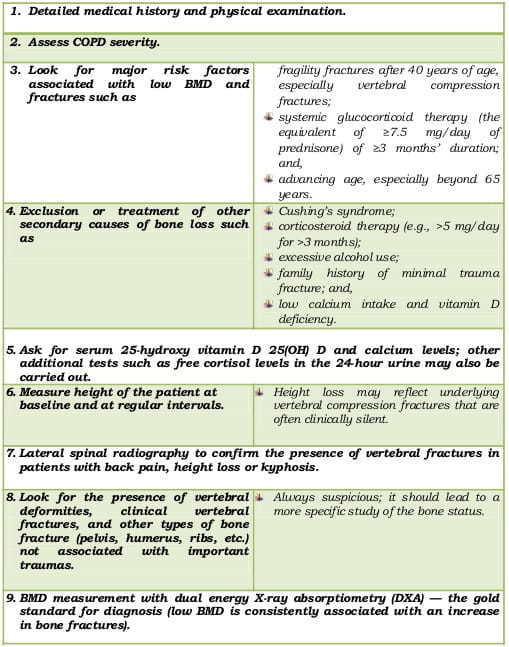

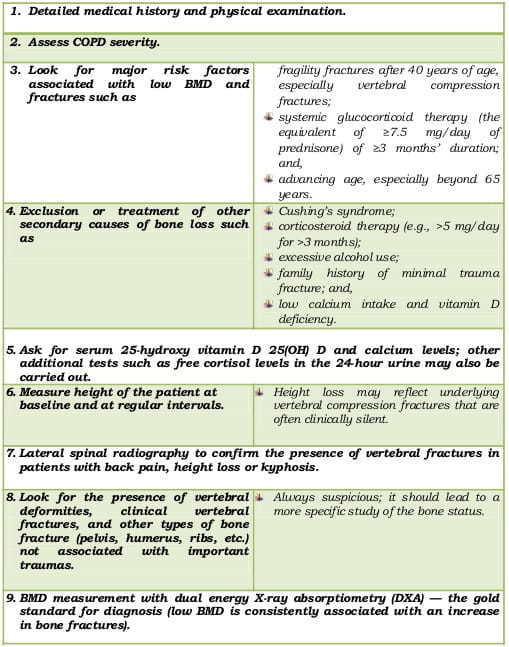

This must include the following:

