Opportunistic Infections

Fact Sheets

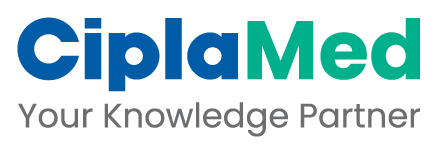

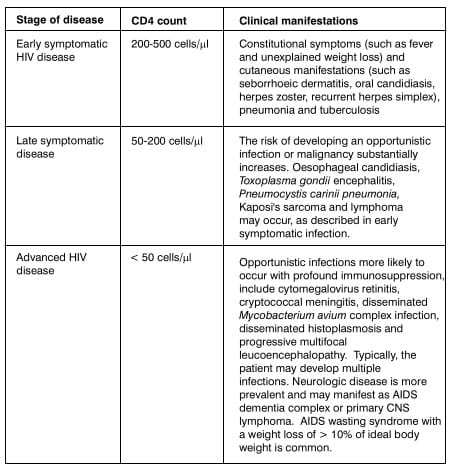

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) causes a chronic infection that leads to profound immunosuppression. A

hallmark of this process is the depletion of CD4 lymphocytes, and this predisposes the patient to develop a

variety of opportunistic infections and certain neoplasms.

The course of the infection may vary, with some individuals developing immunodeficiency within 2 to 3 years and

others remaining asymptomatic for 10 to 15 years. A typical course spanning over about 10 years is depicted in

the following chart:

Thus, the CD4 T-lymphocyte count is the best-validated predictor of the likelihood of developing an opportunistic

infection. Susceptibility to opportunistic infections increases as HIV-induced immunodeficiency becomes more

severe.

Management of HIV infection involves treating the opportunistic infections, as well as inhibiting viral

replication using antiretrovirals. It is important to note that drug interactions may occur between the various

drugs in the antiretroviral regimen, as well as between antiretrovirals and drugs used to treat the

opportunistic infections. A pertinent example is the interaction between rifampicin and antiretrovirals

(discussed under "Tuberculosis"). An excellent online tool to ascertain possible drug interactions is

available at www. hiv-druginteractions. org.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

May be pulmonary or extra-pulmonary, such as lymphadenitis, meningitis etc. Cough, weight loss, night sweats,

fever, swollen lymph nodes, or organ-specific symptoms. However, extrapulmonary disease is more common in

HIV-1-infected persons than in non-HIV-1-infected persons.

- Chest radiography.

- Ultrasonography or CT scan for extra-pulmonary TB.

- Sputum samples for AFB smear and culture obtained from patients with pulmonary symptoms, cervical adenopathy

or chest radiographic abnormalities.

- Among patients with signs of extrapulmonary TB, needle aspiration of skin lesions, nodes, pleural or

pericardial fluid might allow for rapid diagnosis, culture, and susceptibility testing.

- Tissue biopsy is helpful among patients with negative fine-needle aspirates.

- Among patients with signs of disseminated disease, mycobacterial blood culture is diagnostic.

Tuberculous Pleural Effusion

Obliteration of right costophrenic angle in a patient with early HIV disease

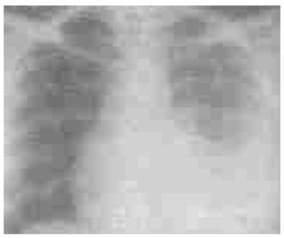

A number of potential problems can be encountered if antiretroviral therapy (ART) and anti-TB therapy (AKT) are

prescribed concurrently. These include overlapping toxicities, increased pill burden and risk of sub-optimal

adherence, drug-drug interactions and inflammatory reactions.

For patients with active TB in whom HIV infection is diagnosed and ART is required, the first priority is to

initiate standard anti-TB treatment. The optimal time to initiate ART is not known. Case-fatality rates in

patients with TB during the first two months of TB treatment are high, particularly in settings with a high

prevalence of HIV, suggesting that ART should begin early. On the other hand, considerations of pill burden,

drug-drug interactions, toxicity, and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) support the later

initiation of ART

Thus, a balance needs to be established between the risk of disease progession and death it ART is deferred,

against an increased risk of inflammatory reactions and other adverse events if ART is started rapidly after TB

diagnosis.

