HMS: Antiretroviral-based Prevention Strategies in HIV

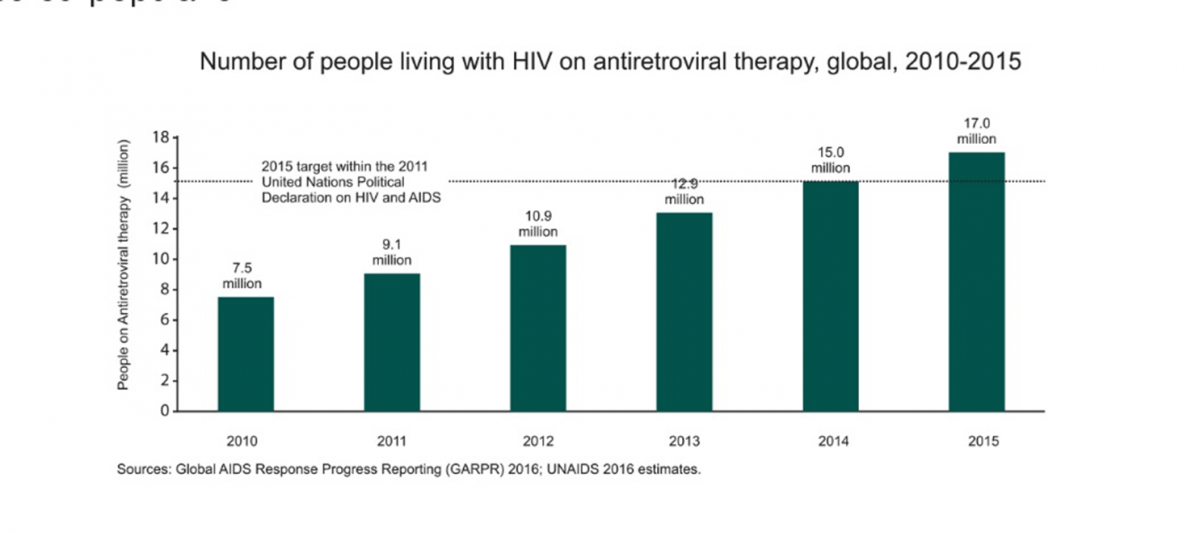

The UNAIDS 2016 Global AIDS Update reported that the global coverage of ART has reached 46%. Eastern and Southern Africa experienced the largest gains, where coverage increased from 24% in 2010 to 54% in 2015. Annual number of new infections among adults remained stable at about 1.9 million as of 2015.Eastern and Southern Africa witnessed a 4% decline in adult HIV infections since 2010.1

Currently, 17 million people are receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART). ART has played a major role in curbing the morbidity and mortality rates in the HIV-infected population.1

However, despite the impressive scale-up of ART and a decline in incidence, HIV continues to remain one of the crucial challenges in many parts of the world. HIV is the leading cause of death in Sub-Saharan Africa, the leading cause of death among women of reproductive age, the third leading cause of death in low-income countries, and the sixth leading cause of death worldwide.2

Thus, preventing new HIV infections remains one of the world’s most important health priorities. Along with the existing prevention methods like post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), preventing mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and use of condoms, newer preventive strategies are gaining attention. These include use of newer technologies (microbicides, multipurpose preventive technologies (MPTs), circumcision techniques, etc.) and novel applications of existing antiretroviral drugs for treatment (e.g. oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)), and, ‘treatment as prevention (TasP)’ to prevent new HIV infections. New bio-medical interventions have been shown to be effective in preventing HIV transmission.3

In addition to the proven role of antiretrovirals (ARVs) in treatment, they also play an important role in prevention. ARVs can be used to prevent HIV transmission in one of the following ways:4

- Before exposure

- as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)

- as treatment of infected people for secondary prevention, such as Treatment as Prevention (TasP)

- as preventing mother-to-child transmission strategies (PMTCT)

- After exposure

- as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP)

Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

Introduction

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection is a strategy where ARVs are administered to HIV-negative individuals who are at high risk of HIV acquisition to decrease the risk of establishment of HIV infection.5

Data from Clinical Trials

Several clinical trials have demonstrated safety and a substantial reduction in the rate of HIV acquisition with the use of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)/emtricitabine (FTC) or TDF as PrEP in the high-risk populations.6 The following table is a summary of the efficacy trials for the use of PrEP in various high-risk populations:

|

Study (participants) |

Design |

Outcomes |

Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

|

iPrEx Study7 (Men who have sex with men (MSM)) |

Phase 3 TDF/FTC OD (n=1,251) and Placebo (n=1,248) |

100 became infected during follow-up

36 in the TDF/FTC group, indicating a 44% reduction in the incidence of HIV (P=0.005) |

Oral TDF/FTC provided protection against the acquisition of HIV infection among HIV-seronegative men or transgender women who have sex with men. Nausea was reported more frequently during the first 4 weeks in the TDF/FTC group. |

|

Partners PrEP8 (Heterosexual Men and women) |

Phase 3 TDF OD (n=1,584) TDF/FTC OD (n=1,579) and Placebo (n=1,584) |

82 HIV-1 infections occurred in seronegative participants: · 17 in the TDF group (67%) · 13 in the TDF/FTC group (75%) (P<0.001)

|

Oral TDF and TDF/FTC both protect against HIV-1 infection in heterosexual men and women. Rate of serious adverse events was similar across the groups. |

|

TDF29 (Heterosexual Men and women) |

Phase 2 TDF/FTC OD (n=611) Placebo (n=608) |

33 participants who became infected : 9 in the TDF / FTC group. The efficacy of TDF/FTC was 62.2% (P=0.03). |

Daily TDF/FTC prophylaxis prevented HIV infection in sexually active heterosexual adults. |

|

Bangkok Tenofovir Study (BTS)10 (Injecting Drug Users) |

Phase 3 TDF OD (n=204) Placebo (n=209) |

50 became infected during follow-up: 17 in the TDF group 33 in the placebo group, Indicating a 48.9% reduction in HIV incidence. (P=0.01) |

Daily oral tenofovir reduced the risk of HIV infection in people who inject drugs. |

|

PROUD study11 (MSM) |

TDF/FTC OD initiated immediately (IMM, n= 276) TDF/FTC OD deferred for 12 months and then followed quarterly (DEF, n=269) |

3 HIV infections in IMM group (1.3/100 PY) and 19 infections in DEF group (8.9/100 PY) Yielding a rate difference of 7.6/100 PY. Indicating a reduction of 86% in HIV incidence (P=0.0002) |

Daily TDF/FTC conferred impressive protection against HIV in the high-risk MSM group. |

|

IPERGAY study12 (high-risk MSM) |

Participants were asked to take two pills of TDF/FTC (300 mg/ |

The incidence of HIV-infection in the TDF/FTC group was 0.94 per 100 PY, indicating a relative reduction of 86% in the incidence of HIV with on demand PrEP. (P=0.002)

|

On demand PrEP with oral TDF/FTC is highly effective to reduce the incidence of HIV-infection in high-risk MSM and has a good safety profile. Gastrointestinal adverse events (nausea, diarrhoea, abdominal pain) were reported more frequently with TDF/FTC. |

PY: Patient-years

HPTN 067/ADAPT Study13

The outcomes of the HPTN 067/ADAPT study were reported at the IAS 2015 conference. The study was a trio of three Phase II randomized, open-label PrEP trials, investigating the feasibility and acceptability of different PrEP regimens among men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women (TGW), and women having sex with men (WSM) in Bangkok (MSM/TGW), Harlem (New York (MSM/TGW)) and Cape Town (WSM).

