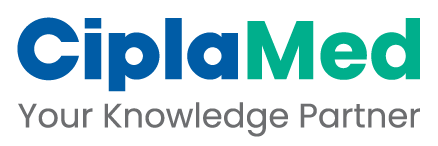

Throughout the world in the last 30 years there has been a steady, relentless increase in the prevalence of childhood asthma. According to the 50-nation International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC):

Long-term Outcome of Childhood Asthma

Long-term Outcome of Childhood Asthma

Introduction

- Asthma is a very common condition.

- Its prevalence varies widely from country to country.

- At the age of six to seven years, the prevalence ranges from 4 percent to 32 percent. The same range holds good for ages 13 and 14.

The UK has the highest prevalence of severe asthma in the world. (Fig. 1)

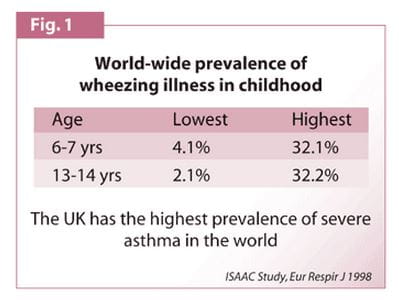

In India, a questionnaire-based study measured the prevalence of asthma in nine randomly selected Delhi schools. The prevalence of current asthma was found to be 11.9 percent. Assuming Delhi represents the whole of India, this means there are 40 million children in India, who suffer with asthma. (Fig. 2)

Outcome of Childhood Asthma

Do children outgrow their asthma or do they just outgrow their paediatrician and pass the problem on to someone else?

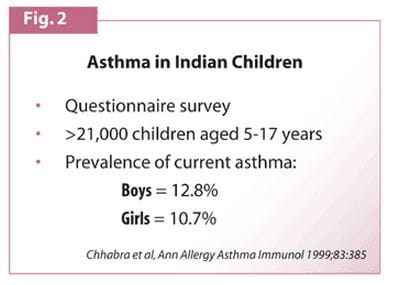

The 1958 Study

A longitudinal prospective study was conducted in UK in 1958. A large cohort of babies, all born in the same week, were gathered and followed during their growth into adulthood. Wheezing and asthma were observed as they grew. The study showed the following results

- At age seven, one half of these children had onset of wheezing, diagnosed as asthma

- By age 11, the wheezing had fallen below 20 percent

- During mid-teens and early 20s, it fell to 10 percent

- By 33 years, relapses occurred after prolonged remission of childhood asthma (Fig. 3)

This epidemiological study looked at asthma overall and did not categorise the cases into mild, moderate, or severe.

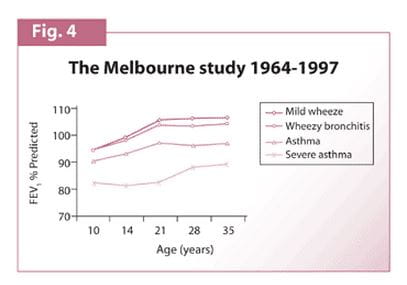

The Melbourne Study

Another study initiated by Dr. Harvard Williams in 1964 in Melbourne overcame these drawbacks. The study covered the age group of 10 to 35 years. Lung function tests were conducted and the children were categorized into four groups:

- Those who had very mild wheezing and only occasional wheezing episode.

- Those who had wheezy bronchitis.

- Those who clearly had asthma.

- Those who had severe asthma.

Tests revealed that in children with mild asthma, lung function improved and early adulthood was normal. However, in children with severe asthma, lung function remained abnormally low even after they grew up.

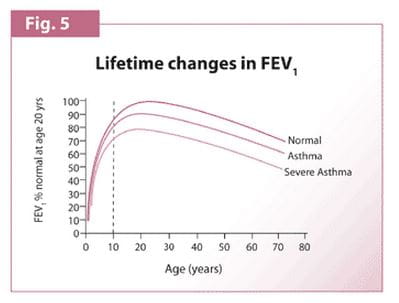

The above graph (Fig. 5) shows the lifetime changes in lung function.

In normal, healthy individual lung function increases up to 20 years of age. Then it declines slowly. In a patient of asthma, maximum lung function is not achieved. Even if the natural decline in lung function is at a normal rate, it will remain lower than that of a normal, healthy person.

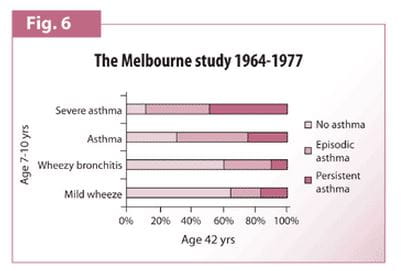

The children participating in the Melbourne study were 10 years of age in 1964 and did not get modern treatment. So, what happens to children who get asthma at the age of 10 and who do not get proper, modern treatment? (Fig. 6)

In Figure 6, there are four categories

- Mild wheeze

- Wheezy bronchitis

- Asthma

- Severe asthma

The vertical axis represents the group of children between the age of seven and ten years. The horizontal axis shows the outcome in their mid-life. The outcome is represented as percentage of subjects with:

- No asthma.

