Aspects of Asthma: Severe Asthma

Globally, 5-10% of the total asthma population suffers from severe asthma.1,2

Approximately 2 million people suffer from severe asthma in the United States and yet it remains poorly understood.3

The average cost per patient with severe asthma is reportedly six times that of mild asthma.4

Approximately 10% of patients with severe asthma have reported a history of intubation for asthma.5

Medication usage is high in patients with severe asthma, with almost 26% using three or more controllers.5

The mortality rate amongst individuals with severe asthma is estimated to be 6.7 per 100 person - years.19

Definition of Severe Asthma

The term, severe asthma, has undergone several changes in definition since the first attempt by the Global Initiative for Asthma Management (GINA) guidelines in 1995.8 Various societies and organisations such as the European Respiratory Society (ERS), American Thoracic Society (ATS), World Health Organisation (WHO) and Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) have tried to define severe asthma using various terminologies such as ‘difficult asthma’, ‘severe refractory asthma’, ‘poorly controlled asthma’, and ‘uncontrolled asthma’.7

Risk Factors and Contributory Factors

In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in the United States established one of the most comprehensive networks of researchers on severe asthma called the Severe Asthma Research Program or SARP.9 SARP is an ongoing research initiative to understand the mechanisms, phenotypes and characteristics of severe asthma to develop better management strategies for this condition.10

The following are some of the risk factors that have been identified from the various SARP studies so far:

- Female gender11

- Adult-onset11

- Obesity11

- Tobacco smoke exposure11

- Comorbid diseases such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD)12

- History of sino pulmonary infections/sinusitis/pneumonia12

- Aspirin-sensitivity12

Severe asthma is also associated with several comorbidities and contributory factors as listed below:

1. Rhinosinusitis/ (adults) nasal polyps1

2. Psychological factors such as depression, anxiety, personality traits1

3. Vocal cord dysfunction1

4. Obesity1

5. Smoking/smoking-related diseases1

6. Obstructive sleep apnoea1

7. Hyperventilation syndrome1

8. Hormonal influences1

9. Symptomatic GERD1

10. Drugs1

11. Non-adherence1

Identifying Severe Asthma in Clinical Practice

Recognising severe asthma can be quite tricky in real-life practice. Severe asthma has been described as asthma that requires step 4 or step 5 treatment as described in the GINA guidelines–that is, high-dose ICS/LABA to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled or if it remains uncontrolled despite this treatment.14

The word ‘severe’ is also used by the patients’ to describe the intensity or frequency of their symptoms, which may not necessarily indicate a severe disease as it may be possible to control the symptoms using the right doses of ICS.14 Hence, it is quite important to explain the term ‘severe’ to the patient when diagnosing severe asthma.14

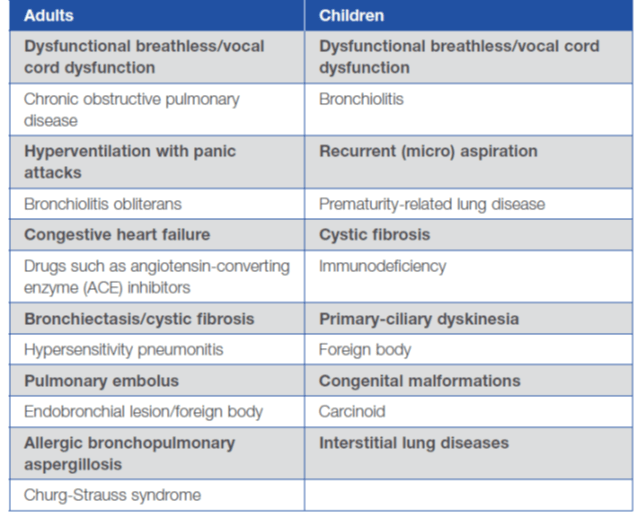

The first step towards diagnosing severe asthma is its differentiation from uncontrolled asthma.14 Uncontrolled asthma is a very common reason for persistent symptoms and frequent exacerbations of asthma and may be easily improved.14 The following problems, which contribute to ‘difficult’ asthma,15 need to be excluded before considering the diagnosis of severe asthma:14

- Ability to use inhalers correctly

- Adherence issues

- Confirmed diagnosis of asthma

- Ruling out the alternate diagnosis of asthma

- Comorbidities and contributory conditions

- Exposure to irritants and allergens

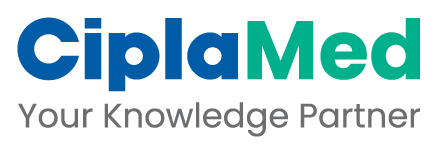

The common differential diagnoses of severe asthma in adults and children are as follows:

One of the key differences between difficult asthma and treatment-resistant/refractory severe asthma is that difficult asthma can be managed by modification of the common problems mentioned above.15 Treatment-resistant / refractory severe asthma probably needs more than the traditional treatment options and, hence, is now the focus of research in the development of targeted therapies in the form of monoclonal antibodies.

