Depression and Diabetes: A Debilitating Comorbid Condition

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is one of the serious medical diseases with an estimated prevalence of 3 to 4% in the general population worldwide.1 Reports have suggested a 69% increase in numbers of diabetic patients by 2030 in developing countries. Depression is another predominant condition worldwide with estimates of around 340 million people suffering from depression at any given time.2 The combination of depression and diabetes considerably worsens the health related outcomes as shown by a worldwide health survey from around 60 countries.3 In patients with diabetes, the prevalence of depression is reported to be significantly higher, 17.6%, than in those without diabetes, 9.8%,4 which may have a negative impact on the management and recovery from comorbid medical disorder.5 Moreover, comorbid depression and diabetes may significantly increase the all-cause mortality than either of the disorders alone.4 Also, studies have shown that diabetic patients with major depression have poor adherence to antidiabetic regimens, poor glycemic control, increases the severity of diabetic symptoms, and the risk of retinopathy and macrovascular complications.5,6 Depression is often unrecognized and untreated in patients with both conditions, depression as well as diabetes. Studies have suggested a less than optimal recognition and treatment of depression, and only around 25% of depressed diabetic patients receive care.5

Bidirectional Relationship of Depression and Poor Glycemic Control

Depression and glycemic control is likely to have a bidirectional relationship.7 Depression may lead to a greater release of counter-regulatory hormones and lead to impaired disposition of carbohydrates thereby increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes. Conversely, increased arousal of the nervous system by hyperglycemia may increase the susceptibility of the patient to environmental stress thereby increasing the frequency of depression.6

Impact of Depression in Developing Diabetes

The impact of depression on the stress pathways in diabetic patients affects glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels.7 The effect of stress on the neuroendocrine system activates the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and causes various endocrine abnormalities, such as high cortisol and low sex steroid levels. These stress-related changes may affect health behaviors such as medication adherence, drinking and smoking as well as antagonize the actions of insulin. Furthermore, increased visceral adiposity also contributes to insulin resistance and plays an important role in diabetes.1

Emotional Burden of Diabetes

Diabetes in itself increases the emotional burden in patients and causes distress in them. Moreover, failure to intensify insulin therapy in time may also lead to psychological insulin resistance (fear of insulin, side effects of hypoglycemia, weight gain, complexity of insulin treatment and need to self-monitor blood glucose to adapt doses), which may further cause delay in starting the insulin therapy in patients with already poor glycemic control. 7

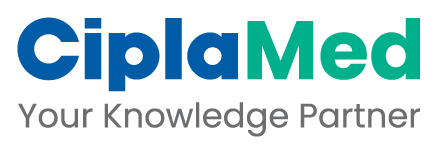

Moreover, few antidepressants, patient’s diet, corresponding weight changes, and physical inactivity associated with chronic depression may cause hyperglycemia leading to diabetes. Figure 1 demonstrates a relationship between diabetes and depression and effect of antidepressant therapy on this comorbidity. 6

Management of Concomitant Depression in Diabetic Patients

A chronic and severe course of depression is reported to occur in depressed individuals with diabetes compared with those without diabetes. An episode of depression typically lasting for 6 to 9 months may last for up to 2 years. Most patients experience recovery, but unfortunately the risk of relapse is high in patients recovered from initial episode of major depression. Therefore, specific intervention is usually required for providing effective relief from depression. Long-term antidepressant pharmacotherapy is the preferred approach for treating frequently recurring episodes of depression. 6

SSRIs: A Preferred Choice for Treating Comorbid Depression and Diabetes

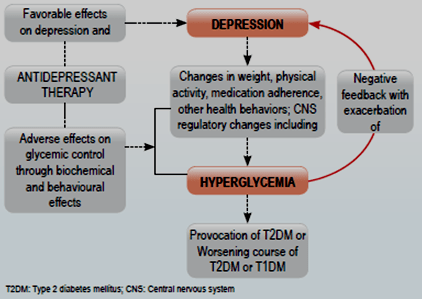

Antidepressants having the potential for adverse effects and drug interactions are suggested to be avoided in the management of depression in patients with diabetes.6 Evidence has shown that tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), although effective in treating depression, destabilize the glycemic control in some diabetic patients.5 An 8 week study conducted in diabetic patients with TCA nortriptyline demonstrated a significantly worse glycemic control in patients with depression than in those without as was observed after 5 years of follow-up period (Figure 2). Hence, TCAs and MAOIs are rarely used to treat depression in diabetic patients.6

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) lead to improvement of both, the dietary compliance and HbA1c levels, in patients with diabetes. Short term use with SSRIs does not cause hyperglycemia; moreover, its positive effect on weight loss improves the metabolic control, thereby improving insulin resistance. Thus, SSRIs appear to be preferred antidepressant in patients with concomitant diabetes. . 1, 6

Escitalopram is Effective in Treating Depression and Achieving Glycemic Control in Patients with Comorbid Depression and Diabetes

Escitalopram has high selectivity for the serotonin transporter and minimal inhibitory effect on the cytochrome P-450 2D6 and 3A4 isoenzymes that are responsible for the metabolism of many drugs used in the treatment of diabetes. Escitalopram is also reported to significantly reduce depression without risk of weight gain or hyper or hypoglycaemia.5

Researchers in a study evaluated the effect of escitalopram in patients with diabetes mellitus with comorbid depression and the relationship of treatment response for depression and glycemic control. Escitalopram was administered in 40 patients for up to 12 weeks. Escitalopram was started at 10 mg/day for 3 weeks, after which the dose was increased to 15 mg/day for 6 weeks in patients with ?50% reduction in baseline Hamilton Depression rating scale (HAM-D) score and further increased to 20 mg/day in those still with ?50% reduction in baseline HAM-D score.5

- Primary outcome measures included HAM-D assessment at 3, 6, and 12 weeks.