- Episodic asthma.

- Persistent asthma.

The graph shows that 70 percent of those who had mild wheeze completely grew out of their asthma by the age of 42 years. Severe asthmatics had asthma throughout their lives with half of them continuing to suffer from persistent asthma.

Asthma Phenotypes in Children

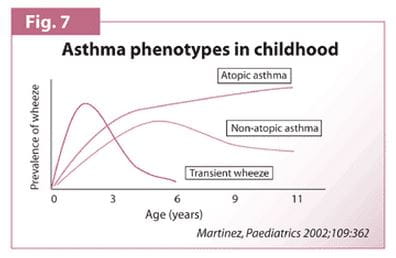

Prof. Martinez and his colleagues studied a cohort of over 1000 newborn babies and followed them very closely throughout their childhood. They paid special attention to respiratory infection & wheezing illnesses.

In Group I, they observed that many children who had started wheezing in the first three years of life stopped wheezing by the age of six or by school age. Prof. Martinez called them transient wheezers. They exhibited the following characteristics:

- They wheezed only when they had viral infections.

- Lung function tests at birth showed narrow airways which were not associated with allergy or atopy. But there was a strong association with maternal smoking during pregnancy.

So the hypothesis was that smoking during pregnancy interfered with the normal development of the lung airways. These tended to be smaller at birth but grew larger with age. By age six, the airways were significantly large and the children were no longer wheezing. In the study, this represented 40 percent to 60 percent of pre-school children who wheezed. In Group II, children had persistent wheezing that was clearly associated with allergy. They wheezed till the age of eleven. Other important characteristics displayed by this group included:

- 60 percent had started wheezing before the age of 3.

- 80 percent before the age of 6.

These children were recognized as children with persistent atopic asthma. Their asthma developed before they went to school and in many of them, before they were 3. In Group III, children had persistent symptoms but were not atopic. The cumulative prevalence increased in the first six years but then started to decline. So, the prognosis in these children was much better although they behaved in very much the same way as atopic asthmatics during the pre-school years.

Looking at all three groups (Fig. 7) their ages overlap and the prevalence is about the same. That poses a challenge to distinguish these children and to predict those who will go on to have persistent wheezing. Those who had persistent wheezing with atopy nearly got over their wheezing in their teens. Those in whom persistent wheezing was not associated with atopy often remitted at school age. This group represented 50 percent to 60 percent of pre-school wheezers.

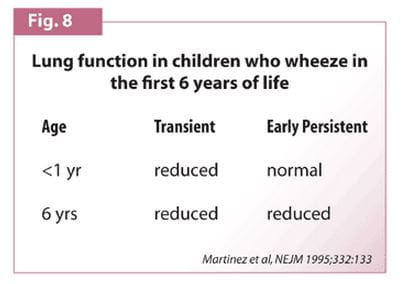

Lung Function in Childhood Asthma

A prospective study conducted in 1995 investigated the factors affecting wheezing before the age of three and their relation to wheezing at age six. The study revealed that the majority of infants with wheezing had transient conditions associated with diminished airway function at birth. They were also at increased risk of suffering from asthma or allergy later in life. In a substantial minority of infants, however, wheezing episodes were probably related to predisposition to asthma. Such children already had elevated serum IgE levels during the first month of life and had substantial deficits in lung function by the age of six. (Fig. 8)

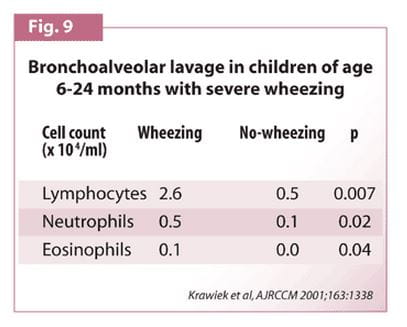

Bronchoalveolar Lavage in Children Aged 6-24 months with Severe Wheezing

In a study carried out in children less than two years of age with early persistent atopic wheezing, bronchoalveolar lavage was done to assess inflammation. Fluid was taken from the airways to detect inflammatory cells. Data obtained from atopic wheezing children was compared with that from children without wheezing. There were increased lymphocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils in wheezing children compared to non-wheezing children. Thus, in wheezing children airway inflammation was apparent by the age of two. Perhaps the outcome of this study gives us a hint about when to really start anti-inflammatory therapy. (Fig. 9)