Treatment Options for Severe Asthma

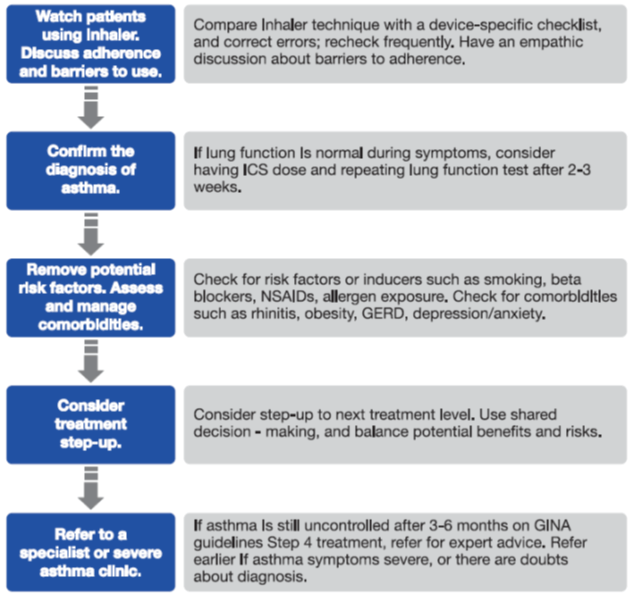

The various international guidelines recommend treating severe asthma with established treatments such as high-dose ICS with or without LABAs and/or oral corticosteroids and/or other additional controllers such as leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs), or theophylline.7,14

The high doses of ICS for the treatment of severe asthma have been defined by the ATS/ERS guidelines on the treatment of severe asthma and are described in Table 1 below.

Severe refractory asthma could be corticosteroid-dependent or corticosteroid insensitive.1 Although it has been observed in various severe asthma clinical trials that these patients may need regular oral corticosteroids or frequent oral corticosteroid bursts, there is no clarity on the timing of the initiation of oral corticosteroids.1 However, the treatment of patients with corticosteroid insensitivity is not very clear yet and is a subject of intense research.

The ATS/ ERS guidelines also recommend the use of sputum inflammometry by eosinophils count to guide ICS treatment in patients with severe asthma.1 Sputum guided treatment, however, needs specialised centres to carry out the sputum induction techniques and, hence, is not available that easily. With regards to using fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) to guide ICS treatment in severe asthma, the ATS/ERS guidelines recommend against it because of very low- quality evidence to support its use.1

Various treatments other than ICS, ICS/LABA, oral corticosteroids, LTRAs and theophylline have been studied in the context of severe asthma, although there are no definite recommendations from the guidelines on their use in routine clinical practice. Some of these have been described below:

- Monoclonal antibodies (mABs): The well-studied, US FDA-approved, commercially available mAB is omalizumab, which is an anti-lgE. Hence, it is mainly recommended in cases of severe allergic asthma that is uncontrolled on Step 4 treatment (high-dose ICS/LABA).14 The new GINA 2016 strategy recommends omalizumab as the preferred Step 5 add-on treatment choice, before initiation of long-term OCS use.6 Subcutaneous omalizumab in moderate-severe asthma has shown a steroid-sparing effect, reduction in exacerbations as well as hospitalisations and an improved quality of life.16

- Tiotropium: Various recently published studies have shown the beneficial effects of adding tiotropium to ICS+LABA in terms of improvement in lung function and decrease in exacerbations in patients with severe asthma.1 Interestingly, however, the recently updated GINA guidelines as well as another published guideline, a collaboration of the Indian Chest Society and the National College of Chest Physicians, recommends adding tiotropium in cases of asthma that stays uncontrolled even after high-dose ICS/LABA treatment.14,18

- Methotrexate: The ATS/ERS guidelines recommend against the use of methotrexate in adults and children with severe asthma to avoid the adverse effects associated with the drug.

