Introduction

50% of children at least wheeze once by the age of 6 years and 40% of them will continue wheezing in later childhood.1, 2

90% of children with increased risk of asthma have been detected with a viral cause for wheezing.4

Globally, about 11.5% and 14.1% children 6-7 and 13 to 14 years of age respectively report wheezing.5

Approximately 50% of children reported current wheeze along with symptoms of severe asthma in Indian subcontinent.5

The cost of treating preschool wheezing in children has been estimated to be 0.15% of the National Health Service budget in the United Kingdom.8

Asthma is considered the most common condition presenting with wheeze and 30% of infants who wheeze go on to develop asthma.2, 9

Definition

Wheeze is a common respiratory symptom, which could represent multiple underlying pathologies. It is a sign of airway obstruction in the intrathoracic airways and defined as a continuous high-pitched sound, with musical quality, emitting from the chest during expiration. It could be an isolated symptom or could be accompanied by other symptoms such as dyspnoea, coughing and chest tightness. Wheezing is considered recurrent if there are three or more episodes in the previous year.

The European Respiratory Society (ERS) Task Force has agreed to not use the term ‘asthma’ to describe wheezing in preschool children as there is insufficient evidence on the pathophysiology.

Risk Factors

Several birth cohort studies have tried to evaluate the risk factors for the development and persistence of wheeze in preschool children. In addition to viral infection, the various risk factors that have been identified in these studies are as follows:

- Maternal smoking during pregnancy/ passive exposure to cigarette smoke

- Family history of atopy and/or lower airway diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Breastfeeding for less than 6 months

- Having siblings and attending day care

- Male gender

- Low birth weight

- Low gestational age

- Congenital heart disease

- Indoor air pollution

- Having a pet at home

- Pneumonia

- Use of antibiotics and paracetamol in the first year of life

More than six episodes of upper respiratory tract infections in early life

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

Wheezing is a symptom for which there could be many aetiologies and the diagnosis of wheezing primarily involves understanding the cause behind wheezing. A careful and thorough history-taking and physical examination are the most important instruments for evaluating the cause behind wheezing.

- The first step is to confirm the parent-reported wheeze as parents could be using the term wheeze to describe a multitude of respiratory sounds that may not actually be wheeze.

- History-taking should consist of understanding the patterns and triggers of wheeze, personal and family history of atopy, and smoking habits of family members.

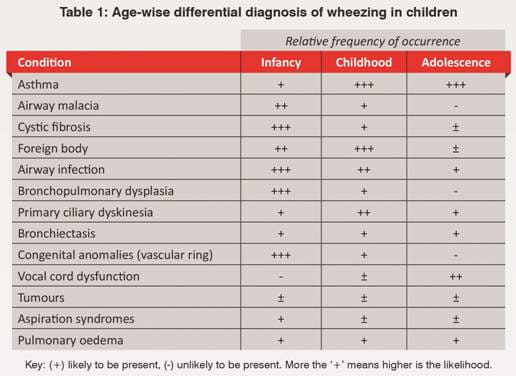

- Differential diagnosis of wheezing should also be considered according to the age of the child (Table 1).

Unless the wheezing is unusually severe, therapy-resistant or accompanied by unusual clinical features, investigations such as chest X-ray, sweat chloride, bronchoscopy, barium esophography, bronchoalveolar lavage, and airway biopsies are not recommended.

Asthma can be assessed by using spirometry and evaluating the bronchodilator reversibility. However, spirometry is not a reliable tool in children less than 5 years of age where there is a higher incidence of wheezing.

Phenotypes

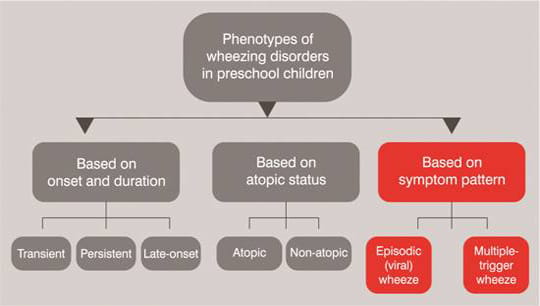

Since recurrent wheezing has a heterogenous natural history, phenotyping in the clinic is a challenging task. Traditionally, wheezing has been classified using the epidemiological and natural history approach (the well-known Tucson cohort study from the 1980s). However, this classification was incomplete as it was based more on the retrospective analysis and, hence, did not elaborate on the management strategies. Hence, in 2008, the ERS Task Force proposed a new classification system based on the temporal patterns of wheeze (a more clinical approach).