Table 2: Initial evaluation of high-risk patients

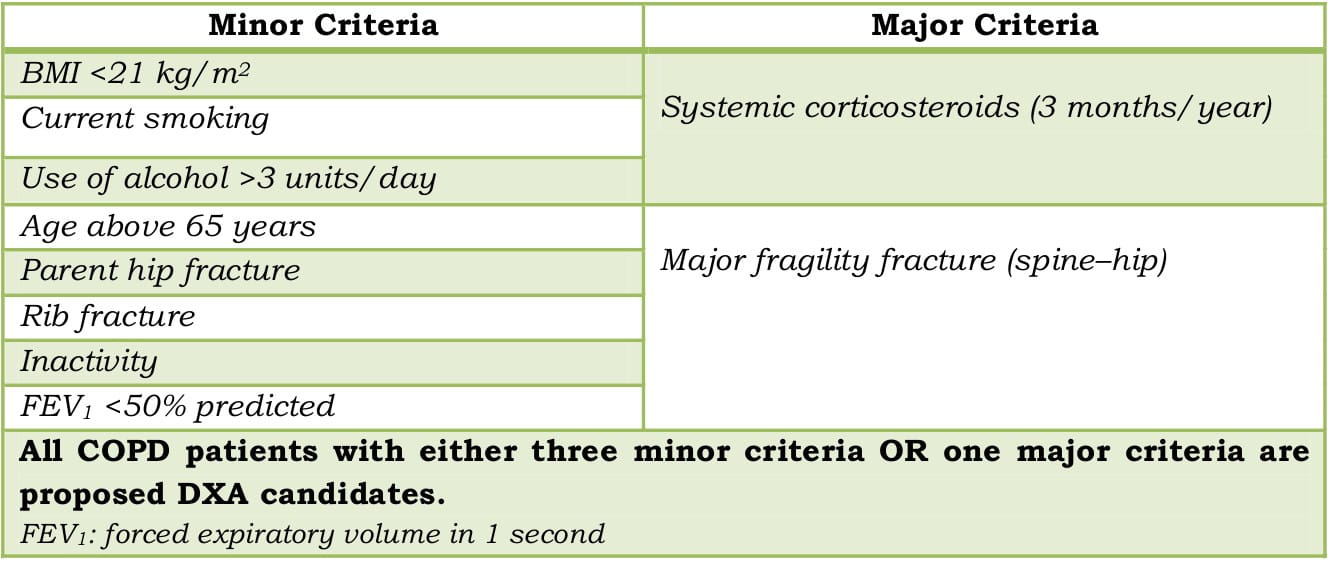

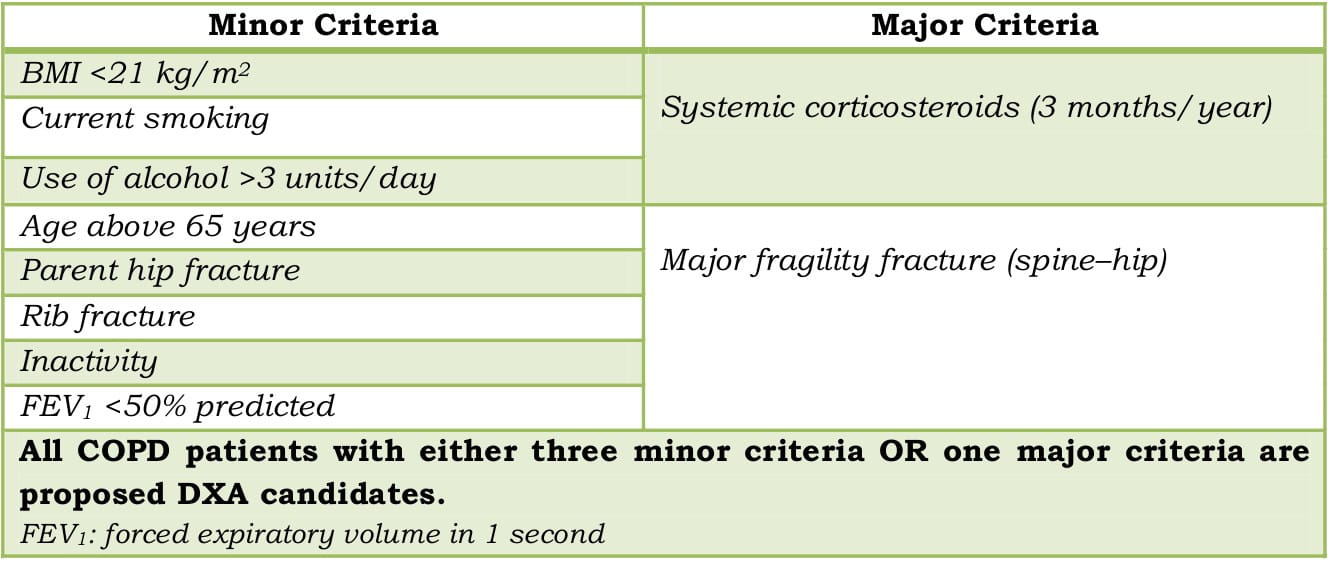

Identifying Candidates for DXA to Measure BMD

Table 3: Criteria for identifying DXA candidates

- DXA of the lumbar spine and the hips along with an investigation of vertebral deformities, using a spinal X-ray.