- Macrolides: Although there have been some studies that have shown the positive benefits of treating severe asthma, especially the neutrophil predominant phenotype with macrolides such as azithromycin,19 the ATS/ ERS guidelines recommend against the use of macrolides for the treatment of severe asthma.1 This is because of the relatively unclear benefits of the treatment and the risk the developing resistance to macrolides.1

- Antifungals: The ATS/ ERS guidelines recommend using antifungal treatment in patients with severe asthma with recurrent exacerbations of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)1. However, antifungals are not to be used in patients of severe asthma without ABPA even if they demonstrate fungal sensitisation on the skin prick test or serum lgE.1

The non-pharmacological treatment that has been studied in the context of severe asthma is bronchial thermoplasty. The ATS/ERS guidelines do not recommend using bronchial thermoplasty outside the clinical trial set-up, because of insufficient evidence in terms of benefit to the patients.1

The focus of severe asthma research is to now identify the phenotypes or endotypes and develop a phenotype- or endotype-driven treatment. Hence, there has been a lot of stress on identifying the pathophysiological pathways, biomarkers and targeted molecules in the area of severe asthma research.

Phenotypes and Endotypes: A Step Ahead in Personalised Medicine

Severe asthma is not a single uniform entity and its heterogeneity has been recognised with the various research projects characterising phenotyping and, now, endotyping of severe asthma.13

Initial studies have recognised that some consistent features of severe asthma include requirement for high doses of ICS with or without oral corticosteroids, low lung function, daily symptoms and frequent and/or severe exacerbations.13

However, it was also observed that these characteristics are not universal to severe asthma and, hence, the scientific research is focused on phenotyping severe asthma.13

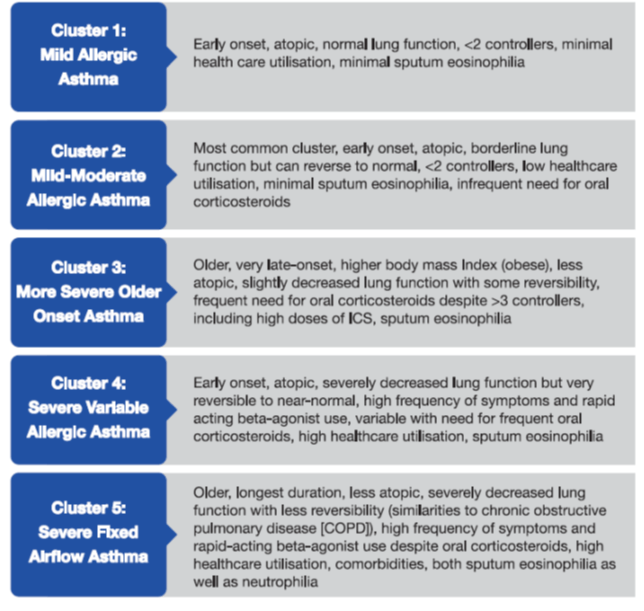

Phenotyping severe asthma involved identifying certain clinical and pathological features.13 For example, various SARP studies identified the following phenotypes of severe asthma.13

1. Early-onset

2. Eosinophilic

3. Neutrophilic

4. Obesity-related

However, it was soon realised that none of these phenotypes provide much insight into the pathogenic mechanisms involved in the development of that particular phenotype.13 Hence, the next logical step was to link pathobiology to the clinical phenotypes and, thus, the current focus of research is identifying the endotypes of severe asthma.13

The term, endotype means ‘a subtype of a condition that is defined by a distinct functional or pathophysiological mechanism’ and involves identifying biomarkers and genes in addition to the clinical and pathological features.13 There have been various studies on severe asthma, which have identified certain endotypes as in Box 1. These endotypes have been identified using a statistical technique called cluster analysis, which, as the name suggests, involves grouping of objects that are similar to each other in some way or the other in the same group, which is known as a cluster.

There is currently a lot of interest in identifying the endotypes of asthma and the work done in this field by SARP is now also being complemented by an European consortium called U-BIOPRED (Unbiased Biomarkers for the Prediction of Respiratory Disease Outcomes).11

Endotyping will help develop more targeted treatments, thus taking a step further towards personalised medicines for asthma.