The trial participants were randomized (1:1:1) to receive one of the following three PrEP regimens, i.e. either a daily dose of TDF/FTC (D arm), or twice-weekly dose of TDF/FTC + an extra dose after sex (T arm), or an event-driven dosing [one dose up to 48 hours before sex, another 2 hours after sex (E arm)]. The participants were followed for six months. Adherence and coverage were assessed using electronic monitoring adjusted by self-reported sex and pill-taking behaviour collected in detailed weekly interviews.

Adherence in the above studies was as follows

|

Sites |

Arms |

||

|

D Arm |

T Arm |

E Arm |

|

|

Bangkok |

85% |

79% |

65% |

|

Harlem |

65% |

46% |

41% |

The primary analysis was of the percentage of reported sexual acts that were protected by PrEP, with doses both before and after sex.

- In Bangkok, PrEP coverages were similar in arms D and T (85% vs 84%, p=0.79) and both were greater than in arm E (74%) (p<0.05).

- In Harlem, the daily regimen protected 66% of sexual acts, the twice-weekly regimen protected 47%, and the event-driven regimen protected 52%.

- In Cape Town, the daily regimen protected 75% of sexual acts, the twice-weekly regimen protected 56%, and the event-driven regimen protected 52%.

Also, it was observed that over 90% of participants from Bangkok, in each arm, had detectable drug, with no significant differences between arms. Comparatively, in Harlem and Cape Town, participants were more likely to have detectable drug if they were taking daily PrEP dosing.

There was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of side effects between arms. Gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms (dizziness, headaches, nausea, diarrhoea, etc.) reported were mild and mostly experienced during the first two months of taking PrEP. The non-daily regimens required the use of considerably fewer tablets compared to daily dosing, which could make providing PrEP more affordable.

The studies demonstrated the following

- The feasibility of intermittent PrEP, as a, potentially, more cost-effective alternative to daily PrEP, among US Black MSM in Harlem.

- Time-driven dosing regimen was found to offer comparably high PrEP coverage for sex acts among Thai MSM, despite slightly less adherence, while requiring fewer tablets.

- The daily dosing resulted in higher coverage of sex events, higher drug concentrations, and higher adherence among women in Cape Town.

US Demo Project14

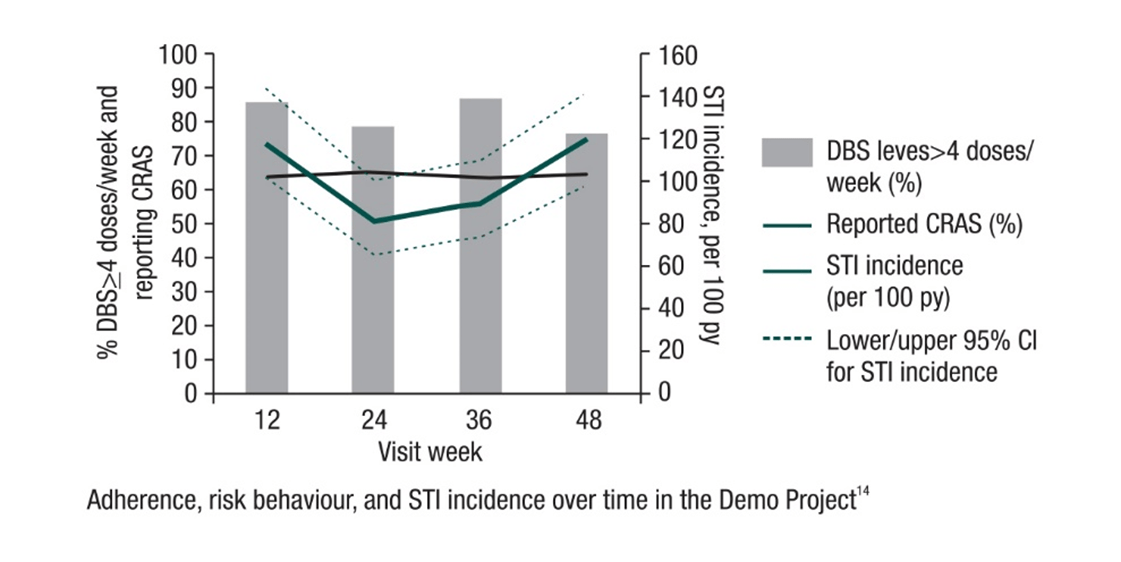

The first US multi-site, open-label Demo Project was conducted to assess PrEP delivery in municipal STD (San Francisco, Miami) and community-health (Washington, DC) clinics.

Investigators enrolled 557 HIV-uninfected MSM/TGW from 9/2012-1/2014. They were offered 48 weeks of PrEP. Tenofovir-diphosphate levels were measured in dried blood spots (DBS) in a random sample of participants (pts). Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess correlates of adherence. Sexual behaviours, PrEP discontinuations, and HIV/sexually transmitted infection (STI) incidence were also described.

Among 147 pts with DBS testing, 65% had drug levels consistent with taking ≥4 doses/week at all visits, 3% always had DBS levels <2 doses/week, and 32% had an inconsistent pattern.

Black patients, being self-referred to the PrEP programme, and having a greater number of condomless anal sex (AS) partners were independently associated with DBS ≥4 doses/week (all p<0.05). There was a decline observed in the past 3 months in the number of AS partners, from baseline to week 48 (P<0.0008). Condomless receptive AS (CRAS) reported by two-thirds of the population at baseline was found to be stable during follow-up (p=0.96).

PrEP was discontinued by 20 patients due to low self-perceived HIV risk and 65% of these pts reported CRAS in the prior 3-6 months. The incidence of STI was found to be high; however, it did not increase over time (p=0.87). Overall, 27.5% had early syphilis, GC, or CT at screening, and 38% had ≥1 STI during follow-up.

The Demo Project

demonstrated high adherence to PrEP among the study population. Also, HIV incidence was low in this cohort at

ongoing high sexual risk for HIV. The incidence of STIs was found to be high during PrEP use, thus screening for and

treatment of STIs remains important.

The Demo Project

demonstrated high adherence to PrEP among the study population. Also, HIV incidence was low in this cohort at

ongoing high sexual risk for HIV. The incidence of STIs was found to be high during PrEP use, thus screening for and

treatment of STIs remains important.

Recommended Regimen for PrEP

The fixed-dose combination of TDF/FTC as a single daily dose is currently the only US FDA approved combination for PrEP in healthy adults (HIV-uninfected) at risk of acquiring HIV infection.

Dosage: TDF/FTC (300 mg/200 mg) once a day.

WHO Recommendations15

- The WHO recommends oral PrEP for preventing the acquisition of HIV infection as follows:

‘Oral PrEP containing TDF should be offered as an additional prevention choice for people at substantial risk of HIV infection as part of combination HIV prevention approaches’.

WHO has also defined the term of ‘Substantial risk’ as follows:

Substantial risk of HIV infection is provisionally defined as HIV incidence greater than 3 per 100 person–years in the absence of PrEP. HIV incidence greater than 3 per 100 person–years has been identified among some groups of men who have sex with men (MSM), transgender women (TGW) in many settings and heterosexual men and women who have sexual partners with undiagnosed or untreated HIV infection. Individual risk varies within groups at substantial risk depending on individual behaviour and the characteristics of sexual partners.

CDC Recommendations6

The CDC guidelines recommends the use daily oral antiretroviral PrEP to reduce the risk of acquiring HIV infection in adults. TDF/FTC is recommended as one of the prevention options for the following adult populations who are at substantial risk of HIV acquisition:

- sexually-active adult MSM

- heterosexually active men and women

- injection drug users (IDU)

- heterosexually-active women and men whose partners are known to have HIV infection (i.e., HIV-serodiscordant couples) as one of several options to protect the uninfected partner during conception and pregnancy so that an informed decision can be made in awareness of what is known and unknown about the benefits and risks of PrEP for the mother and the fetus.