Risk Factors for Persistent Asthma

- Family history of atopy

- Eczema

- Allergic rhinitis

- Severe symptoms with hospital admission

- Exposure to tobacco

Modification of Long-term Outcome of Childhood Asthma

Three factors have a significant influence on the long-term outcome of childhood asthma:

- Avoiding allergens

- Anti-inflammatory therapy

- Tobacco smoke

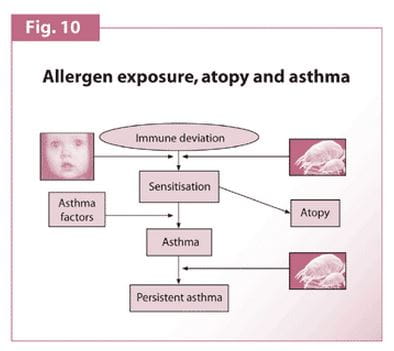

Avoiding Allergens

Allergen avoidance is not new in asthma. The first recorded incidence was way back in 1550. John Hamilton was an archbishop in Scotland who had bad asthma. Gerolamo Cardano was summoned to Scotland to see if he could help. He advised the archbishop to get rid of his feather bedding, feather pillows and cushions and replace them with elementary, hard stuff. Soon, there was a miraculous remission of his asthma.

Allergen exposure is a complex subject. Different things happen in the first or second year and later in childhood. The susceptibility to develop allergy and sensitisation to environmental allergens are genetically determined. There are some individuals who are more predisposed to developing allergy compared to others. This characteristic is described as 'deviation'.

If someone is so inclined genetically, then he is likely to become sensitized to the allergens to which he is exposed. For example, a person from England is likely to become sensitized to house dust mite or to the cat if he has a pet cat. A person from Arizona is more likely to be sensitized to cockroaches. Some studies indicate that exposure to pets in very early life and indeed exposure to farm livestock may actually protect against the development of asthma. Perhaps, in some patients the exposure to an animal allergen in early life may induce immunotolerance. A more likely second mechanism could be that the greater exposure to microbes and infections in early life drives the immune reaction towards an infective type of reaction, thus protecting from developing allergy.

However, if a child becomes sensitized, it does not necessarily mean that he will develop asthma though he may show IgE or allergy mediated responses to the allergens. There are other factors, genetic or environmental, that contribute to the development of asthma. Once the child has got asthma then further allergen exposure is more likely to aggravate the condition and lead to persistent and perhaps more severe asthma.

Hence allergen avoidance is important. This can be achieved by reducing the allergen load. The load will depend on where the child lives. (Fig. 10)

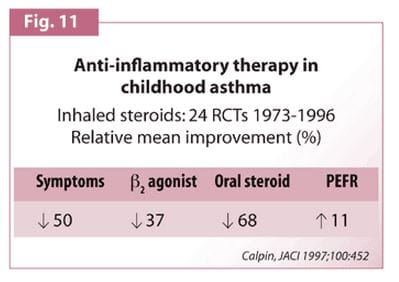

Role of Anti-Inflammatory Therapy

- Inhaled steroids are one of the most potent anti-inflammatory agents available to treat children with asthma. As many as 24 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of inhaled steroid therapy were conducted around the world between 1973 and 1996. The trials revealed that inhaled steroids resulted in:

- 50 percent average improvement in symptoms

- 40 percent reduction in bronchodilator use

- 70 percent reduction in oral steroid use

- Good improvement in lung function, more than 10 percent or 38 L/min of predicted.

- So there can be no doubt that inhaled steroids are highly effective in asthma and that too in low doses. (Fig. 11)

Asthma Treatment Made Easy by Inhaled Corticosteroids

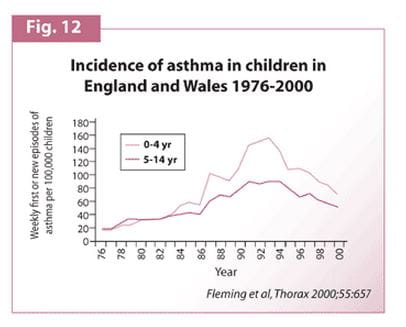

From the mid-1970s to the early 1990s, there was a relentless rise in the incidence of asthma attacks in children throughout the UK. Since 1992-93 there has been a fall in the frequency of asthma attacks. There can be two reasons for this fall:

- Increased use of inhaled steroids to treat early asthma in pre-school children

- Development of teams of highly trained respiratory nurses who train children and parents, the correct use of inhalers.