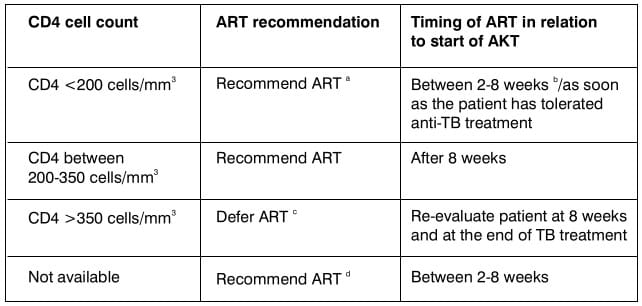

The WHO (2006) recommendations are as follows:

In patients with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3: ART should be started as soon as the patient

has tolerated and stabilized on TB treatment. It usually takes between 2 and 8 weeks after the start of TB

treatment.

In patients with CD4 counts >200 ceils/mm3: Initiation of ART may be delayed until after

the initial intensive phase of TB treatment has been completed.

In patients with CD4 counts >350 cells/mm3: ART can be delayed until after the

completion of short-course TB therapy, following a reassessment of the patient's eligibility for ART and

evaluation of the response to TB therapy and of CD4 counts, if available.

A fungal infection.

The occurrence of pharyngeal or esophageal candidiasis is recognized as an indicator of immune suppression, and

these are most often observed in patients with CD4 counts < 200 cells/μL. In contrast, vulvovaginal

candidiasis is common among healthy, adult women and is unrelated to HIV-1 status.

Candida albicans is the predominant causative agent of all forms of mucocutaneous candidiasis. Less

frequently, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, C. kruseii and several other species may cause

candidiasis.

Oropharyngeal Candidiasis

Oropharyngeal candidiasis is characterized by painless, creamy white, plaque-like lesions of the buccal or

oropharyngeal mucosa or tongue surface. Lesions can be easily scraped off with a tongue depressor or other

instrument. Less commonly, erythematous patches without white plaques can be seen on the anterior or posterior

upper palate or diffusely on the tongue. Angular chelosis is also noted on occasion.

Oral Candidiasis (thrush) in intermediate HIV disease

Numerous superficial white pustules that 'peel off' as a white membrane leaving behind erosions.

Esophageal Candidiasis

Esophageal candidiasis is occasionally asymptomatic but often presents with fever, retrosternal burning pain or

discomfort, and odynophagia.

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Vulvovaginitis is characterized by a creamy to yellow-white adherent vaginal discharge associated with mucosal

burning and itching.

Oropharyngeal Candidiasis

Visual examination, ability to scrape off the superficial whitish plaques.

Esophageal Candidiasis

Usually diagnosed presumptively if dysphagia and odynophagia are present with thrush. Alternatively, upper Gl

tract endoscopy followed by histopathologic demonstration and culture confirmation.

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Vulvovaginal candidiasis is based on clinical presentation coupled with the demonstration of characteristic

yeast forms in vaginal secretions examined microscopically after KOH preparation.

Oropharyngeal Candidiasis

Although initial episodes of oropharyngeal candidiasis can be adequately treated with topical therapy, including

clotrimazole troches or nystatin suspension, oral fluconazole (200 mg on the first day, followed by 100 mg once

daily for 2 weeks) is as effective, superior to topical therapy, more convenient and generally better tolerated.

Itraconazole oral solution for 7-14 days is as effective as oral fluconazole but less well tolerated.

Ketoconazole and itraconazole capsules are less effective than fluconazole because of their more variable

absorption and should be considered second line alternatives.

Esophageal Candidiasis

Systemic therapy is required for effective treatment of esophageal candidiasis. A 14-21 day course of either

fluconazole (200 mg on the first day, followed by 100 mg once daily for 3 weeks) or itraconazole solution is

highly effective. As with oropharyngeal candidiasis, ketoconazole and itraconazole capsules are less effective

than fluconazole because of variable absorption.

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Responds readily to short-course oral or topical treatment with any of several therapies including single-dose

regimens:

- Topical azoles (clotrimazole, butaconazole, miconazole, ticonazole, or terconazole)

- Topical nystatin

- Itraconazole oral solution

- Oral fluconazole (150 mg as a single dose)

Fluconazole Refractory Oropharyngeal Candidiasis

Responds at least transiently to itraconazole solution or amphotericin B oral suspension or intravenous

amphotericin B.