Country Updates49

In India, Cipla has received Regulatory approval for the use of Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) for PrEP. Other countries that have approved (TDF/FTC) for PrEP as of June 2016 are as follows:

• USA • Peru

• France • South Africa

• Canada • Australia

• Kenya • Israel

Clinicians Initiating the Provision of PrEP6

Clinicians initiating PrEP should do the following:

- Prescribe medication regimens that are proven safe and effective for uninfected persons who meet recommended criteria to reduce their risk of HIV acquisition.

- Educate patients about the medications and the regimen to maximize their safe use.

- Provide support for medication-adherence to help patients achieve and maintain protective levels of medication in their bodies.

- Provide HIV risk-reduction support and prevention services or service referrals to help patients minimize their exposure to HIV.

- Provide effective contraception to women who are taking PrEP and who do not wish to become pregnant.

- Monitor patients to detect HIV infection, medication toxicities, and levels of risk behaviour in order to make indicated changes in strategies to support the patients’ long-term health.

These goals have been framed by the CDC to reduce the HIV-associated morbidity, mortality and costs to individuals and society.

Clinical Follow-up and Monitoring6

Once PrEP is initiated, patients should return for follow-up approximately every 3 months. Clinicians may wish to see patients more frequently at the beginning of PrEP (e.g., 1 month after initiation), to assess and confirm HIV-negative test status, assess for early side effects, discuss any difficulties with medication adherence, and answer questions.

All patients receiving PrEP should be seen as follows:

At least every 3 months to

- Repeat HIV testing and assess for signs or symptoms of acute infection to document that patients are still HIV negative.

- Repeat pregnancy testing for women who may become pregnant.

- Provide a prescription or refill authorization of daily TDF/FTC for no more than 90 days (until the next HIV test).

- Assess side effects, adherence, and HIV acquisition risk behaviours.

- Provide support for medication adherence and risk-reduction behaviours.

- Respond to new questions and provide any new information about PrEP use.

At least every 6 months to

- Monitor eCrCl

- If other threats to renal safety are present (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), renal function may require more frequent monitoring or may need to include additional tests (e.g., urinalysis for proteinuria).

- A rise in serum creatinine is not a reason to withhold treatment if eCrCl remains ≥60 ml/min.

- If eCrCl is declining steadily (but still ≥60 ml/min), consultation with a nephrologist or other evaluation of possible threats to renal health may be indicated.

- Conduct STI testing recommended for sexually active adolescents and adults (i.e., syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia).

At least every 12 months to

- Evaluate the need to continue PrEP as a component of HIV prevention.

Drug Interactions with TDF/FTC6

|

|

TDF |

FTC |

|

Buprenorphine |

No significant effect. No dosage adjustment necessary. |

No data |

|

Methadone |

No significant effect. No dosage adjustment necessary. |

No data |

|

Oral contraceptives |

No significant effect. No dosage adjustment necessary. |

No data |

|

Acyclovir, valacyclovir, cidofovir, ganciclovir, valganciclovir, aminoglycosides, high-dose or multiple NSAIDs or other drugs that reduce renal function or compete for active renal tubular secretion |

Serum concentrations of these drugs and/or TDF may be increased. Monitor for dose-related renal toxicities. |

No data |

Medications Not To Be Used6

Only daily oral dose of TDF/FTC is approved, daily dose of TDF alone as an alternative only for IDU and heterosexually active adults could be used. The following needs to be kept in mind while prescribing PrEP therapy:

- Do not use other antiretroviral medications (e.g., 3TC), either in place of, or in addition to, TDF/FTC or TDF.

- Do not use other than daily dosing (e.g., intermittent, episodic [pre/post sex only], or other discontinuous dosing).

- Do not provide PrEP as expedited partner therapy (i.e., do not prescribe for an uninfected person not in your care).

Side Effects6

Patients taking PrEP should be informed of side effects among HIV-uninfected participants in clinical trials. In these trials, side effects were uncommon and usually resolved within the first month of taking PrEP (‘start-up syndrome’).

Clinicians should discuss the use of over-the-counter medications for headache, nausea, and flatulence should they occur.

Patients should also be counselled about signs or symptoms that indicate a need for urgent evaluation (e.g. those suggesting possible acute renal injury or acute HIV infection).

Discontinuing PrEP6

- Patients may discontinue PrEP medication for several reasons like:

– personal choice

– changed life situations resulting in lowered risk of HIV acquisition

– intolerable toxicities

– chronic non-adherence to the prescribed dosing regimen despite efforts to improve daily pill-taking

– acquisition of HIV infection

- Upon discontinuation for any reason, the following should be documented in the health record:

– HIV status at the time of discontinuation

– reason for PrEP discontinuation

– recent medication adherence and reported sexual risk behavior

Other Considerations

Women who become pregnant or breastfeed while taking PrEP medication6

PrEP use periconception and during pregnancy by the uninfected partner may offer an additional tool to reduce the risk of sexual HIV acquisition.

Patients with chronic active HBV infection:6

- TDF and FTC are each active against both HIV infection and HBV infection and thus, may prevent the development of significant liver disease by suppressing the replication of HBV.

- Patients should be tested for HBV DNA by the use of a quantitative assay to determine the level of HBV replication before PrEP is prescribed and every 6-12 months while taking PrEP.

Patients with chronic renal failure6

HIV-uninfected patients with chronic renal failure, as evidenced by an eCrCl of <60 ml/min, should not take PrEP because the safety of TDF/FTC for such persons was not evaluated in the clinical trials.

Adolescent Minors6

Clinicians considering providing PrEP to a person under the age of legal adulthood (a minor):

- should be aware of local laws, regulations, and policies

- lack of data on safety and effectiveness of PrEP taken by persons under 18 years of age

- possibility of bone or other toxicities among youth who are still growing; and

- safety evidence available when TDF/FTC is used in treatment regimens for HIV-infected youth

Important to counsel About6

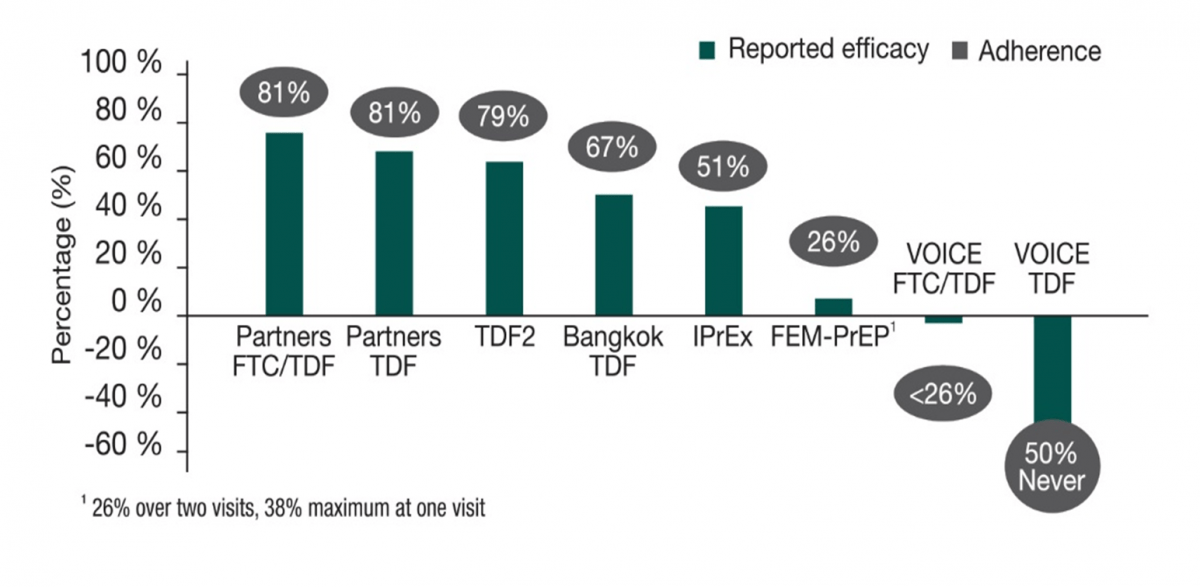

Medication adherence is critical to achieving the maximum prevention benefit and reducing the risk of selecting for a drug-resistant virus if non-adherence leads to HIV acquisition. The following graph shows the impact of low-level adherence on the efficacy in various PrEP trials.