The fall is not only seen in the asthma attacks treated at home but also in the number of hospital admissions. (Fig. 12)

The Lester Study

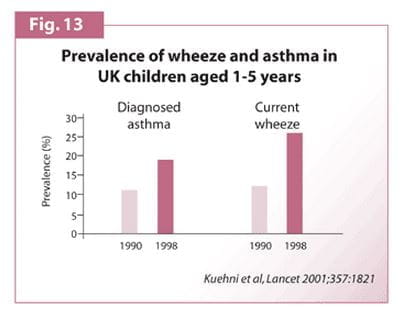

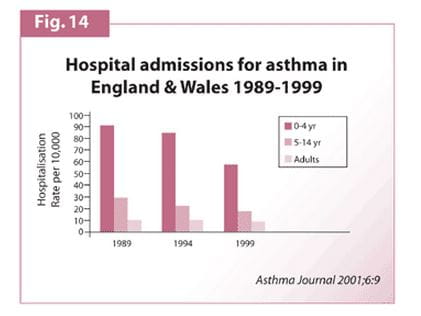

A study in Lester, a middle part of England, showed that the prevalence of diagnosed asthma and apparent wheezing in children aged between one and five years has doubled over the last ten years. Yet, there has been a reduction in asthma attacks and hospital admissions. (Fig. 13 & Fig. 14)

This provides indirect but powerful evidence that the change in treatment and the change in approach to teaching correct inhaler usage has influenced asthma outcome in children. Also the new evidence-based guidelines published by the British Thoracic Society say that inhaled steroids are the most effective controller drugs for children. The strongest possible evidence, covering children of all ages, backs this.

Between 1950 and 1960 steroids were first introduced to pre-school children. These were oral steroids, but were very costly. The children did not grow properly.

Systemic steroids seriously impair growth rate. This concern persists despite the change of delivery route from injection to oral to inhalation. This is a matter of concern to parents and doctors both.

Normal Growth in Children

Normal growth in children is divided into three phases:

Phase I: From infancy up to two years

- Growth is determined by the nutritional state in utero and often at birth.

- Not influenced by hormones such as steroids.

Phase II: Mild childhood growth

- In this phase, growth hormones, thyroid hormones and other hormones come into play.

Phase III: Pubertal growth

- Pulses of androgenic steroids drive the spurt in growth during this phase.

Normal Growth and Asthma

Henry Hyder Solter was a physician who had bad asthma. He practised in London and Edinburg. He wrote very wisely and almost prophetically about asthma in children. One of his most important statements was: "If asthma has come on young in a child he is generally below the average height." This was 100 years before anyone thought about using steroids to treat asthma in children.

Asthma itself impairs growth. It has two important effects on the normal progression of growth in childhood:

- Uncontrolled or inadequately treated asthma affects sleep and therefore the release of growth hormone during the night and early morning.

- Children with asthma often go into puberty late, usually a year or two behind the normal child. Uncontrolled asthma impairs their attainment of normal final height.

Normal Growth and Inhaled Steroid

Over the last 30 years, more than 360 studies conducted, have looked at growth systematically. These have provided certain criteria for inclusion while analysing the effect of inhaled steroid:

- Growth should be studied for at least one year.

- Measurements should be taken properly.

- Control group should be included.

- Confounders (Factors such as asthma severity and control) should be taken into account. (Fig. 15)

Applying these criteria, the number of eligible studies works out to 18.

Different Types of Inhaled Steroids

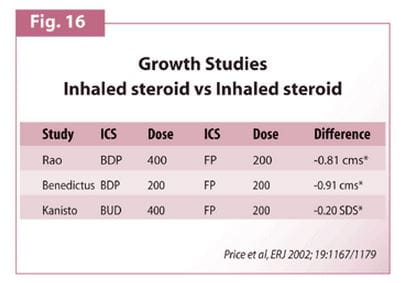

Studies conducted by Rao and Kanisto compared 400 mcg of beclomethasone or budesonide with 200 mcg of fluticasone. The results indicated more rapid growth with fluticasone than with beclomethasone or budesonide. However, none of the inhaled corticosteroids appeared to affect final height. (Fig. 16)

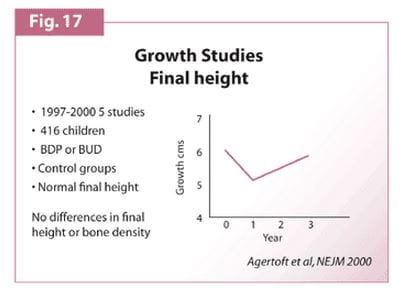

We have been using inhaled steroids in children for the last 30 years and have not seen any retardation in the final adult height. In an analysis of five studies, all published in the recent five years, that used beclomethasone or budesonide but no fluticasone, children attained normal final height.