Fluconazole Refractory Esophageal Candidiasis

Responds to caspofungin or intravenous amphotericin B.

Majority of HIV specialists do not recommend secondary prophylaxis (chronic maintenance therapy).

Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV).

VZV causes 2 clinically distinct diseases. Varicella (or chickenpox) is a common and extremely contagious acute

illness that occurs in epidemics among school-aged children and is characterized by a generalized vesicular

rash. VZV establishes latency following primary infection. Reactivation of latent VZV results in herpes zoster

(or shingles), a localized cutaneous eruption that is most common among the elderly.

Complications of both varicella and herpes zoster are more frequent in immunocompromised patients. The incidence

of herpes zoster is greater in HIV-infected patients than that in the general population and can occur at any

CD4 count.

Herpes zoster (Shingles)

Herpes zoster might follow a prodrome of pain that resembles a burn or muscle injury in the affected dermatome:

skin lesions, which are similar to chickenpox in appearance and evolution, develop in the same dermatome. In a

patient with a damaged immune system as in HIV/AIDS, it may involve multiple dermatomes.

Ocular zoster

Acute retinal necrosis occurs as a peripheral necrotizing retinitis with yellowish thumbprint lesions, retinal

vascular sheathing, and vitritis with a high rate of visual loss, often caused by retinal detachment.

Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus

Haemorrhagic vesicles and erosions on a background of erythema and edema in early stage HIV disease. Note

extension to maxillary branch.

Varicella (Chickenpox)

Chickenpox, the principal clinical manifestation of primary VZV in childhood or adulthood is uncommon in adults

and adolescents with HIV-1 infection. When chickenpox occurs, it begins with a respiratory prodrome, followed by

the appearance of pruritic vesiculopapular lesions that are more numerous on the face and trunk than on the

extremities. Lesions evolve over a 5-day period through macular, papular, vesicular pustular and crust stages.

In profoundly immunocompromised hosts, vesicles can persist for weeks and coalesce to form large lesions that

resemble a burn.

Other

VZV has been associated with transverse myelitis, encephalitis, and vasculitic stroke among HIV-uninfected

persons.

Herpes zoster

The characteristic vesicular rash usually makes it an obvious clinical diagnosis. If the presentation is

atypical, the diagnosis can be best confirmed by testing a smear of a swab of the base of a skin lesion for the

presence of VZV antigen by a direct fluorescent antibody method.

Ocular zoster

VZV retinitis is a clinical diagnosis made by the typical clinical appearance of the retina and confirmed by a

history of concurrent or recent cutaneous zoster.

Varicella

Distinctive appearance - a clinical d iagnosis is usually accurate.

Herpes zoster

The recommended treatment for localized dermatomal herpes zoster is acyclovir, famciclovir or valacyclovir for

7-10 days. If cutaneous lesions are extensive or if clinical evidence of visceral involvement is observed,

intravenous acyclovir should be initiated and continued until cutaneous lesions and visceral disease are clearly

resolving.

Ocular zoster

Progressive outer retinal necrosis is rapidly progressive. Recommended treatment is high-dose intravenous

acyclovir in combination with foscarnet. Concomitant laser retinal photocoagulation might be needed to prevent

retinal detachments.

Varicella

Intravenous acyclovir for 7-10 days is the recommended initial treatment for adults and adolescents with

chickenpox. Switching to oral therapy after the patient has defervesced if no evidence of visceral involvement

exists might be permissible.

Successful treatment with intravenous acyclovir has been reported.

Among patients with suspected or proven acyclovir-resistant VZV infections, treatment with

intravenous foscarnet is the recommended alternative therapy.

No drug has been proven to prevent the recurrence of zoster (shingles) among HIV-1 infected persons.

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and Herpes simplex virus type 2(HSV-2)

HSV orolabialis

HSV orolabialis is the most common manifestation of HSV-1 infection presenting with a sensory prodrome in the

affected area, rapidly followed by the evolution of lesions from papule to vesicle, ulcer, and crust stages on

the lips. Ulcerative lesions are usually the only stage observed on mucosal surfaces. The course of illness in

untreated subjects is 7-10 days. Lesions recur 1 -12 times per year and are often triggered by sunlight or

stress.