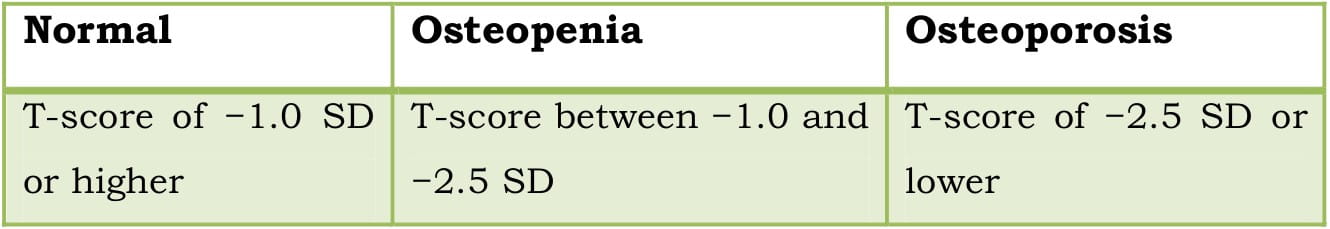

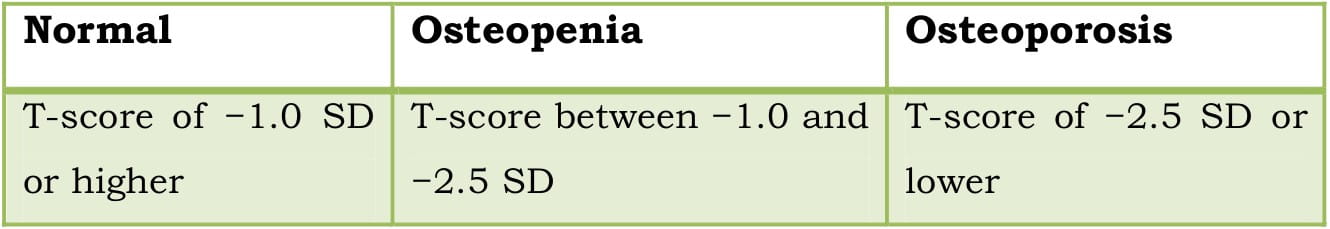

- The lowest T-score of these locations should be used to diagnose osteoporosis, check against the diagnostic categories of BMD, according to the World Health Organization (WHO)

Table 4: Diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis

SD: Standard Deviation

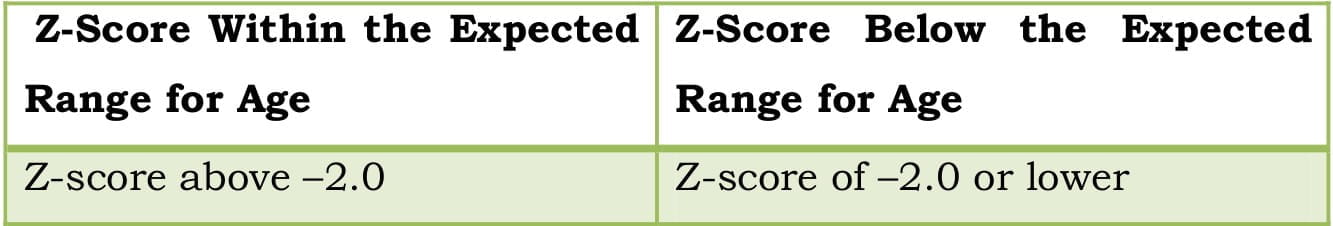

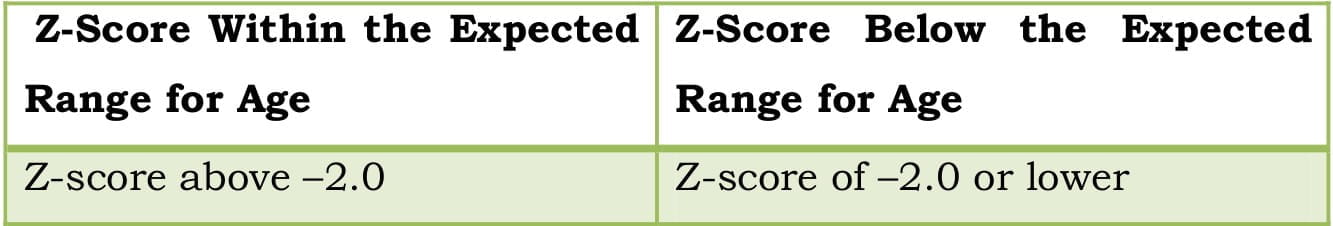

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) guideline states that in premenopausal women, men less than 50 years of age, and children, the WHO BMD diagnostic classification should not be applied. In these groups, the diagnosis of osteoporosis should not be made on the basis of densitometric criteria alone. The International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) recommends that instead of T scores, ethnic or race adjusted Z-scores should be used.