Reducing HIV Risk Behaviours6

The adoption and the maintenance of safer behaviors (sexual, injection, and other substance abuse) are critical for the lifelong prevention of HIV infection and are important for the clinical management of persons prescribed PrEP.

PrEP adherence and PrEP efficacy in key studies16

Overall

Strategy for PrEP Management6

Overall

Strategy for PrEP Management6

|

|

Men Who Have Sex with Men |

Heterosexual Women and Men |

Injection Drug Users |

|

Detecting substantial risk of acquiring HIV infection |

HIV-positive sexual partner Recent bacterial STI High number of sex partners History of inconsistent or no condom use Commercial sex work |

HIV-positive sexual partner Recent bacterial STI High number of sex partners History of inconsistent or no condom use Commercial sex work In high-prevalence area or network |

HIV-positive injecting partner Sharing injection equipment Recent drug treatment (but currently injecting) |

|

Clinically eligible |

Documented negative HIV test result before prescribing PrEP No signs/symptoms of acute HIV infection Normal renal function; no contraindicated medications Documented hepatitis B virus infection and vaccination status |

||

|

Prescription |

Daily, continuing, oral doses of TDF/FTC <90-day supply |

||

|

Other services |

Follow-up visits at least every 3 months to provide the following: HIV test, medication adherence counselling, behaviours risk reduction support, side effect assessment, STI symptom assessment At 3 months and every 6 months thereafter, assess renal function Every 6 months, test for bacterial STIs |

||

|

|

Do oral/rectal STI testing |

Assess pregnancy intent Pregnancy test every 3 months |

Access to clean needles/syringes and drug treatment services |

Conclusion

Antiretroviral prophylaxis has been very effective in preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV and, therefore, there is a great hope that this strategy will prove effective against other routes of HIV transmission. In the absence of an effective vaccine, use of antiretroviral drugs as PrEP might be a reliable intervention to protect high-risk HIV-negative people from infection. Many currently available drugs for treatment also have desirable characteristics and are being analysed for use as PrEP.17

Treatment as Prevention (TasP)

As people are living longer with HIV, a new demographic – ‘the serodiscordant couple’ – has emerged where one partner is HIV positive and the other partner is HIV negative. In these cases, prevention of transmission to the uninfected partner is of utmost importance.

Treatment as prevention (TasP) is a term used to describe HIV prevention methods that use ART in HIV-positive persons to decrease the chance of HIV transmission independent of CD4 cell count.18

ART has been effective in reducing the amount of HIV-1 in genital secretions. Because the sexual transmission of HIV-1 from infected persons to their partners is strongly correlated with concentrations of HIV-1 in blood and in the genital tract, it has been hypothesized that antiretroviral therapy could reduce sexual transmission of the virus. Several observational studies have reported decreased acquisition of HIV-1 by sexual partners of patients receiving ART. 19 The definitive proof for this approach came from the HPTN 052 study, which has been hailed as THE BREAKTHROUGH OF THE YEAR 2011 by the Science Magazine.20

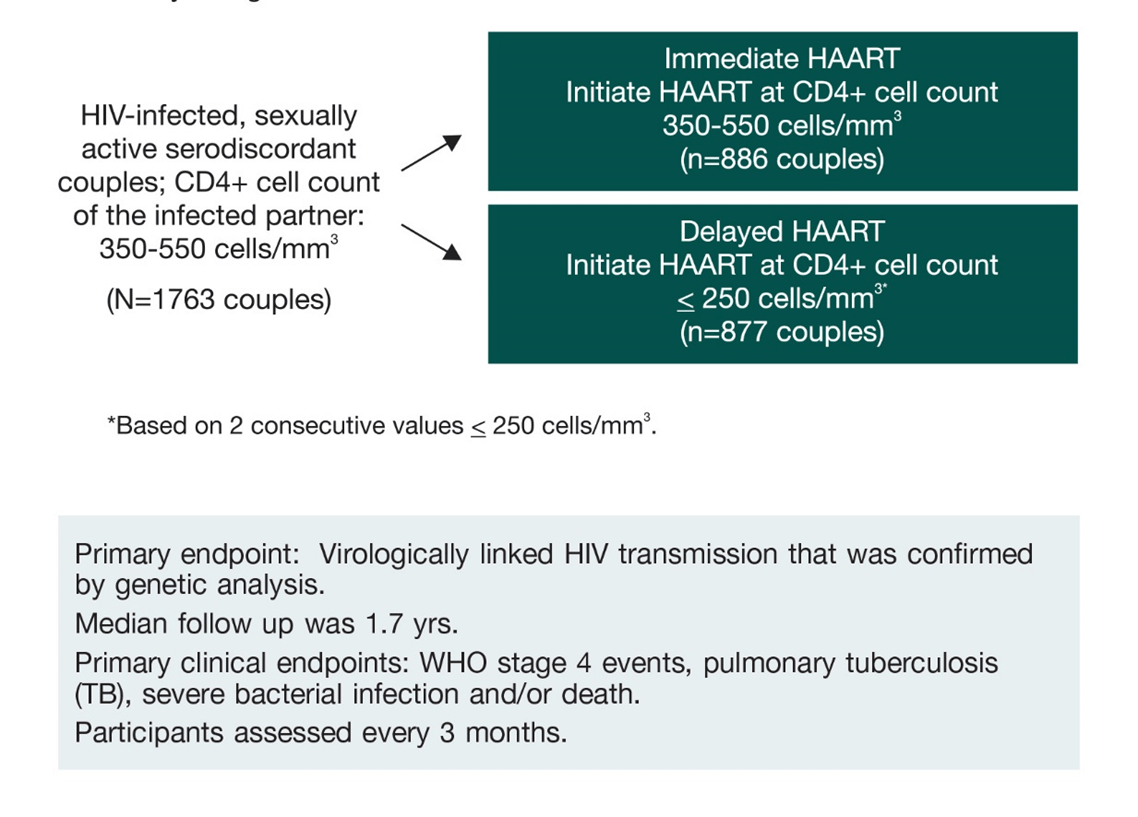

About HPTN 05219, 21

HPTN 052, was designed to evaluate whether immediate versus delayed use of ART by HIV-infected individuals would reduce transmission of HIV to their HIV-uninfected partners and potentially benefit the HIV-infected individual as well. The study was conducted at 13 sites across Africa, Asia and the Americas.

Couples were required to have had a stable relationship for at least 3 months and not have received any previous ART except for short-term prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1.

The study design was as follows:

Key Findings

- Immediate ART in the HIV-infected partner is associated with a 96% reduction in the risk of transmission in serodiscordant couples.

- Total number of HIV-1 transmission events observed were 39, which translates into 96% reduction in the risk of transmission (p<0.0001).

- Statistical significant reduction in the risk of extrapulmonary TB in the early treatment arm: 17 cases occurred in the deferred arm vs 3 in the early treatment arm (p=0.0013).