In another long-term prospective study, children received 400 mcg to 500 mcg of budesonide per day for an average of nine years. Compared to those who did not receive inhaled steroid, there was no difference in final height or in bone density. This is very reassuring data. This study was longitudinal and measurements were done every year. Growth during the first years of inhaled steroid treatment showed a reduction. But then it caught up and accelerated. So, although there was a transient suppression of growth rate in the first year, the children caught up or continued growing for a longer period to achieve a normal final height. (Fig. 17)

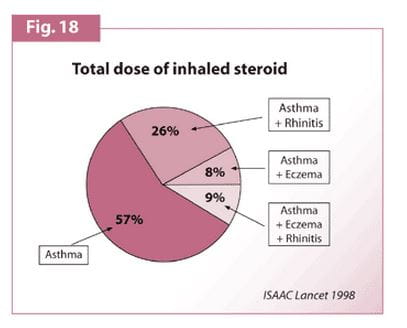

Many children who have asthma tend to have other atopic diseases as well. Only about 60 percent of children have only asthma. A quarter of them have asthma and rhinitis. Nearly 10 percent of them have asthma and eczema while another 10 percent have all three atopic diseases.

All atopic diseases can be potentially treated with topical steroids. There is a transient reduction in growth rate with 400 mcg beclomethasone given into the lungs. There is a similar repressive effect when the same dose of inhaled steroid is given into the nose.

A study undertaken to assess the effects on growth of one year of treatment with intranasal beclomethasone, showed that the children grew more slowly than those who did not receive the steroid. Care must be taken while considering combinations of topical inhaled steroids in children with more than one atopic disease as the drugs can have a cumulative effect. (Fig. 18)

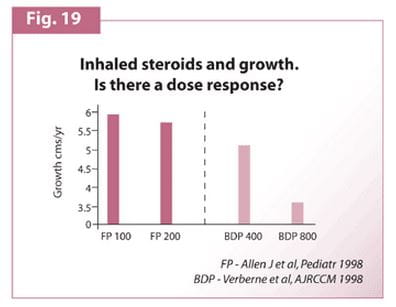

Fig. 19 shows growth rate in children receiving beclomethasone 400 mcg a day. If the dose is increased to 800 mcg a day, growth is slowed further. There should not be any second thought regarding the effects of a dose exceeding 400 mcg a day because there is hardly any. Nor is there any evidence of growth suppression at a dose of 200 mcg a day. However, the dose of 400 mcg a day must be exceeded with care.

Add-on Therapy

If the child's asthma is not well controlled on 400 mcg a day of beclomethasone or 200 mcg a day of fluticasone, then what should be the course of action? It is best to add a drug that has an additive effect with inhaled steroids. There are 3 such classes of drugs:

- Long-acting-beta2 agonist.

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists

- Theophylline.

The most effective of these in school children, are the long-acting-beta2 agonist. However, there are no trials in pre-school children. Although there is less strong evidence in support of using leukotriene receptor antagonists, there are studies in pre-school children. So this is the drug that can be used as add-on therapy in the child under the age of four or five.

Theophylline is less effective. We have less data regarding its efficacy particularly during exacerbations. Also, it has a high risk of side effects. Therefore, long-acting-beta2 agonist and leukotriene receptor antagonists are preferable to theophylline as add-on therapy.

Adolescence and Asthma

The adolescent group with asthma is a difficult group to handle. Teenagers tend to be difficult and usually have problems getting along with others. From the medical point of view, the consequences of this in a teenager with asthma are:

- Underdiagnosis

- Undertreatment

- Increased risk of death.

Tobacco Smoking

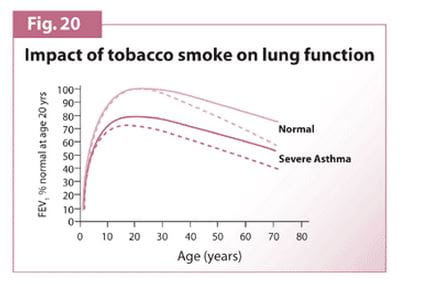

The risk of death in a 15- to 20-year-old with asthma is six times more than that in a 5- to 10- year-old. Given the risk-taking behaviour of the teens, many children with asthma tend to take up smoking like their disease-free fellow teenagers. In the UK, this behaviour is more in girls. Girls grow into women and women have children. The impact of tobacco smoking is so much that if a normal child takes up smoking there is a more rapid decline in lung function in adult life. If a severe asthmatic takes up smoking, that effect is more dramatic and superimposed on an already abnormal lung function. (Fig. 20)

Conclusion

- Airway inflammation and consequent deterioration in lung function occurs in early childhood.

- Allergen exposure aggravates the progression of asthma.

- Passive and active smoking has additional adverse effects on lung function.

- Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of history but may require trial treatment

- Low dose inhaled steroid treatment is ideal for children with persistent symptoms.

- Add-on therapy should be tried before increasing inhaled steroid dose above 400 mcg (beclomethasone).

- Better communication leads to better compliance.

- If asthma is attacked early in childhood, with the right treatment, then children can lead a happy life and progress to normal adulthood.

Questions and Answers

Various issues relating to Childhood Asthma Management were discussed during the question and answer sessions. We present below a compilation of some key queries which were addressed.