HSV genitalis

HSV genitalis is the more common manifestation of HSV-2 infection. Perineal lesions on keratinylated skin are

similar in appearance and evolution to external orofacial lesions. Local symptoms include a sensory prodrome

consisting of pain and pruritis. Ulcerative lesions are usually the only stage observed on vaginal or urethral

mucosal surfaces.

Mucosal disease is generally accompanied by dysuria, vaginal or uretheral discharge; inguinal lymphadenopathy,

particularly in primary infection, is common with perineal disease.

Others

HSV keratitis, neonatal HSV, HSV encephalitis, and herpetic whitlow are similar in presentation and treatment to

those diseases observed in HIV-seronegative persons but might be more severe.

Diagnostic Procedures

HSV infections are usually diagnosed on the basis of characteristic skin, mucous membrane, or ophthalmic

lesions. Smear, viral culture, or HSV antigen detection can confirm the diagnosis.

Herpes Simplex

Typical grouped vesicular lesions of herpes simplex are seen at an unusual site in early stage HIV disease.

Scars of previous attack of herpes simplex are seen in the same region. Differential diagnosis includes

recurrent herpes zoster affecting the same dermatome.

HSV orolabialis

Orolabial lesions can be treated with oral famciclovir, valacyclovir, or acyclovir for 7 days.

Moderate-to-severe mucocutaneous HSV lesions are best treated initially with intravenous acyclovir. Patients may

be switched to oral therapy after the lesions have completely healed.

HSV genitalis

Initial or recurrent genital HSV should be treated with oral famciclovir, valacyclovir or acyclovir for 7-14

days.

HSV keratitis

Trifluridine is the treatment of choice for herpes keratitis, one drop onto the cornea every 2 hours, not to

exceed 9 drops/day; it is not recommended for longer than 21 days.

HSV encephalitis

Intravenous acyclovir, 10 mg/kg body weight every 8 hours for 14-21 days, is required for HSV encephalitis.

The treatment of choice for acyclovir-resistant HSV is IV foscarnet. Topical trifluridine or cidofovir also has

been used successfully for lesions on external surfaces, although prolonged application for 21 - 28 days or

longer might be required.

Persons who have frequent or severe recurrences can be administered daily suppressive therapy with oral

acyclovir, oral famciclovir, or oral valacyclovir. Intravenous foscarnet or cidofovir can be used to treat

infection caused by acyclovir-resistant isolates of HSV.

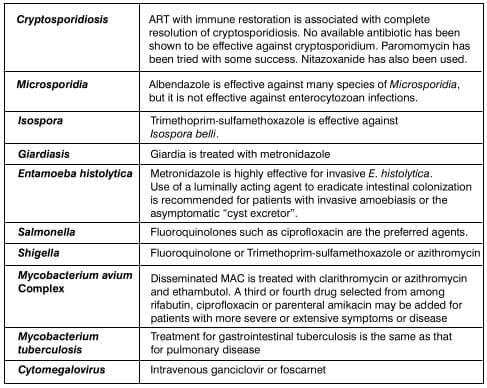

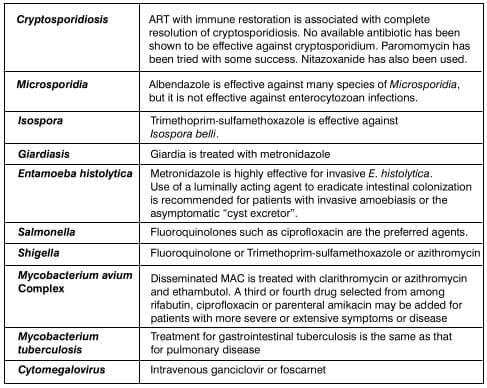

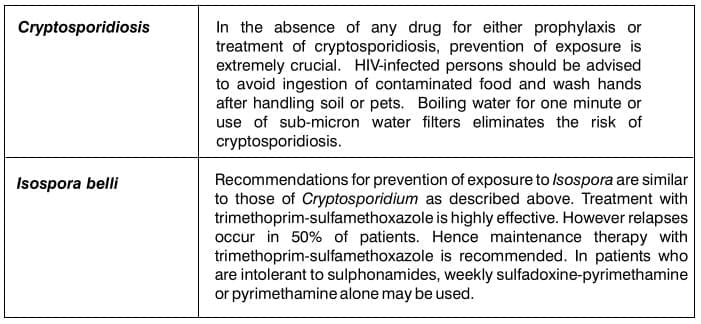

- Bacteria: Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter

- Parasitic infections: Cryptosporidium, Isospora, Giardia, Microsporidia, Entamoeba histolytica