In the final outcomes of the HPTN 052 trial, it was observed that after ART was offered to index participants in both study arms, there were 2 linked infections in the early arm (15 total infections/2,537 py) and 7 linked infections in the delayed arm (17 total infections/2,412 py). This indicates a 93% reduction in the risk of transmission of HIV among serodiscordant couples.22

Also, there were only 7 linked infections diagnosed while the index participants were receiving ART: 4 infections diagnosed shortly after the index participant started ART and 3 were diagnosed after ART failure. These outcomes showed that HIV transmission is very unlikely when viral replication is suppressed.22

Therefore, the previously reported efficacy of early ART for HIV prevention was sustained for the duration the trial. ART, combined with counselling and provision of condoms provides durable, highly-effective protection from HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples.22

In light of the results of HPTN 052, the WHO and many organizations have formulated recommendations regarding the use of ART for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples.22

Recommendations from various guidelines

|

Guidelines |

Recommendations on TasP |

|

DHHS 201523 |

ART should be offered to patients who are at risk of transmitting HIV to sexual partners |

|

BHIVA 201524 |

The use of ART to reduce transmission risk is a particularly important consideration in serodiscordant heterosexual couples wishing to conceive, and it is recommended that the HIV-positive partner be on fully suppressive ART |

|

EACS 201525 |

Use of ART should also be recommended with any CD4 count in order to reduce sexual transmission |

|

IAS 201426 |

ART is recommended for the treatment of HIV infection and for the prevention of transmission of HIV |

|

WHO 201627,53 |

Initiate ART regardless of WHO clinical stage and CD4 cell count in HIV-positive individual in a serodiscordant partnership (to reduce HIV transmission risk) |

Thus, ART should a be an option available to all serodiscordant heterosexual couples as part of a comprehensive combination prevention strategy.

Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission (PMTCT)

Mother-to-child transmission of HIV can occur either during pregnancy, labour, delivery or breastfeeding. In the absence of any interventions the rate of transmission ranges between 15-45%. This rate can be reduced to levels below 5% with effective interventions.28

Interventions to reduce MTCT:27

- antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the mother and baby

- avoidance of breastfeeding

- alternatively, exclusive breastfeeding and receive antiretroviral

WHO Recommendations for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women27

|

Pregnant and breastfeeding women with HIV |

HIV-exposed infant |

|

|

ART should be initiated in all pregnant and breastfeeding women living with HIV regardless of WHO clinical stage and at any CD4 cell count and continued lifelong |

Breastfeeding |

Replacement feeding |

|

6 weeks of infant prophylaxis with once daily NVP |

4–6 weeks of infant prophylaxis with once-daily NVP or twice-daily AZT |

|

The combination of TDF + 3TC (or FTC) + EFV (once-daily fixed-dose combination) is recommended as first-line ART in pregnant and breastfeeding women, including pregnant women in the first trimester of pregnancy and women of childbearing age. The recommendation applies both to lifelong treatment and to ART initiated for PMTCT and then stopped.

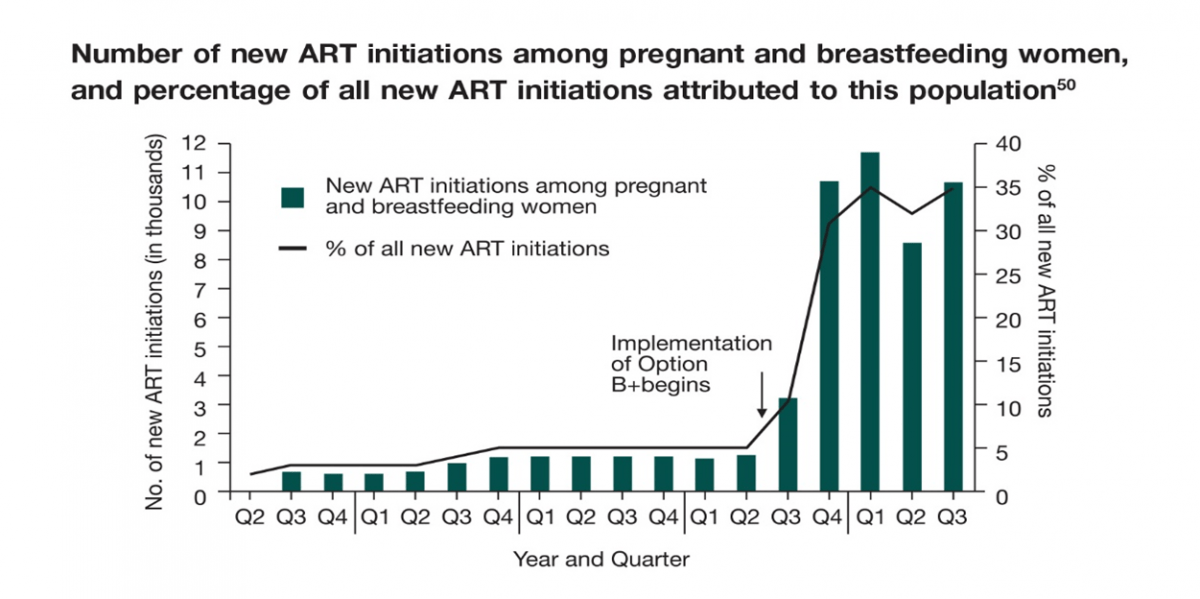

In the third quarter of 2011, the Malawi Ministry of Health (MOH) implemented the ‘Option B+’ and showed a significant impact at the end of the third quarter of 2012, which was summarized in a report. Implementation of Option B+ resulted in a 748% increase in the number of pregnant and breastfeeding women starting ART, from 1,257 in the second quarter of 2011 (representing 5% of all new ART initiations) to 10,663 in the third quarter of 2012 (35% of all new ART initiations).29

Number of new ART initiations among pregnant and breastfeeding women, and percentage of all new ART initiations attributed to this population50

The implementation of Option B+ is shown to have multiple benefits. ART provides protection to HIV-infected women for their own health as well as preventing transmission to their offspring.

Current Status1

In the UNAIDS 2015 report, it was reported that 73% of pregnant women living with HIV received antiretroviral medicines to avoid HIV transmission to their newborns at the end of December 2014. This compares with 36% coverage of effective antiretroviral medicines for prevention of mother-to-child transmission in 2009, reflecting an extraordinary expansion of services that has enabled the world to move towards the goal of eliminating new HIV infections among children.

The number of children newly infected with HIV globally in 2014 was reported to be 220,000 which is less than half the number who acquired HIV in 2000. Since 2,000, antiretroviral medicines have averted an estimated 1.4 million HIV infections among children. The number of new HIV infections among children declined by 27% between 2000 and 2009, and by 41% between 2010 and 2014.1

Therefore, with the rapid expansion of services and efforts to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission, a massive impact has been seen in preventing transmission to children and, in turn, contributing to global efforts to reduce mortality in children.

Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

Preventing exposures to blood and body fluids (i.e. primary prevention) is the most important strategy for preventing acquisition of HIV infection. Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) is the use of short-term ART to reduce the risk of acquisition of HIV infection following exposure. It is widely available following occupational exposure to HIV and has become increasingly available for non-occupational exposure to HIV.30

The updated WHO 201431 and US Public Health Service 201332 guidelines consist of recommendations for the management of persons who experience exposure to blood and/or other body fluids that might contain HIV. It is imperative to follow universal precautions strictly, and consider all patients to be potentially infectious.