Table 5: Z-score range for premenopausal women and men less than 50 years of age

”T-scores are preferred for reporting the BMD in postmenopausal women and in men aged 50 years and older whereas Z-scores are preferred in females prior to menopause and in males younger than 50 years of age.”

Note:

BMD measurement should ideally be done in all patients starting with OCS, but at least in those who

- start OCS with a daily dose of at least 5 mg for at least 3 months; and,

- need at least one course of OCS yearly.

Although the BMD assessment is specific, it may not be sensitive for predicting the risk of fracture. For this reason, subjects with a reduced BMD may not necessarily have an augmented risk of fracture. Adding clinical risk factors that are able to predict fracture independent of BMD may improve our ability to predict fracture risk. In this case, use of the WHO fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX; http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/) may prove to be a valuable supplement to the BMD assessment.

Introduced by a WHO task force in 2008, FRAX is an algorithm that estimates (calculates) the 10-year absolute fracture risk in individual patients for hip fractures or major osteoporotic fractures (hip, wrist, humerus and clinical spine), using the femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) and easily obtainable clinical risk factors for fracture.

It comprises of the following risk factors: age, prior fracture, parental history of hip fracture, low body weight or BMI, use of OCS of 5 mg or more for 3 months or more, rheumatoid arthritis, current cigarette smoking, excessive alcohol intake of 3 units or more daily (three medium glasses of wine or three half-pints of beer), and secondary osteoporosis.

- FRAX may be used to help decide as to which patients may require prolonged treatment to reduce the risk of future fractures.

- 5 years if no risk factors or using corticosteroid therapy.

- 2 years or more to follow loss of BMD or treatment effect.

- 1 year if using OCS without anti-resorptive therapy.

”An important aspect of COPD treatment should be to avoid bone loss and fragility fractures.”

Little impetus is directed towards screening and/or preventive or management strategy, considering the dearth of symptoms, by and large, prior to a fracture. An important aspect of COPD treatment should be to avoid bone loss and fragility fractures. This involves lifestyle changes, treatment to allow for increased physical activity, keeping OCS/ICS exposure as low as possible, and calcium and vitamin D and anti-resorptive therapy.

There are no specific guidelines on the management of osteoporosis in COPD, but universal recommendations are given below:

- Smoking cessation.

- Counselling on preventing falls (checking vision, installing grab bars in bathroom, proper lighting of bathroom, removing loose wires or toys from floor).

- Avoid excessive intake of alcohol.

- Weight-bearing and strengthening exercises such as walking, jogging, stair climbing, dancing, and tennis.

- Adequate intake of calcium [e.g., milk and milk products, finger millet (ragi/nachni)] and vitamin D (e.g., cod liver oil, sunlight).

- Maintain weight if not overweight.

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programmes in moderate-to-severe disease.

- Long-acting bronchodilators in all patients where airway obstruction might limit the level of physical activity.

- ICS or ICS/long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) or long-acting anticholinergics in severe COPD in order to reduce the frequency of exacerbations.

- During maintenance therapy: Use of ICS in moderate doses, e.g., 500 mcg of Fluticasone propionate per day or equivalent.

- During exacerbations: Dependent on the individual patient:

- Lower OCS dose (30 mg prednisolone for 7 to 8 days).

- High-dose ICS/LABA after one dose of prednisolone 30 mg, e.g.,400/12 mcg Budesonide/Formoterol q.i.d. has been reported in a study

When to consider?

- In everyone aged 50 years or more.

- When starting with OCS or high-dose ICS.