Figure 1 describes the old as well as new classification systems. The colour ‘grey’ represents the early classification system while the colour ‘red’ represents the ERS classification system.

Figure 1: Classification of wheezing phenotypes

According to this new classification system, episodic (viral) wheeze is defined as

discrete episodes of wheezing, with the child being well between episodes, and is most commonly associated with a

viral respiratory tract infection. Multiple-trigger wheeze on the other hand is defined as discrete exacerbations

and symptoms between episodes and is associated with multiple triggers such as tobacco smoke, allergens, emotions

and exercise in addition to viral respiratory infections.

Both episodic (viral) wheeze and multiple- trigger wheeze can be further classified as follows:

- Transient: Wheeze appears before 3 years of age and disappears by 6 years of age.

- Persistent: Wheeze continues till 6 years of age or more.

- Late-onset: Wheeze starts after 3 years of age.

Episodic (viral) wheeze mostly declines by the age of 6 but can continue into the school age, change into multiple-trigger wheeze or disappear at an older age. Multiple-trigger wheeze, on the other hand, can persist beyond early childhood and has been associated with a significant reduction in lung function by 11 years of age.

Management

Acute and chronic wheezing need different management approaches. Management also involves non-pharmacotherapy in the form of environmental control such as strongly discouraging exposure to tobacco smoke. Parents should also be educated regularly on the causes of wheeze, treatment and recognizing warning signs.

Device selection

The ERS Task Force strongly recommends that, for drug delivery, a pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI) with a non-electrostatic spacer should be preferred over any other inhalation device, including the nebulizer. For children less than 3 years of age, a facemask with a tight seal over the mouth can be used along with the pMDI+spacer. The ERS Task Force also advises that drug delivery when the child is crying should be avoided as there is reduction in the drug deposition in the lower airways.

Pharmacotherapy

Acute

The ERS Task Force recommends the following for the treatment of acute episodes of wheezing in preschool children:

- Inhaled short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs), excluding single-isomer salbutamol, using a pMDI+spacer, should be used as needed for the symptomatic treatment of acute wheezing in preschool children.

- However, these should be used cautiously in infants since paradoxical responses can occur in this age group.

- Intravenous and oral SABAs should not be used for the treatment of acute wheezing episodes.

- In patients with severe wheeze, addition of ipratropium to SABAs may be considered.

- In preschool children with acute wheeze with severity that warrants hospital admission, a trial of oral corticosteroids should probably be given.

- A short course of oral corticosteroids initiated by parents should not be given.

- High-dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not recommended in the treatment of acute wheezing in preschool children due to the high cost and lack of comparison with bronchodilator treatment, although there appears to be a small beneficial effect with ICS.

Chronic

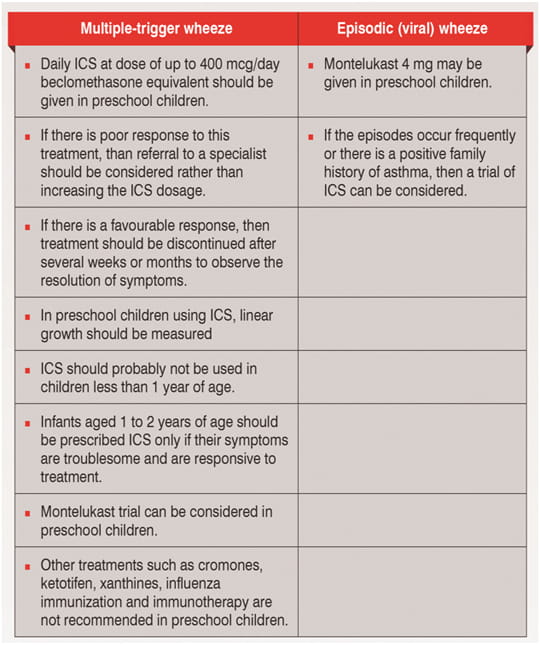

The ERS Task Force has recommended the following treatments according to the phenotypical classification of wheezing

in preschool children:

Predicting Asthma in Children with Wheezing

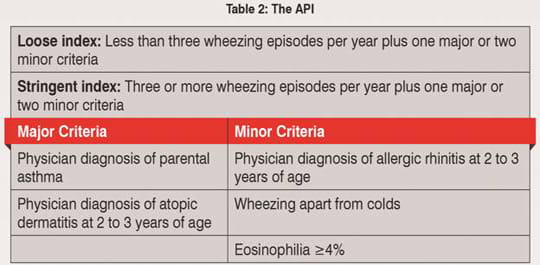

Although not entirely, it is possible to predict which infants with recurrent wheezing will go on to develop asthma with the help of the Asthma Predictive Index (API) (Table 2).