Who is Eligible for PEP?31

- PEP should be offered, and initiated as early as possible, to all individuals with exposure that has the potential for HIV transmission, and ideally within 72 hours.a

- Assessment for eligibility should be based on the HIV status of the source whenever possible and may include consideration of background prevalence and local epidemiological patterns.b

- Exposures that may warrant post-exposure prophylaxis include:

- Parenteral or mucous membrane exposure (sexual exposure and splashes to the eye, nose or oral cavity).

- The following bodily fluids may pose a risk of HIV infection: blood, blood-stained saliva, breast-milk, genital secretions and cerebrospinal, amniotic, rectal, peritoneal, synovial, pericardial or pleural fluids.c

- Exposures that do not require post-exposure prophylaxis include:

- When the exposed individual is already HIV-positive.

- When the source is established to be HIV negative.

- Exposure to bodily fluids that does not pose a significant risk: tears, non-blood-stained saliva, urine and sweat.

a Although post-exposure prophylaxis is ideally provided within 72 hours of exposure, people may not be able to access services within this time. Providers should consider the range of other essential interventions and referrals that should be offered to clients presenting after the 72 hours.

b In some settings with high background HIV prevalence or where the source is known to be at high risk for HIV infection, all exposure may be considered for post-exposure prophylaxis without risk assessment.

c These fluids carry a high risk of HIV infection, but this list is not exhaustive and all cases should be assessed clinically and decisions made by the health-care workers as to whether exposure constitutes significant risk.

Knowing the HIV Status

Exposed Person:31

- HIV testing in the context of PEP should include initial testing of the exposed individual with rapid diagnostic tests that can provide definitive results in most cases within 2 hours and often within 20 minutes.

- If the exposed person is already HIV positive – PEP is not indicated and appropriate antiretroviral treatment intervention need to be given as per national ART guidelines.

- In emergency situations where HIV testing and counselling is not readily available but the potential HIV risk is high or if the exposed person refuses initial testing, PEP should be initiated and HIV testing and counselling undertaken as soon as possible.

Source Patient

- Whenever possible, the HIV status of the exposure source patient should be determined to guide appropriate use of HIV PEP.31,32

- Administration of PEP should not be delayed while waiting for test results.31,32

- If the source patient is determined to be HIV-negative:

– PEP should be discontinued, and no follow-up HIV testing for the exposed provider is indicated.31, 32

- If the source patient is determined to be HIV-positive the appropriate treatment and care needs to be given.31

Timing and Duration of PEP

- Occupational exposures to HIV should be considered urgent medical concerns and treated immediately.32

- PEP should be initiated as soon as possible:31,32

– preferably within 72 hours of exposure

– should be continued for a 4-week duration (28-day course)

- If the HIV status of a source patient for whom the practitioner has a reasonable suspicion of HIV infection is unknown and the practitioner anticipates that hours or days may be required to resolve this issue:32

– Antiretroviral medications should be started immediately rather than delayed.

Prescribing and dispensing PEP:31

- PEP can be initiated or dispensed by trained nonphysicians, midwives, nurses and other non-clinical health providers.

- Verbal consent is required.

- Individuals should be made aware of the risks and benefits of PEP, including information on potential drug–drug interactions and possible side effects and toxicity.

- Promoting adherence is critical to improving completion rates.

Recommendations for HIV PEP regimens in adults and adolescents

A regimen for PEP for HIV with two ARV drugs is effective, but three drugs are preferred.

The drug regimen selected for HIV PEP should have a favourable side effect profile, as well as a convenient dosing schedule to facilitate both adherence to the regimen and completion of 4 weeks of PEP.

|

|

WHO (adults and adolescents)31 |

CDC (Health Care Personnel)32 |

|

Preferred PEP Regimen |

TDF + 3TC (or FTC) and LPV/r or ATV/r |

TDF/FTC + RAL |

|

Alternative PEP Regimen |

TDF + 3TC (or FTC) along with anyone of RAL, DRV/r or EFV |

TDF + 3TC (or FTC) or AZT + 3TC (or FTC) along with anyone of RAL, DRV/r, ETR, RPV, ATV/r, LPV/r |

Other options which can be given as PEP Only with Expert Consultation are abacavir (ABC), Efavirenz (EFV), Enfuvirtide (T20), Fosamprenavir (FOSAPV), Maraviroc (MVC), Saquinavir (SQV) and Stavudine (d4T).32

Certain ARVs are generally Not Recommended for use as PEP like didanosine (ddI), nelfinavir (NFV), tipranavir (TPV) while nevirapine (NVP) is contraindicated as PEP.32

PEP ARV regimens – children (≤10 years old):31

- In children, AZT + 3TC is the preferred backbone regimen.

- ABC + 3TC or TDF + 3TC (or FTC) can be considered as alternative regimens.

- LPV/r is recommended as the preferred third drug.

- An alternative third agent (age-appropriate) can be identified among ATV/r, RAL, DRV, EFV and NVP.

Situations for Which Expert Consultation for HIV PEP is Recommended32

|

Delayed (i.e., later than 72 hours) exposure report

Unknown source (eg. needle in sharps disposal container or laundry)

Known or suspected pregnancy in the exposed person

Breast-feeding in the exposed person

Known or suspected resistance of the source virus to antiretroviral agents

Toxicity of the initial PEP regimen

Serious medical illness in the exposed person

|

A close follow-up for exposed personnel should be provided that includes counseling, baseline and follow-up HIV testing, and monitoring for drug toxicity; follow-up appointments should begin within 72 hours of an HIV exposure.

Female condoms have been marketed as an alternative barrier method, but this device, like the male condom, also requires acceptance by the male partner. In this context, prevention options that can be used and controlled by women to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV would be useful.33

Multipurpose prevention technologies (MPTs) aim to combine HIV prevention with prevention of unintended pregnancy and/or prevention/treatment of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and reproductive tract infection. 34

MPTs are multi-indication products, comprising either (1) multiple active agents, each individually effective for a different indication; (2) a single active agent effective for multiple indications (e.g. a single active drug with both microbicidal and contraceptive properties); or (3) one or more active agents incorporated into a medical device (e.g. a microbicide-releasing condom or diaphragm).34

Microbicides

Microbicides are chemical products that are self-administered prophylactic agents that can be applied topically in the vagina or rectum as a single agent or multi-component strategy.33 Candidate microbicides have been developed for delivery through various means, including gels, creams, tablets, films, slow-release, vaginal rings etc.2

Microbicide products are being developed for use vaginally or rectally to prevent sexual transmission of HIV-1. Vaginal microbicides offer a potentially important new prevention option for women.2

1% Tenofovir Gel

- The CAPRISA 004 trial assessed the effectiveness and safety of a 1% vaginal gel formulation of tenofovir for the prevention of HIV acquisition in women in 889 South African women. The study showed that tenofovir gel reduced HIV acquisition by an estimated 39% overall, and by 54% in women with high gel adherence. Women in the trial were counselled to use the gel within 12 hours before and after sex, a regimen known as BAT-24.35

- The VOICE trial in 5,029 African women in South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe was designed to test daily use of both oral (pill form) or topical (gel form) tenofovir-based prevention. It found that none of the interventions tested—daily oral TDF, daily oral TDF/FTC and daily tenofovir gel—reduced the risk of HIV prevention. Analyses showed that the participants were not using the interventions regularly enough to have detectable drug levels in their blood. This suggests that they did not follow the daily regimen as prescribed.36

- FACTS 001 was a Phase III, randomized, controlled trial, involving multiple South African research centres, that was set up to assess the safety and effectiveness of the vaginal microbicide, tenofovir gel, in preventing HIV infection in sexually active HIV-negative women aged 18 to 30 years. The outcome of this study showed that pericoital vaginal tenofovir 1% gel was not effective in preventing HIV acquisition. There was an association between adherence based on returned applicators and HIV effectiveness, and a significant association between tenofovir levels in cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) and reduction in HIV incidence.37