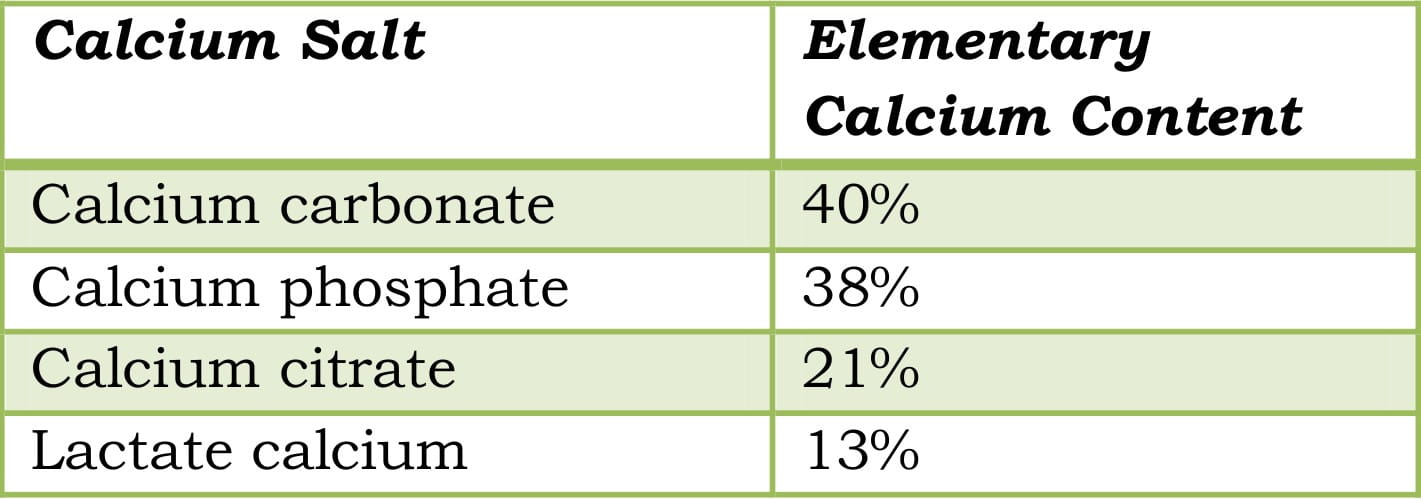

The NOF supports the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recommendation that women aged over 50 years consume at least 1,200 mg per day of elemental calcium. Intakes in excess of 1,200 to 1,500 mg per day have limited potential for benefit and may increase the risk of developing kidney stones or cardiovascular disease.

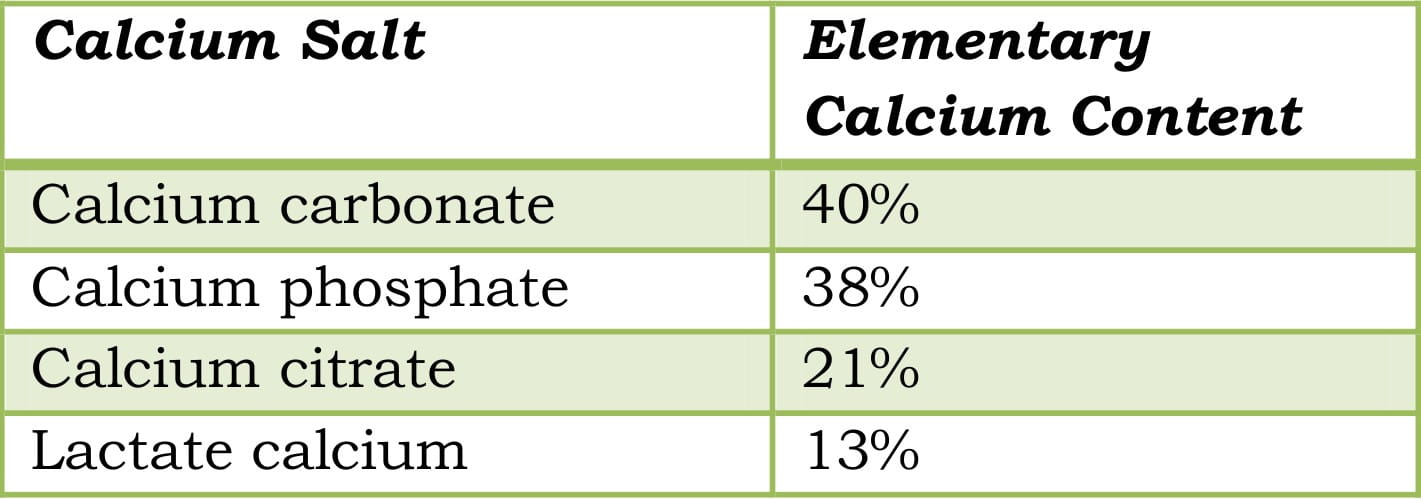

The dosage of the calcium salts depends on the elementary calcium content.