Q. How do we Diagnose Asthma in Children Less than Five Years of Age Who Present with Recurrent Wheezing? One of the Markers Mentioned is Exhaled Nitric Oxide. What is the Value of Estimating Exhaled Nitric Oxide in Children with Asthma? Is it a Sensitive Test for Both the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma?

No, it is not a useful test in the diagnosis of asthma. There is no doubt that if you have airway inflammation the level of nitric oxide in your exhaled breath goes up. If you undergo treatment with inhaled steroids the level goes down. But that is a general statement. There are children with severe asthma who have normal levels of nitric oxide. There are people with respiratory infections who have high levels of nitric oxide but do not have asthma at all. So it can at best be a supplementary aid to diagnosis. It may not be sensitive or specific for use in routine management, even if we can afford the equipment and persuade the children to use it.

Q. Is there any Non-Invasive Test for Diagnosing Bronchial Inflammation?

Yes, nitric oxide is one and eosinophil cation protein is another. But they are neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific to be used in clinical practice. Ultimately, airway inflammation can be determined only by bronchoalveolar lavage or bronchial biopsy, which is not advocated in routine practice.

Q. Subclinical Control of Inflammation Leads to Chronicity. How does One Monitor if Inflammation is Fully Controlled or Not?

There is no good non-invasive method of assessing ongoing airway inflammation in children. The non-invasive methods that have been used such as exhaled nitric oxide, the products of eosinophils, and so on are not sufficiently reliable to use in clinical practice.

So in the case of the child who becomes completely and genuinely asymptomatic (including full range of exercise tolerance), first reduce the dose of inhaled steroids and then stop it. If asthma returns over the next few weeks, it will indicate that airway inflammation persists. Then restart inhaled steroids. Parents in general will agree because they would have seen the consequences of stopping it.

Q. What are the Highlights of Hygiene Hypothesis in Asthma?

The basis of the hypothesis is that an exposure to microbes, bacteria or virus, in early life may have a protective effect against the development of asthma. During development, certain types of TH-1 and TH-2 cells are produced. TH-1 cells are directed towards infection while TH-2 cells produce chemical compounds related to allergy. In early life, there is an option to go either way towards TH-1 or TH-2. The theory is that if you are exposed to a lot of something in bacteria or virus, that drives you towards the infective type of response and protects you from allergens.

Children who get a lot of viral infections in early life seem to be protected from getting asthma. Children who are youngest in a large family or children who go to the cr che or nursery at a very early age are exposed to these infections. That is the first piece of evidence.

The second piece of evidence shown by some studies is that if you have a pet at home in the first year of life, that seems to have a protective effect against the development of asthma. The theory is that, microbes that the pet brings with it override the risk of developing allergy to the pet. The stronger evidence coming from six different countries is that children brought up on a farm and who live very close to farm animals during the first year or two of life are very less likely to develop asthma. It is on account of exposure to something in animals. The hygiene hypothesis suggests that it is exposure to dirt but more likely due to exposure to microbes around the place. We are not sure what is in those microbes. The current hypothesis is that it is endotoxin.

Q. What are the Differences Between Asthma in Children and Asthma in Adults?

There are very important differences. Indeed, most asthma in adults starts at childhood. The most important difference is that, paediatricians get an opportunity to treat asthma before airway remodelling or airway inflammation becomes chronic. Paediatricians have the opportunity to diagnose it first and see the early stages of asthma.

There are other important differences too. Childhood asthma is changing all the time. As children grow, some outgrow their asthma, while in some others it becomes worse. The triggers are also different.

Children are more active than adults. So exercise- and activity-induced triggers are more important and have a greater effect on quality of life compared to adults. Pre-school children experience more viral upper respiratory tract infections than adults. In children, these are major triggers of asthma attacks whereas in adults they are not.

Q. Does Theophylline Work as Preventer?

Yes, but not very well. Theophylline given in low dosages regularly has some anti-inflammatory effect and some bronchodilatory effect. But it is very much a second choice and not to be used unless there are very good reasons or better options available.

Q. What is Cough-Variant Asthma in Pre-School Children?

There is a lot of work done on this by S. McKenzie in London, UK. It was concluded that less than 10 percent of pre-school children had cough. Rest of them would have wheeze which their parents might know or would be diagnosed by the doctor through provocation. The provocation in a pre-school child is to make him run up and down and then listen to the chest. While cough variant asthma is very uncommon it does exist.

Q. What Makes One think of Cough-Variant Asthma?

The child is thriving, cough occurs only at night and with exercise, but is not productive with purulent sputum. There is no other diagnosis. The doctor should then observe if the cough goes away with asthma treatment.

Q. What is the Effect of Long-Term Inhaled Budesonide Greater than 400 mcg or 800 mcg on the Growth and Height of the Child?

The important answer is that if one uses a dose too high for the severity of asthma, then one may get growth suppression. If the dosage is appropriate according to the severity of asthma, then there is very little risk of growth suppression.