- MTN 017 is the first-ever expanded safety study (Phase II trial) of a rectal microbicide candidate, a reformulated version of tenofovir gel. It began in late 2013. It will enroll 186 men who have sex with men at sites in Peru, South Africa, Thailand and the United States. In each 8 week study period participants were randomized to reduced glycerine (RG)-TDF rectal gel daily; or RG-TDF rectal gel before and after receptive anal intercourse (RAI) (or at least twice weekly in the event of no RAI); or took daily oral FTC/TDF. Participants were seen every 4 weeks. The study found that reduced glycerin tenofovir gel was safe. Participants were equally adherent to using gel before and after sex (93%) as they were to taking daily TDF/FTC 94% respectively. They were less adherent to using gel on daily basis 83%.38,54,55

Vaginal Rings: Dapivirine Ring

Vaginal rings are flexible, torus-shaped, silicone elastomer or thermoplastic devices that provide long-term, sustained or controlled delivery of pharmaceutical substances to the vagina for either local or systemic effect. They are generally positioned in the upper third of the vagina adjacent to the cervix, to be readily inserted and removed by the woman herself.2

The dapivirine ring is being tested for its ability to reduce the risk of HIV infection. It slowly releases the antiretroviral dapivirine. A new ring has to be inserted every four weeks to maintain drug delivery. Two current trials are evaluating whether the ring is safe and effective at reducing the risk of HIV infection.2,38

- ASPIRE (MTN 020) was launched by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) in 2012 and enrolled 2,629 HIV-infected women aged 18–45 years in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe. The ring was to be used for a period of 4 weeks and then replaced by another. The ring was impregnated with 25 milligrams (mg) of dapivirine. Dapivirine ring reduced the risk of acquiring HIV by 27% among women enrolled in the study.51

- The Ring Study (IPM 027) is sponsored by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM) and is enrolling 1,950 women aged 18–45 years at sites in Uganda and South Africa. The dapivirine ring reduced the risk of HIV infection by 31%.52

Although ART has a significant HIV prevention effect, it should be used in combination with other biomedical interventions that reduce HIV risk practices and/or reduce the probability of HIV transmission per contact event, including male and female condoms, needle and syringe programmes, opioid substitution therapy with methadone or buprenorphine and voluntary medical male circumcision.39

Medical Male Circumcision

Male circumcision is one of the oldest and most common surgical procedure performed on newborns and young boys for nonmedical reasons and was first proposed as an HIV-prevention intervention for men over a decade ago, based on observational data.40

Male circumcision is surgical removal of the foreskin – the retractable fold of tissue that covers the head of the penis. The inner aspect of the foreskin is highly susceptible to HIV infections. Trained health professionals can safely remove the foreskin of infants, adolescents and adults (medical male circumcision).41

Circumcision is known to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition among men. There could be many reasons as to how this could occur. The foreskin has a tendency to develop epithelial disruptions, or tears, during intercourse, which may allow HIV a portal of entry, and compared with the tissue of the outer foreskin, the foreskin’s HIV target cells (Langerhans cells with CD4 receptors) are closer to the epithelial surface. 41

The programmatic implementation of adult Medical Male Circumcision (MMC) in several Sub-Saharan African countries could, in 10 years, reduce HIV acquisition in men by at least 60%.42 It was observations from these three trials, i.e. Kisumu (Kenya), Rakai District (Uganda) and South Africa Orange Farm Intervention Trial, which demonstrated at least a 60% reduction in HIV infection among men who were circumcised.43

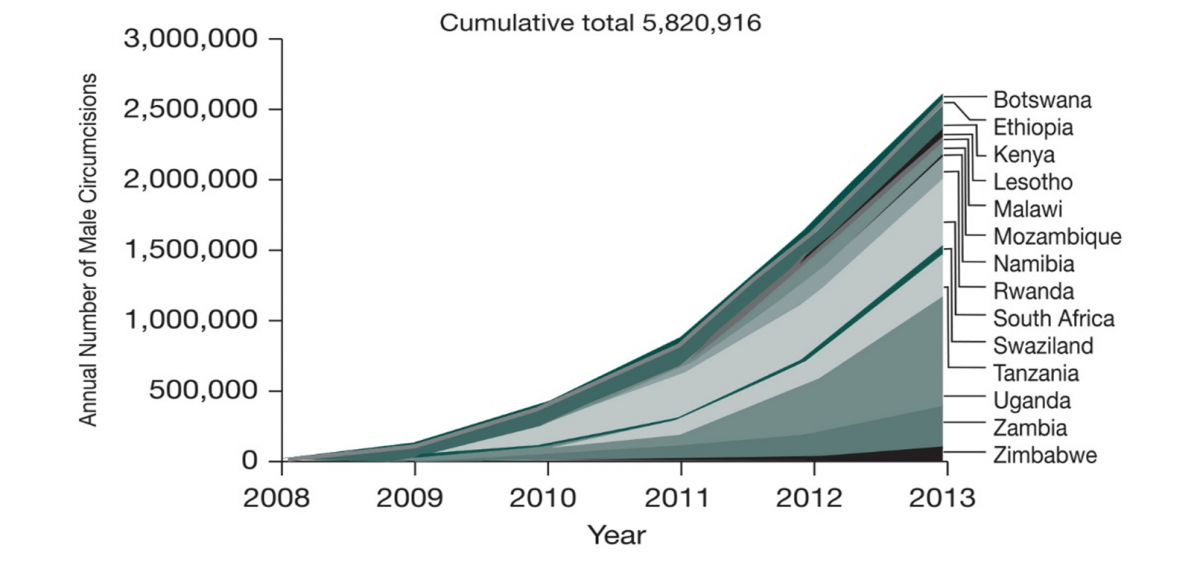

With successful efforts of scaling up the implementation of male circumcisions, there has been an impressive increase in the number of male circumcisions performed in 2013, with 2.7 million men in 14 priority countries of East and Southern Africa stepping forward for medical male circumcision and therefore leading to a cumulative total of 5.82 million males circumcised since 2008. 44

The WHO has laid down certain guidelines recommending the use of voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) and its implementation in targeted key population groups. Following are the WHO 2014 recommendations for the use of VMMC:39

- All key population groups39

– VMMC is recommended as an additional, important strategy for the prevention of heterosexually acquired HIV infection in men, particularly in settings with hyperendemic and generalized HIV epidemics and low prevalence of male circumcision.

– VMMC service provision should serve as an opportunity to address the sexual health needs of men; such services should actively counsel and promote safer sexual behaviour.

- Men who have sex with men39

– Due to lack of evidence of VMMC during receptive anal intercourse, it is not recommended to prevent HIV transmission in sex between men.

– Men who have sex with men (MSM) may still benefit from VMMC if they also engage in vaginal sex.

– In eastern and southern Africa where VMMC is offered for HIV prevention, MSM should not be excluded from VMMC services.

- People in prisons and other closed settings39

– VMMC is not one of the recommended interventions in the prison package.

- Sex workers (and clients of sex workers) 39

– Health messages and counselling should emphasize that resuming sexual relations before complete wound healing may increase the risk of HIV acquisition among recently circumcised HIV-negative men and may increase the risk of HIV transmission to female partners of recently circumcised HIV-positive men.

– “Men’s health services” offering VMMC to clients of sex workers or other men at higher risk (such as in serodiscordant couples) may be a promising approach in the high-priority countries of eastern and southern Africa to reach men at greater risk of HIV infection. This approach has not been systematically reviewed and evaluated.

- Transgender people39

– VMMC is not recommended for HIV prevention among transgender women.