Table 6: Elementary calcium content of calcium salts

Some of the most common calcium salts are calcium citrate malate and calcium carbonate. However, calcium citrate malate has some benefits over calcium carbonate such as the highest bioavailability of 41%, and that it can be taken on an empty stomach, unlike calcium carbonate, and has fewer side effects.

Coral calcium supplements are another option, albeit expensive. Coral calcium is a form of calcium carbonate that also contains magnesium and trace minerals such as selenium and chromium.

Serum 25(OH)D levels should be measured in patients at risk of deficiency and vitamin D supplemented in amounts sufficient to bring the serum 25(OH)D level to 30 ng/ml (75 nmol/L) or higher. Many patients, including those with malabsorption, will need more. The safe upper limit for vitamin D intake for the general adult population was set at 2,000 IU per day earlier; recent evidence indicates that higher intakes are safe and that some elderly patients will need at least this amount to maintain optimal 25(OH)D levels. NOF recommends an intake of 800 to 1,000 IU of vitamin D3 per day for adults over the age of 50 years.

In patients with nephrolithiasis requiring calcium supplements:

In case of patients with nephrolithiasis requiring calcium supplements, there is evidence to suggest that calcium supplementation may be safe if attention is paid to preparation and, especially, to the timing. Calcium supplementation is likely to be safest when taken with meals. Calcium citrate appears to be a more stone-friendly calcium supplement because citrate provides an additional inhibitor action.