- Mycobacterial infections: Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- Viral infections: Cytomegalovirus

- Drug-associated diarrhoea: Certain antiretrovirals such as protease inhibitors (e.g. nelfinavir)

commonly cause diarrhoea

- Idiopathic diarrhoea, often labelled 'HIV enteropathy'

Diarrhoea results from either small intestinal or colonic pathologic conditions. A careful history and physical

examination will direct the evaluation and treatment strategy of AIDS-associated diarrhoea.

Small-intestinal disease produces large volume diarrhoea that is frequently associated with dehydration and serum

electrolyte abnormalities. Abdominal pain, gaseous distension, nausea and vomiting also may be present. Tenesmus

and fecal leukocytes are absent.

Colonic diarrhoea is less voluminous, and dehydration is uncommon. Tenesmus and left lower quadrant pain are

common.

Bacterial infections

Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter cause more severe diarrhoea with longer duration of

illness in the immunocompromised host. The diagnosis is established through cultures of stool and blood.

Endoscopy may be useful.

Parasitic infections

Cryptosporidium, Isospora, Giardia and Microsporidia all infect the small intestine.

Entamoeba histolytica is uncommon but when present involves the caecum, ascending colon and terminal

ileum. Strongyloides stercoralis may also be encountered. The diagnosis can be established through

microscopic identification of oocytes in stool or tissue.

Viral Infections

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most important viral cause of AIDS-associated diarrhoea. CMV may affect any part of

the Gl tract; colitis and oesophagitis are quite common.

Mycobacterial infections

Mycobacterium avium is found in macrophages in the lamina propria of the small intestine or colon.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is most commonly found in the caecum and terminal ileum.

Pneumocystis jiroveci is a ubiquitous organism classified as a fungus but which shares biologic

characteristics with protozoa. The taxonomy of the organism has been changed: Pneumocystis carinii now

refers only to the pneumocystis that infects rodents, and Pneumocystis jiroveci refers to the distinct

species that infects humans. The abbreviation PCP is still used to designate Pneumocystis pneumonia.

Subacute onset of progressive exertional dyspnea, fever, nonproductive cough, and chest discomfort that worsens

over a period of days to weeks. Oral thrush is a common co-infection.

Pulmonary examination is usually normal at rest. With exertion, tachypnea, tachycardia, and diffuse dry rales

might be observed.

The chest radiograph typically demonstrates diffuse, bilateral, symmetrical interstitial infiltrates emanating

from the hila in a butterfly pattern.

Histopathologic demonstration of organisms in tissue, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or induced sputum.

Pneumocystis jiroveci Pneumonia (PCP) Diffuse small acinar shadows (arrows), with ground glass

appearance in both lower lobes suggests PCP

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) is the treatment of choice.

Alternative therapeutic regimens include:

- Dapsone and TMP for mild-to-moderate disease

- Primaquine plus clindamycin

- Intravenous pentamidine

- Atovaquone suspension

- Trimetrexate with leucovorin

For moderate to severe disease, the common practice is to use parenteral pentamidine, primaquine combined with

clindamycin, or trimetrexate (with or without oral dapsone) plus leucovorin. For mild disease, atovaquone is a

reasonable alternative.

Patients who have a history of PCP should be administered secondary prophylaxis (chronic maintenance therapy) for

life with TMP-SMX unless immune reconstitution occurs as a result of ART.

Alternatives are dapsone, dapsone combined with pyrimethamine, atovaquone or aerosolized pentamidine.

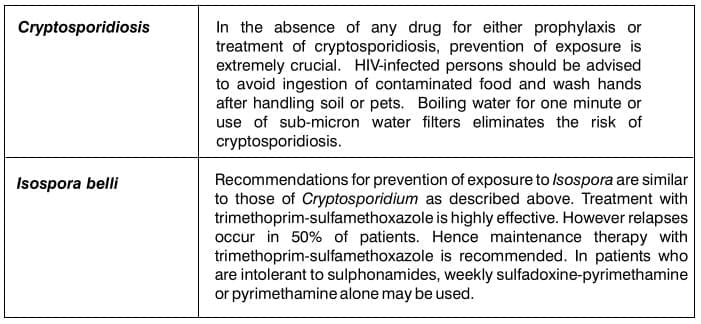

Virtually all HIV-1-associated cryptococcal infections are caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var

neoformans.