- Adolescents from key populations39

– Countries with hyperendemic and generalized HIV epidemics and low prevalence of male circumcision should increase access to male circumcision services as a priority for adolescents and young men.

|

Type |

Summary characteristics |

Example |

|

Surgical-assist male circumcision devices |

Reusable metal or single-use disposable plastic devices employed during surgery and not worn by the client after the procedure. |

Unicirc SimpleCirc |

|

Clamp and latch male circumcision devices |

Disposable devices that use a clamping mechanism to hold the device in place and control bleeding at the site of incision and that are worn for about seven days after device placement and foreskin removal. |

Shang Ring Tara KLamp Ali’s Klamp Smartklamp |

|

Male circumcision devices with ligature compression |

Disposable devices that use a ligature to hold the device in place for about seven days and control bleeding at the incision after device placement and foreskin removal. |

Zhenxi Ring |

|

Male circumcision devices with elastic collar compression |

Disposable devices that use an elastic ring to induce necrosis of the intact foreskin. The device and necrotic foreskin are removed at the same time, about seven days after placement. |

PrePex |

In a WHO meeting held in Entebbe, Uganda, (November 2013), an analysis conducted comparing surgical methods to male circumcision devices was discussed. The outcomes of the analysis was based on a total of 1983 ShangRing and 2,417 PrePex procedure.45

It was observed that men reported a high level of satisfaction with the cosmetic result following both types of circumcision – device and conventional surgery. However, larger proportion of physicians and non-physicians expressed a preference for a device over conventional surgical circumcision.45

Common advantages reported by providers with the device techniques compared to the conventional procedure were as below:45

- easy to perform and faster

- better cosmetic results

- fewer complications

- remove the need for suturing

- cause less bleeding, and

- remove the need for routine injectable anaesthesia (in the case of the PrePex)

Therefore, VMMC is an important preventive strategy. However, it provides only partial protection and, therefore, should be only one element of a comprehensive HIV prevention package, which includes the following: the provision of HIV testing and counselling services; treatment for sexually transmitted infections; the promotion of safer sex practices; the provision of male and female condoms and promotion of their correct and consistent use.46

Condoms and Lubricants

Antiretroviral-based treatment and prevention options appear promising in controlling the disease progression and transmission. However, barrier methods still remains an important part of the comprehensive prevention package.

Condoms are an essential component of comprehensive efforts to control the HIV epidemic, both for those who know their status and for those who do not.47 Consistent and correct use of male condoms reduces sexual transmission of HIV and other STIs in both vaginal and anal sex by up to 94%.39 Male condoms are highly effective in preventing HIV transmission and female condoms have similar efficacy as the male condoms, but are 20 times more expensive.39

Use of water- or silicone-based lubricants (as opposed to petroleum-based) helps to prevent condoms from breaking and slipping. While fewer data are available on female condoms, evidence suggests that the use of female condoms also prevents HIV and STIs.39

WHO 2014 Recommendations39

In all key population groups the correct and consistent use of condoms with condom-compatible lubricants is recommended for all key populations to prevent sexual transmission of HIV and STIs.

WHO emphasizes on the need to enforce and promote the use of condoms. Male and female condoms should be made easily available and accessible. Condom promotion campaigns should increase awareness, promote the acceptability and benefits of condom use, and help to overcome social and personal obstacles to their use.

The recent epidemiological update by the UNAIDS shows that efforts taken worldwide have successfully contributed towards curbing the epidemic of HIV/AIDS. Up to 17 million HIV-infected individuals are receiving antiretroviral treatment as of 2015.1 The decline in the incidence of HIV is accelerating and prevention strategies will only enhance this success. Unless the number of new infections falls sharply, long-term costs associated with the provision of lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) could soon become prohibitive, potentially threatening advances achieved to date by the global AIDS response.2

Along with use of ARVs as prevention, other HIV prevention technologies are also being developed and likely to emerge in the foreseeable future. Continuous research and efforts are underway to develop these HIV prevention tools. The use of ART will need to be part of a combination prevention strategy to achieve successful outcomes. Therefore, with the newer technologies available for HIV prevention and those that will become available from ongoing research, the spread of HIV can be expected to be controlled.48

1. Global AIDS Update. UNAIDS 2016.

2. HIV Preventives Technology and Market Landscape; 2nd Edition;2014

3. PLoS One. 2013 Dec 30;8(12):e83193.

4. http://www.thebody.com/content/75211/how-can-i-prevent-hiv-transmission-infographic.html (last accessed 28th October 2015)

5. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012 November; 7(6): 600–606.

6. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States – 2014 Clinical Practice Guideline; CDC 2014.

7. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2587-99.

8. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2; 367(5):399-410.

9. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2; 367(5):423-34.

10. Lancet. 2013 Jun 15; 381(9883):2083-90.

11. CROI, 2015. Abstract 22LB

12. CROI, 2015. Abstract 23LB

13. IAS 2015; Abstracts MOAC0306LB, MOAC0305LB and MOSY0103

14. IAS 2015; Abstract TUAC0202.

15. Guideline on When To Start Antiretroviral Therapy And On Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis For HIV; WHO 2015

16. Technical update on Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP); WHO 2015

17. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010 Feb;31(2):74-81

18. IJBAR 2014; 05 (07). doi:10.7439/ijbar

19. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:493-505.

20. http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/hiv-study-named-2011-breakthrough-year-science (Last accessed on 28th October 2015)

21. IAS 2011; Oral Abstract MOAX0102

22. IAS 2015; Abstract MOAC0101LB

23. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents; DHHS 2015

24. BHIVA guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1 positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2015; BHIVA 2015

25. European AIDS clinical society guidelines, Version 8.0; EACS 2015

26. JAMA. 2014;312(4):410-425.

27. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach; WHO 2016 2nd Edition.

28. http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/mtct/en/ (Last accessed on 28th October 2015)

29. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015 Apr 15; 68(5):e77-83.

30. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2014 Oct 24; 6 :147-58.

31. Guidelines On Post-Exposure Prophylaxis For HIV And The Use Of Co-Trimoxazole Prophylaxis For HIV-Related Infections Among Adults, Adolescents And Children: Recommendations For A Public Health Approach; WHO 2014

32. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013; 34(9):875-92.

33. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 August; 26(4): 427–439.

34. BJOG. 2014 Oct; 121 Suppl 5:62-9.

35. Science. 2010 September 3; 329(5996): 1168–1174.

36. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:509-18

37. CROI, 2015. Abstract 26LB

38. Prevention on the line; AVAC report 2014-15

39. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations; WHO 2014

40. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63:S140–S143

41. Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention; WHO factsheet 2012

42. AIDS 2013, 27:2899–2907

43. New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications; UNAIDS 2007

44. WHO Progress Brief - Voluntary medical male circumcision for HIV prevention in priority countries of East and Southern Africa; WHO 2014

45. Use of Devices for Adult Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention in East and Southern Africa. Meeting report. 13–14 November 2013, Entebbe, Uganda

46. www.who.int/hiv/topics/malecircumcision/en/ (last accessed 28th October 2015)

47. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV Transmission (Review); the Cochrane Library (4) 2007.

48. AIDS. 2012 Aug 24;26(13):1585-98

49. http://www.prepwatch.org/advocacy/country-updates/ Last accessed 17th May 2016

50. Impact of an Innovative Approach to Prevent Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV – Malawi, July 2011 – September 2012, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), March 1, 2013; 62(08);148-151

51. CROI, 2016. Abstract 109LB

52. CROI, 2016. Abstract 110LB

53. Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations WHO 2014

54. http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/news/studies/mtn017/qa Last accessed May 2016

55. CROI, 2016. Abstract 108LB