The API is useful to predict the development of asthma at school age after taking into account the risk factors in the first 3 years of life.

Prevention of Wheezing

Although highly desirable, prevention of recurrent wheezing has not been well elucidated

as yet.

The strongest evidence points to the association of maternal smoking and preschool wheeze and, hence, women who are

contemplating pregnancy should be encouraged to quit smoking.

The other approaches that are currently being studied are the use of probiotics and vitamin D supplementation during

pregnancy.

There is some evidence that exclusive breastfeeding and rational use of antibiotics may be protective against

wheezing. However, currently, there are no strong evidence-based recommendations regarding the prevention of

recurrent wheezing in preschool children.

Summary

- Wheezing is very common in the preschool age group.

- There are several risk factors for wheezing, the strongest of which are pre- or post-natal smoking and viral infections.

- Confirmation of parent-reported wheeze is important during the diagnosis of wheezing in preschool children.

- Good history-taking and physical examination are the most important steps for diagnosis.

- Investigations such as chest X-ray, bronchoscopy, sweat chloride, etc., should be used for the differential diagnosis of wheezing.

- Recurrent wheezing can be phenotyped as episodic (viral) wheeze and multiple-trigger wheeze, based on the patterns of wheezing.

- Episodic (viral) wheezing and multiple-trigger wheezing can be further sub-classified as transient, persistent and late-onset.

- A pMDI+spacer combination (with a facemask for children <3 years of age) is the preferred inhalation device for both acute and chronic use.

- The first-line treatment for acute episodes of wheezing is inhaled SABAs.

- Daily ICS can be used for the chronic treatment of multiple-trigger wheeze whereas they can be tried in episodic (viral) wheeze only if the episodes are frequent or there is a positive family history of asthma.

- Montelukast can be used for both episodic (viral) wheeze as well as multiple-trigger wheeze.

- The API can be used to which predict children with wheezing in first three years of life would go on to develop asthma at school age.

Although there is some evidence of using preventive strategies such as avoidance of pre- and post-natal exposure of cigarette smoke, exclusive breastfeeding, rational use of antibiotics, and use of probiotics and vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy, there are no strong recommendations for primary prevention as yet.

References

-

Paediatr Respir Rev. 2011; 12:70–7.

-

Early Hum Dev 2013; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.07.017

-

Indian Pediatr. 2010; 47(1):56–60.

-

Treatment of recurrent virus-induced wheezing in young children. Available from www.uptodate.com [as accessed on 12th November, 2013]

-

Thorax 2009; 64:476–483

-

N Engl J Med 2009; 360 (20):2130–2133

-

Acta Medica Lituanica. 2010; 17 (1–2): 40–50

-

Medicine 2007; 36 (4):191–195

-

Pediatric Reactive Airway Disease. Available from www.medscape.com [as accessed on 12th November, 2013]

-

Thorax 2010;65:1004–1009

-

Asthma By Consensus: Indian Academy of Paediatrics Respiratory Chapter [online]. Available from URL: http://www.iaprespiratory.org/workshoptopics/ASTHMA-BY-CONSENSUS.pdf [as accessed on 23rd January, 2012].

-

Eur Respir J 2008; 32:1096–1110

-

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160:1617–1622

-

J Clin Med Res 2013; 5(5):395–400

-

Allergy 2010; 65:404–411

-

J Asthma. 2013; 50(4):370–375

-

J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013; 89(6):559–566

-

J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 128 (3):690.e1-e5

-

From the Global Strategy for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma in Children 5 Years and Younger, Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) 2009. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/ [as accessed on 23rd January, 2012].

-

Pediatric Health 2010; 4(3):267–275

-

WAO Journal 2010; 3:253–257

-

NZFP 2008; 35 (4):264-269 [online]. Available from www.rnzcgp.org.nz [as accessed on 3rd February, 2014]

-

Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2000; 162:1403–6

-

Paediatr Respir Rev. 2013; 14:46–52

-

Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2009; 9:141–145