Cryptococcosis among patients with AIDS most commonly occurs as a subacute meningitis or meningoencephalitis with

fever, malaise and headache. Certain patients might present with encephalopathic symptoms (e.g., lethargy,

altered mentation, personality changes and memory loss).

Disseminated disease is a common manifestation, with or without concurrent meningitis. Approximately half of the

patients with disseminated disease have evidence of pulmonary rather than meningeal involvement. Symptoms and

signs of pulmonary infection include cough or dyspnea and abnormal chest radiographs. Skin lesions might be

observed.

Cryptococcal antigen is almost invariably detected in the CSF. If disseminated or other organ disease is

suspected in the absence of meningitis, a fungal blood culture is also diagnostically helpful. Detection of

cryptococcal antigen in serum might be useful in initial diagnosis.

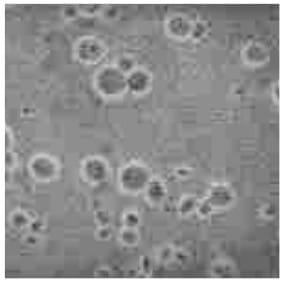

Cryptococcus Smear

India ink preparation brings out the prominent translucent capsule of the organism.

Untreated cryptococcal meningitis is fatal. The recommended initial treatment for acute disease is amphotericin

B, usually combined with flucytosine, for a 2-week duration followed by fluconazole alone for an additional 8

weeks.

Itraconazole is an acceptable though less effective alternative. The principal initial intervention for reducing

symptomatic elevated intracranial pressure is repeated daily lumbar punctures. CSF shunting should be considered

for patients in whom daily lumbar punctures are no longer being tolerated or whose signs and symptoms of

cerebral edema are not being relieved.

The optimal therapy for those with treatment failure is not known. Those who have failed on fluconazole should be

treated with amphotericin B with or without flucytosine as indicated previously, and therapy should be continued

until a clinical response occurs. Higher doses of fluconazole in combination with flucytosine also might be

useful.

Patients who have completed initial therapy for cryptococcosis should be administered lifelong suppressive

treatment (i.e., secondary prophylaxis or chronic maintenance therapy), unless immune reconstitution occurs as a

consequence of ART. Fluconazole is superior to itraconazole for preventing relapse of cryptococcal disease and

is the preferred drug.

The most common clinical presentation of T. gondii infection among patients with AIDS is focal encephalitis with

headache, confusion, or motor weakness and fever. Physical examination might demonstrate focal neurological

abnormalities, and in the absence of treatment, disease progression results in seizures, stupor and coma.

Retinochoroiditis, pneumonia, and evidence of other multifocal organ system involvement can be seen after

dissemination of infection but are rare manifestations in this patient population.

CT scan or MRI of the brain will typically show multiple contrast-enhancing lesions, often with associated edema.

Positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning might be

useful for distinguishing between Toxoplasmic encephalitis (TE) and primary central nervous system (CNS)

lymphoma, but no imaging technique is completely specific.

HIV-1 infected patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis are almost uniformly seropositive for anti-toxoplasma IgG

antibodies. Brain biopsy is reserved for patients failing to respond to specific therapy.

Toxoplasmosis

CT scan-post contrast. Multiple granulomas (arrows) surrounded by minimal vasogenic edema. However, presence of

multiple lesions with a target sign and positive toxoplasma titre suggested toxoplasmosis. Prompt response to a

trial of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine favoured toxoplasmosis.

Treatment

The initial therapy of choice consists of combination of pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine plus leucovorin. The

preferred alternative regimen for patients unable to tolerate or who fail to respond to first-line therapy is

pyrimethamine plus clindamycin plus leucovorin.

Management of Treatment Failure

A brain biopsy, if not previously performed, should be strongly considered for patients who fail to respond to

initial therapy.

Prevention of Recurrence

Patients who have successfully completed a 6-week course of initial therapy should be administered lifelong

secondary prophylaxis unless immune reconstitution occurs because of ART

Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellular

MAC disease among patients with AIDS, in the absence of ART, is generally a disseminated multiorgan infection.