- Secondary outcomes measures included fasting and post-prandial plasma glucose level and HbA1C.

- Other outcomes included weight and waist circumference, lipid profile, renal function test and fundus examination.

Findings Revealed:

- A statistically significant mean decrease in HAM-D scores was observed at 3, 6 and 12 weeks of follow up respectively (p<0.001; Table 1).

- Compared with the baseline, a statistically significant (p<0.001) decrease was observed in fasting (mean decrease at 12 weeks was 68.72±40.53 mg/dl) and post-prandial plasma glucose level (mean decrease at 12 weeks was 109.95±55.32 mg/dl) after escitalopram treatment (Table 1).

- A statistically significant decrease in mean HbA1C was observed at 12 weeks (mean decrease at 12 weeks was 1.36 ± 0.63) (p<0.001; Table 1) after treatment.

- No significant decline of weight at 6 and 12 weeks after treatment (p>0.05). No statistical significant change was observed in mean cholesterol, triglyceride, LDL, HDL and VLDL levels at 12 weeks after treatment. There was non-significant change in renal parameters at 12 weeks (p>0.05)

|

|

At baseline mean ± SD |

At 3 weeks mean±SD |

At 6 weeks mean ±SD |

At 12 weeks mean ± SD |

p value |

|

FPG (mg/dl) |

177.66 ± 57.81 |

- |

134.55 ± 39.79 |

108.95 ± 25.84 |

<0.001*** |

|

PPPG (mg/dl) |

254.63 ± 71.23 |

- |

177.35 ± 50.65 |

146.27 ± 25.69 |

<0.001*** |

|

HbA1c (%) |

9.88 ± 1.73 |

- |

- |

8.53±1.34 |

<0.001*** |

|

HAM-D scores |

22.33 ± 5.22 |

12.53 ± 4.70 |

8.18 ± 4.34 |

4.75 ± 2.24 |

<0.001*** |

|

***very highly significant (<0.001); FPG: Fasting plasma glucose; PPPG: post-prandial plasma glucose; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression rating scale | |||||

Therefore, escitalopram has beneficial effects on glycemic control and is effective in patients with comorbid depression and diabetes.5

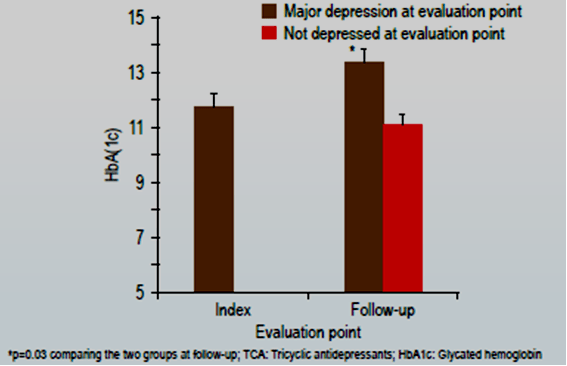

Another study by Dhavale et al showed high prevalence of stressors (84%) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Amongst the patients started on Escitalopram therapy, the mean glucose levels had reduced in 47% of patients compared with baseline values. A statistically significant decrease was observed in the mean fasting blood sugar (p=0.029) and post lunch blood sugar levels (p=0.004) during the follow-up compared with the baseline values (Figure 3).1

Summary

- Concomitant depression and diabetes is observed to be the most disabling comorbidity. The prevalence of depression is significantly higher in diabetic patients compared with those without diabetes. Also, diabetic patients with depression have poor adherence to medications, poor glycemic control, and increased risk of diabetic-related complications.

- Depression worsens glycemic control by having an impact on the stress pathway in diabetic patients. Conversely, increased arousal of the nervous system by hyperglycemia and management of diabetes increases the emotional burden and causes distress in these patients.

- SSRIs are preferred over other classes of antidepressant agents since it has shown to have a positive effect on weight loss and improve the metabolic control, unlike TCAs and MAOIs which destabilize the glycemic control.

- Escitalopram significantly decreases the HAM-D scores, the fasting and post-prandial plasma glucose levels and glycosylated hemoglobin levels in patients with comorbid depression and diabetes. Therefore, escitalopram is a favorable choice of treatment for comorbid depression and diabetes.

References

- Dhavale HS et al. Depression and diabetes: impact of antidepressant medications on glycaemic control. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013; 61(12):896-9.

- Sweileh WM et al. Prevalence of depression among people with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a cross sectional study in Palestine. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14:163.

- Moussavi S et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007; 370(9590):851-8.

- Singh BK et al. Effect of antidepressants, on metabolic control, in patients of Diabetes mellitus with comorbid depression. Delhi Psychiatry Journal. 2013; 16(2): 317-21

- Gehlawat P et al. Diabetes with comorbid depression: role of SSRI in better glycemic control. Asian J Psychiatr. 2013; 6(5):364-8.

- Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Depression in diabetic patients: the relationship between mood and glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications. 2005; 19(2):113-22.

- Ascher-Svanum H et al. Associations between Glycemic Control, Depressed Mood, Clinical Depression, and Diabetes Distress Before and After Insulin Initiation: An Exploratory, Post Hoc Analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2015; 6(3):303-16.