Targeted Treatments for Severe Asthma

The pathogenesis of severe asthma involves a lot of complex mechanisms and pathways, with numerous mediators playing a role. The recent efforts to develop targeted treatments for severe asthma have led to the evolution of monoclonal antibodies other than omalizumab. Table 2 gives a glimpse of the various molecules studied so far. Of these, mepolizumab (anti-IL-5) and lebrikizumab (anti-IL-13) appear to be the most promising and may soon be commercially available.

|

Target Mediator |

Biomarker |

Inhibitor Molecule |

Clinical Outcome |

|

IL-4/IL-13 |

Blood/sputum eosinophile, serum periostin, eotaxin-3 specific lgE or FENO |

Dupilumab (IL-4 receptor blocker) |

Prevented loss of asthma control |

|

Pitrakinra (IL-4 mutant) |

Improved lung function (FEV1) and symptoms |

||

|

IL-5 |

Sputum/blood/ lung tissue eosinophils |

Reslizumab |

Decreased exacerbations Reduced sputum eosinophils Improved pulmonary function Trend towards better asthma control |

|

Mepolizumab Benralizumab |

Reduced exacerbation rate Reduced eosinophilia improved symptom control and quality of life Reduced oral glucocorticosteroid dose |

||

|

IL-13 |

Total lgE levels, FeNO, Blood eoslnophils, serum periostin, sputum IL-13 |

Lebrikizumab |

Improved lung function (FEV1) |

|

Tralokinumab |

Improvement in pulmonary function Reduction in beta-agonist use No improvement in asthma control |

||

|

IL-17 (A,F,E) |

Sputum/blood neutrophilia |

Brodalumab |

For the overall study population, no differences between treatment and placebo Symptoms and lung function (FEV1) improved in the high-reversibility group

|

|

TNF-alpha |

TNF-alpha expression on peripheral mononuclear cells |

Golimumab |

No improvement in pulmonary function No reduction In exacerbation rate Serious infection risks and malignancies |

|

Etanercept |

Inconsistent results Improvement In pulmonary function and quality of life versus no clinical benefit I misbalanced risk-benefit ratio |

In conclusion, severe asthma is still a relatively unknown entity and, hence, its treatment still heavily relies on the optimal use of the available treatment options. However, the future looks optimistic with regards to the development of targeted treatments such as monoclonal antibodies.

To Summarise:

- Severe asthma constitutes a relatively small percentage of the total asthma population but results in the highest healthcare utilisation associated with asthma.

- Severe asthma is basically recognised as asthma that is refractory to the highest possible level of treatment as recommended by the guidelines.

- There are various risk factors and contributory factors that have been associated with severe asthma, such as obesity, GERD, rhinosinusitis, etc.

- While diagnosing severe asthma, it is first essential to distinguish it from uncontrolled asthma and difficult asthma by ensuring correct inhalation technique, adherence, identification and treatment of comorbidities, and minimising exposure to irritants and allergens.

- Treatment of severe asthma involves using high-dose ICS or ICS/LABA with or without oral steroids and/or LTRAs, theophylline and tiotropium.

- Omalizumab can be considered for allergic severe asthma; however, other treatments such as methotrexate, macrolides and bronchial thermoplasty are not recommended in the regular treatment of severe asthma.

- Antifungal agents should be considered for patients with severe asthma having recurrent exacerbations of ABPA.

- The focus of severe asthma research is to identify phenotypes and endotypes in order to develop more targeted treatments.

- Phenotyping and endotyping involves considering pathological characteristics such as inflammatory patterns, lung physiology and treatment responsiveness in addition to the clinical characteristics.

- Various targeted treatments such as anti-IL5 and anti-IL13 are under development and may herald a new era in severe asthma treatment.

References:

1. Eur Respir J 2014; 43:343-373

2. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/774254_2 (as accessed on 27th January 2015)

3. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 2015; 10:511-45

4. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162:2341-2351

5. J Allergy Clin lmmunol 2012; 130:332-42

6. Global Initiative for Asthma Management (GINA) guidelines: 2016

7. Eur Respir Rev 2013; 22:227-235

8. J Allergy Clin lmmunol 2010; 126:926-38

9. J Allergy Clin lmmunol 2007; 119:14-21

10. www.severeasthma.org (as accessed on 31st March 2015)

11. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185 (4):356-362

12. J Allergy Clin lmmunol 2007; 119:405-13

13. Clin Exp Allergy 2012; 42(5):650-8

14. Global Initiative for Asthma Management (GINA) guidelines: 2015

15. Thorax 2011; 66:910-917

16. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 1:CD003559

17. Chest. 2014. doi:10.1378/chest.14-1698. Online first (16th Oct 2014)

18. Lung India 2015; 32 (Supplement 1):S3-S42

19. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2014;20:95-200