Early symptoms might be minimal and might precede detectable intermittent or continuous mycobacteremia by

several weeks. Symptoms include fever, night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

Other localized manifestations of MAC disease have been reported most commonly among persons who are receiving

and who have responded to ART. Localized syndromes include cervical or mesenteric lymphadenitis, pneumonitis,

pericarditis, osteomyelitis, skin or soft tissue abscesses, genital ulcers or CNS infection.

Laboratory abnormalities particularly associated with disseminated MAC disease include anaemia (often out of

proportion to that expected for stage of HIV-1 disease) and elevated liver alkaline phosphatase. Hepatomegaly,

splenomegaly or lymphadenopathy (paratracheal, retroperitoneal, para-aortic, or less commonly peripheral) might

be identified on physical examination or by radiographic or other imaging studies.

A confirmed diagnosis of disseminated MAC disease is based on compatible clinical signs and symptoms coupled with

the isolation of MAC from cultures of blood, bone marrow, or other normally sterile tissue or body fluids.

Other ancillary studies provide supportive diagnostic information, including AFB smear and culture of stool or

biopsy material obtained from tissues or organs, radiographic imaging of the abdomen or mediastinum for

detection of lymphadenopathy, or other studies aimed at isolation of organisms from focal infection sites.

Initial treatment of MAC disease should consist of two antimycobacterial drugs to prevent or delay the emergence

of resistance. Clarithromycin is the preferred first agent. It appears to be associated with more rapid

clearance of MAC from the blood.

However, azithromycin can be substituted for clarithromycin when drug interactions or clarithromycin intolerance

preclude the use of clarithromycin.

Ethambutol is the recommended second drug. Some clinicians would add rifabutin as a third drug. The addition of

rifabutin should be considered in persons with advanced immunosuppression (CD4 T lymphocyte

count<50cells/μL), high mycobacterial loads (> 2 log10 colony units/mL of blood), or in the

absence of effective ART, settings in which mortality is increased and emergence of drug resistance is most

likely. If rifabutin cannot be used because of drug interactions or intolerance, a third or fourth drug may be

selected from among eitherthefluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin orlevofloxacin) or parenteral amikacin.

Patients who have had disseminated MAC disease diagnosed and who have not previously been treated with or are not

receiving potent ART should generally have ART initiated simultaneously or within 1-2 weeks of initiation of

antimycobacterial therapy for MAC disease. If ART has already been instituted, it should be continued and

optimized for patients.

Persons who have symptoms of moderate-to-severe intensity because of an immune recovery inflammatory syndrome in

the setting of ART should receive treatment initially with nonsteroidal, anti-inflammatory agents. If symptoms

fail to improve, short-term (4-8 weeks) systemic corticosteroid therapy has been successful.

Because the number of drugs with demonstrated clinical activity against MAC is limited, results of susceptibility

testing should be used to construct a new multidrug regimen consisting of at least two new drugs not previously

used and to which the isolate is susceptible from among the following: ethambutol, rifabutin, ciprofloxacin or

levofloxacin, or amikacin. Whether continuing clarithromycin or azithromycin in the face of resistance provides

additional benefit is unknown. Among patients who have failed initial treatment for MAC disease or who have

antimycobacterial drug resistant MAC disease, optimizing ART is an important adjunct to secondary or salvage

therapy for MAC disease.

Adult and adolescent patients with disseminated MAC disease should receive lifelong secondary prophylaxis, unless

immune reconstitution occurs as a result of ART.

Cytomegalovirus is a member of the herpes family of viruses. Majority of infections derive from reactivation of

latent infection.

Retinitis

Retinitis is the most common clinical manifestation of CMV end-organ disease. CMV retinitis usually occurs as

unilateral disease, but in the absence of therapy, viremic dissemination results in bilateral disease in the

majority of patients.

Peripheral retinitis might be asymptomatic or present with floaters, scotomata, or peripheral visual field

defects. Central retinal lesions or lesions impinging on the macula are associated with decreased visual acuity

or central field defects. The characteristic ophthalmologic appearance of CMV lesions includes perivascular

fluffy yellow-white retinal infiltrates, typically described as a focal necrotizing retinitis, with or without

intraretinal haemorrhage, and with little inflammation of the vitreous humour unless immune recovery with potent

ART intervenes. Blood vessels near the lesions might appear to be sheathed. Occasionally, the lesions might have

a more granular appearance.