Q. What is the Duration of Therapy and Role of Immunotherapy?

Judgement should be made about treatment every two months. If the child becomes asymptomatic on inhaled steroids, reduce the dose. Once the dose becomes the lowest possible and the child remains asymptomatic, stop the drug. If symptoms return and the parents agree that the child needs treatment, restart medication.

There is no place for immunotherapy in practice.

Q. Do Children Really come off Treatment Permanently?

Some will come off permanently, because in some children asthma remits spontaneously. There is, unfortunately, no way of predicting this. So when the child becomes asymptomatic wean them off treatment and see if asthma comes back.

Q. Is a Spacer Device better than a Nebuliser?

If high dose nebulised bronchodilator is used for acute asthma in a child under the age of five, there is a possibility that the oxygen saturation may fall. If a high dose of salbutamol is given by spacer, this does not happen. In general practice, it is better to carry a spacer rather than a nebuliser when going on visits.

Q. At What Age can Inhaled Steroids be given?

One can give inhaled steroids at the age asthma is diagnosed. And one can even diagnose asthma in infancy provided the symptoms are frequent and severe enough to justify treatment.

There is no bottom age limit but one must assess the frequency and severity of symptoms, and other associated features that may suggest that asthma will persist. But inhaled steroids can be started in a child of just six months if these criteria are met.

Q. Is there any Scope for using the Oral Bronchodilators - Salbutamol and Terbutaline a in Acute Asthma?

In India many oral preparations of both these are available. Maximum bronchodilatory effect is reached in five to ten minutes with inhaled salbutamol. Oral salbutamol takes 30 minutes. There is no place for oral medication in acute asthma unless the child is totally unable to take inhaled steroids by any means available.

Q. What is the Role of Montelukast and Zafirlukast in the Control of Asthma? Do they have a Steroid-Sparing action?

The role of montelukast in the management of childhood asthma would evolve over the next few years. Montelukast is recommended in school children of five years and above in whom low doses of inhaled steroids combined with long-acting beta agonists have failed to control asthma. So it is a second choice add-on therapy. In pre-school children with persistent symptoms not controlled with low dose inhaled steroids, montelukast is the first line add-on therapy, as long-acting beta agonists do not have a licensed number of trials. In the USA, montelukast is used as a first line anti-inflammatory therapy. In the UK, the drug is not recommended, as there is no evidence to justify it and also, the drug has not been around long enough. For short-term use (say two years) it is an extremely safe drug.

Q. In our country lots of Children are Breast-fed in Infancy. Are there any Studies dealing with the Long-Term Outcome of Asthma in Breast-Fed and Non-Breast-Fed Children?

There is no evidence that breast-feeding reduces the prevalence of asthma or affects its long-term outcome. There are many other very good reasons for breast-feeding but unfortunately no claims can be made in terms of asthma.

Q. Does Exercise, especially Swimming, along with other Preventive Measures have a Beneficial Effect on the Long-Term Outcome of Asthma?

Exercise is vitally important for children with asthma. It won't affect the long-term outcome but it will certainly improve their capacity for coping with asthma and also improve their quality of life. Swimming is particularly a good exercise for children with asthma. Do encourage all children with asthma to exercise regularly.

Q. What is the Role of Diet in Asthma? Is there any Evidence suggesting the Use of Omega 3-Fatty Acids and Fish Oil Supplements in Asthma?

In a study conducted in London 10 years ago, doctors Michael and Nicholas Wilson noted that children who had cold and fizzy drinks were more prone to asthma attacks. The study involved English children and Indian children living in London. They all were given a cold or fizzy drink and the responsiveness of the airways was tested with histamine challenge before and after. It was found that in 20 percent of the English children and 70 percent of the Indian children, the lung airways became more reactive after a cold or fizzy drink. The results of that study prompted doctors to advise parents (particularly Indian parents living in England) that cold and fizzy drinks might increase the risk of their children having asthma attacks.

As regards omega 3-fatty acids there is not much to say. There are few studies being published. It is very interesting work a both the work on fatty acids and work on antioxidants. These studies have just begun to suggest that they may affect development of asthma.

Q. Does Pollution have any Role in Increasing Asthma?

Pollution does not increase incidence. This has been clearly shown by the German study that compared the incidence of asthma in highly polluted and dirty East Germany and the very clean West Germany. It was found that asthma was more common in middle class West Germany compared to East Germany. So prevalence is not affected by outdoor pollution but the severity is. If a child is already an asthmatic, living in a polluted area it increases the risks of asthma attacks. In other words, polluted atmosphere makes asthma worse.

Q. The Dose of Inhaled Steroid has Something to do with the Growth. Is there any Relation with Duration of Therapy? Is there Place for Short-Term Therapy Followed by a Break to Prevent any Possible Effect on Growth?