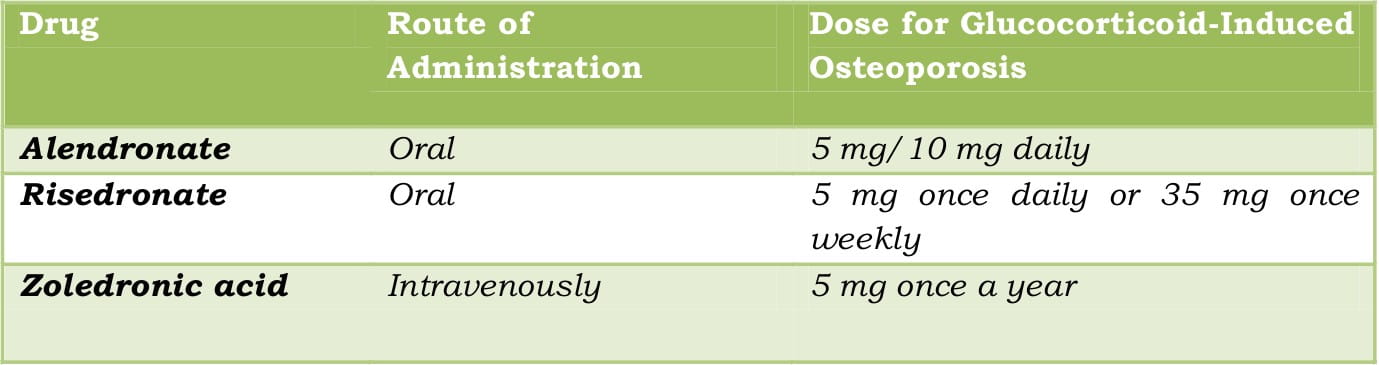

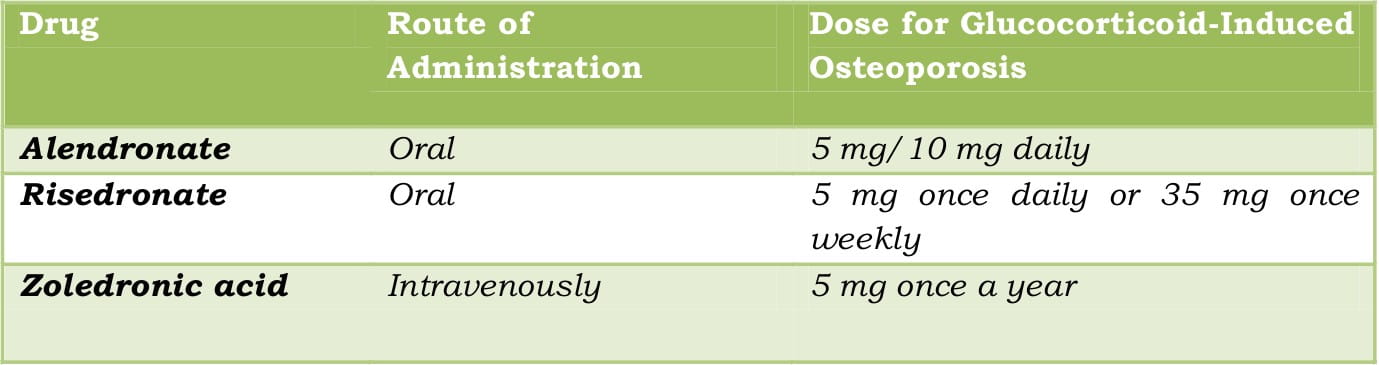

Extensively used for osteoporosis, bisphosphonates have a high affinity for bone mineral and impair bone resorption by blocking key enzymes of osteoclasts.

When to consider?

- If the daily dose of corticosteroids is ≥5 to 7.5 mg and T-score less than -1.

- If yearly cumulative dose of corticosteroids is >800 mg prednisolone.

- If previous fragility fracture and T-score <-2.5 if no use of corticosteroids.

There are several bisphosphonates available for the management of osteoporosis such as alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate (for post- menopausal osteoporosis) and zoledronic acid. The frequency of the dosing regimen may vary ranging from once a day to once a year.

Table 7: Dosage regimen of common drugs for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

Intravenous zoledronic acid can be given once every year, taking care of the poor compliance associated with bisphosphonates. Though there are not many head-to-head trials to compare the efficacy of these bisphosphonates, zoledronic acid can be considered the best as, over 3 years, it reduces the incidence of spine fractures by 70%, hip fractures by 41%, and non-vertebral fractures by 25%.

Taking into account that bisphosphonates may cause hypocalcaemia, adequate calcium and vitamin D supplementation should be done. All patients on bisphosphonate therapy should have the need for continued therapy re-evaluated on a periodic basis.

Bisphosphonates have been reported to be the most effective of evaluated agents for managing CS-induced osteoporosis, with the effect enhancing further by concomitant use of vitamin D and calcium.

Bisphosphonates may be given in combination with calcium and vitamin D supplements for better compliance and adherence to the therapeutic regimen. Risedronate in a combination pack with calcium and vitamin D is already available in the market (Risofos Kit).

Calcitonin salmon may be given via injection or as a nasal spray. Injectable calcitonin is used to treat osteoporosis. The nasal spray is used to treat osteoporosis in women who are at least 5 years past menopause and cannot or do not want to take oestrogen products. The recommended regimens for post- menopausal osteoporosis are 100 units per day injected into the muscle or under the skin or 1 spray (200 units) per day, administered in alternate nostrils.

When to consider?

- In hypogonadal premenopausal women exposed to corticosteroids.

Bisphosphonates are all anti-resorptive agents or anti-catabolic, whereas parathyroid hormone analogues such as teriparatide are anabolic.

When to consider?

- In corticosteroid users with a high risk of fractures*

The recommended dose is 20 mcg subcutaneously once a day. It can be given in the thigh or abdomen, for a maximum of 2 years. Upon the initiation of treatment, patients should be observed for signs and symptoms of orthostatic hypotension. Its route of administration and cost are worth pondering upon.

*People on sustained systemic glucocorticoid therapy (daily dosage equivalent to 5 mg or greater of prednisone), high risk for fracture (defined as a history of osteoporotic fractures, multiple risk factors for fracture or patients who have failed or are intolerant to other available osteoporosis therapy).

In patients with glucocorticoid-induced bone thinning, aged below 65 years without previous fragility fractures:

The guidelines of Royal College of Physicians advocate early intervention by introducing therapy at less severe T-scores than the standard WHO recommendations (2004).

In patients aged over 65 years on OCS:

Therapy is recommended regardless of DXA evaluation, based on the fracture probability in people aged over 65 years on OCS- recommendation is also supported by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines (2004).