Colitis

Colitis is the second most common manifestation. It causes fever, weight loss, anorexia, abdominal pain,

debilitating diarrhoea, and malaise.

Esophagitis

Esophagitis caused by CMV occurs in persons with AIDS who develop CMV end-organ disease, and causes fever,

odynophagia, nausea, and occasionally mid-epigastric or retrosternal discomfort.

Pneumonitis

CMV pneumonitis is uncommon, but when it occurs, it presents with shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, a

nonproductive cough, and hypoxemia, associated with interstitial infiltrates on chest radiograph.

Neurologic Disease

CMV neurological disease causes dementia, ventriculoencephalitis, or ascending polyradiculomyelopathy.

CMV viremia

CMV viremia can be detected by PCR, antigen assays, or blood culture and is generally detected in end-organ

disease, but viremia also might be present in the absence of end-organ disease. The presence of serum antibodies

to CMV is not diagnostically useful.

CMV retinitis

The diagnosis of CMV retinitis is generally made on the basis of recognition of characteristic retinal changes

observed on fundoscopic examination by an experienced ophthalmologist.

CMV colitis

The demonstration of mucosal ulcerations on endoscopic examination combined with colonoscopic or rectal biopsy

with histopathological demonstration of characteristic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic inclusions are required

for the diagnosis of CMV colitis.

CMV esophagitis

The diagnosis of CMV esophagitis is established by the presence of extensive large, shallow ulcers of the distal

esophagus and biopsy evidence of intranuclear inclusion bodies in the endothelial cells with an inflammatory

reaction at the edge of the ulcer.

CMV pneumonitis

Diagnosis of CMV pneumonitis should be made in the setting of pulmonary interstitial infiltrates and

identification of multiple CMV inclusion bodies in lung tissue, and the absence of other pathogens that are more

commonly associated with pneumonitis in this population.

CMV neurologic disease

CMV neurologic disease is diagnosed on the basis of a compatible clinical syndrome and the presence of CMV in

cerebrospinal fluid or brain tissue.

CMV retinitis

The choice of initial therapy for CMV retinitis should be individualized. Oral valganciclovir, intravenous

ganciclovir, intravenous ganciclovir followed by oral valganciclovir, intravenous foscarnet, intravenous

cidofovir, and the ganciclovir intraocular implant coupled with valganciclovir are all effective treatments for

CMV retinitis.

CMV colitis or esophagitis

The choice of initial therapy for CMV colitis or esophagitis is intravenous ganciclovir or foscarnet.

CMV neurologic disease

For neurological disease, initiating therapy promptly is critical for an optimal clinical response. Combination

treatment with ganciclovir and foscarnet might be preferred as initial therapy.

Although drug resistance might be responsible for some episodes of relapse, early relapse is most often caused by

the limited intraocular penetration of systemically administered drugs. Because it results in greater drug

levels in the eye, the placement of a ganciclovir implant in a patient who has relapsed while receiving systemic

treatment (IV ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir) is generally recommended.

After induction therapy, secondary prophylaxis is recommended for life, unless immune reconstitution occurs as a

result of ART. Regimens demonstrated to be effective for chronic suppression include parenteral or oral

ganciclovir, parenteral foscarnet, combined parenteral ganciclovir and foscarnet, parenteral foscarnet,

parenteral cidofovir and (for retinitis only) ganciclovir administration through intraocular implant or

repetitive intravenous injections of fomivirsen. FDA has approved oral valganciclovir for both acute induction

therapy and for maintenance therapy.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treating opportunistic infections among

HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes for Health, and the HIV

Medicine Association / Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR 2004; 53(No.RR-15)

2. World Health Organisation. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents in

resource-limited settings: Towards universal access. 2006 revision.

http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/artadultguidelines.pdf Accessed 15,th June 2006.

3. API Consensus guidelines for use of antiretroviral therapy in adults. JAPI 2006; 54:57-74.

4. AIDS. Devita VT, Hellman S and Rosenberg SA, Eds. Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

5. AIDS Therapy. Dolin R, Masur H and Saag MS, Eds. Churchill-Livingstone 2003.