To sum up, osteoporosis is a frequently occurring co-morbidity in COPD patients and is not just restricted to those with severe airways obstruction. However, its presence may be masked. Predisposing risk factors such as age, the underlying disease, systemic inflammation and the use of OCS abound in such patients and are likely to be interlinked and may work synergistically. Early detection of osteoporosis in patients with COPD is important with the goals of assessing the risk of fracture and preventing or reducing the same. The management would incorporate the use of pharmacological measures such as anti- resorptive agents, e.g., bisphosphonates or anabolic drugs, e.g., teriparatide in addition to the proper management of COPD (the use of limited corticosteroid doses), as well as non-pharmacological measures such as lifestyle modification and nutritional advice.

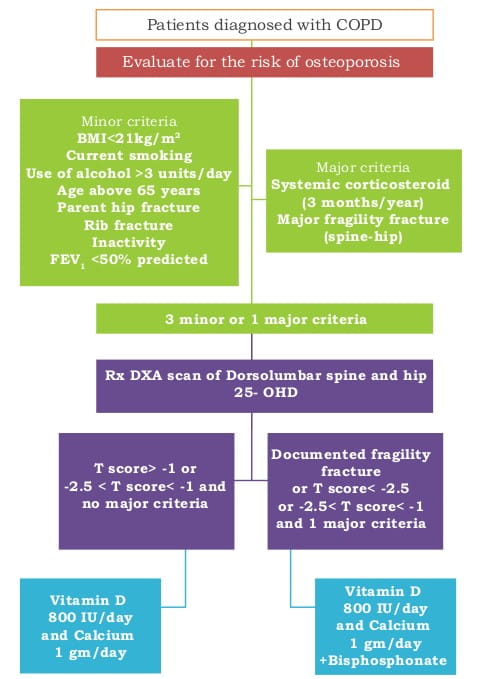

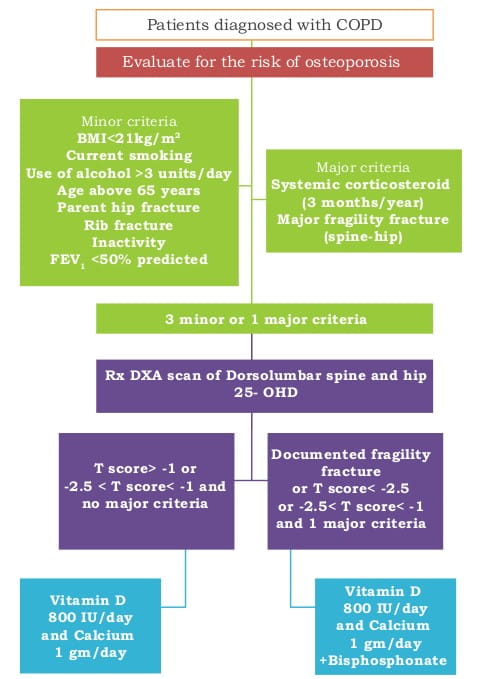

Figure 2: An approach to the management of osteoporosis in patients with COPD

1.Age and Ageing 2006; 35:33-37

2.Campbell-Walsh Urology book, Ninth Edition, Volume 2; 1129- 1888

3.Chest 2002; 121:609-620

4.Chest 2011; 139:648-657

5.Curr Opin Pulm Med 2008; 14:122-127

6.Eur Respir J 2003; 22: Suppl. 46, 64s-75s

7.Eur Respir J 2009; 34:209-218

8.Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009; 4:365-380

9.ISRN Rheumatology 2011, Article ID 901416, doi:10.5402/2011/901416

10.Lung India 2011; 28:184-6

11.National Osteoporosis Foundation, Clinician-s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis, 2008

12.Osteoporos Int. 2009; 20:989-98

13.P & T 2003; 28:713-716

14.Prim Care Respir J 2010; 19:326-334

15.Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008; 5:549-558

15.Respir Med 2009; 103:1143-1151

16.Respir Med: COPD update 2007; 3:135-151

18.Respir Med: COPD update 2009; 5:14-20

19.Respir Res. 2009; 10:11

.svg?iar=0&updated=20230109065058&hash=B8F025B8AA9A24E727DBB30EAED272C8)