There is no evidence of any relation between duration of therapy and growth. Growth is exclusively related to dose. And at low doses, considered to be appropriate doses, there is no danger of growth suppression in the long-term.

Q. Apart from the Effects on Growth are there any Side Effects like Local Atrophic Effect on the Epithelium?

There are no reports of side effect other than local atrophic effect on the epithelium. Bruising inside has not been reported in children treated with appropriate dose of inhaled steroid. Only when large doses are used for long period of time suppression of the adrenal gland might be seen.

Q. Long-Term Steroid Inhalers are not Recommended in Mild Intermittent Asthma. Are there other Drugs that Prevent Recurrence of Mild Intermittent Asthma?

The one word answer is NO. There are no drugs to prevent mild recurrent asthma. If a child has mild intermittent asthma and has only occasional symptoms we just have to treat symptoms when they occur. What should be done is to treat them with bronchodilators. If the attacks are severe but intermittent then treat with short courses of oral steroids. One class of drugs that might prove to be useful in this situation is the leukotriene receptor antagonists. Potentially, they may prevent intermittent mild asthma. However, studies have not been done yet, so we don't know for sure.

Q. What is the Highest Dose of Fluticasone Recommended in Children?

The highest recommended dose is 400 mcg a day in severe asthma. One rarely needs to go to that dose. In general, patients are very effectively treated with 100 to 200 mcg a day, some of them even with only 50 mcg a day. There may be a very small number of children who do not respond to a standard dose of inhaled steroid combined with any other add-on therapy. Only in these children will we need higher doses. It is important to balance the possible risks of high dose inhaled steroids against the absolutely certain adverse effects of uncontrolled severe asthma. The highest dose of fluticasone that has ever been given is 1000 mcg a day.

Q. What is the Percentage of Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists that is Used and How Frequently?

As much as 75 percent of the children whose asthma is not controlled by low doses of inhaled steroids benefit by adding a long-acting beta agonist. We can give a leukotriene receptor antagonist to the remaining 25 percent. In the pre-school child where long-acting beta agonists are not licensed for use, prescribe a leukotriene receptor antagonist as first line add-on therapy. One other place where leukotriene receptor antagonists are used is where parents absolutely refuse to allow their child to have inhaled steroids.

Q. Leukotriene Receptor Antagonists and the Long-Acting B2-Agonists have been Recommended as Add-On Therapy. How Long should they be given?

The treatment of a child who is receiving that sort of a combination therapy should be reviewed every two months. If the child becomes asymptomatic during that period, reduce treatment. Now the next question is which one should be reduced first? Always reduce the inhaled steroid first. After reducing the inhaled steroid, if the child remains asymptomatic then stop the add-on therapy. Take these decisions at an interval of two months.

Q. What has been the longest observational study of fluticasone usage in children particularly with reference to its effects on growth?

As fluticasone has been available in the UK for the past 10 years, we have 10 years of clinical experience of fluticasone in children. The longest published well-designed clinical trials have been for over two years. And the data is that there is suspicion of a small degree of growth suppression at 200 mcg a day in school age children. However, at less than half centimetre a year, the suppression is half of that seen with 400 mcg a day beclomethasone or budesonide. There are no studies of children treated with fluticasone throughout their childhood to look at their final height.

Q. Is there Any Role for Anti-Allergic Therapy like Cetirizine or Loratadine Especially for Lowering the Incidence of Long-Term Asthma?

There is little evidence that anti-allergics, even those with anti-anaphylactic properties like ketotifen, are directly useful in the treatment of asthma. However, these drugs are effective in the treatment of rhinitis. It is important to treat allergic rhinitis if it co-occurs with asthma. It may indeed indirectly affect asthma. It is good to use these drugs if the child is already on inhaled steroids to stop what is described as cumulative effect of topical steroids.

Q. What are the Common Questions of Parents?

A child with recurrent or persistent wheeze is a very common problem in paediatric practise and parents normally ask these questions:

- Is my child having asthma?

- Should I avoid certain foods?

- Should the child be put on inhaled long-term steroids?

- What is the prognosis? What should be our response to these questions?

It depends on what other information one has. The child has at least an 80 percent chance of going on to have persistent wheezing througout childhood, if he or she fulfils the following:

- Under the age of three

- Has an asthmatic mother

- Father smokes

- Child has eczema

- Child has had frequent episodes of wheezing not associated with viral infections.

In this case, the child should be treated with an inhaled steroid.

There is no evidence that dietary measures influence the short-term or long-term outcome.

Q. What are the Recent Advances in the Management of Acute Severe Asthma?

One should regard acute asthma in a child as failure of health professional management. If that happens, then the treatment should be with high dose 2 agonist bronchodilator, which can be given either by nebuliser or by spacer. A dose of 2.5 mg of nebulised salbutamol is equivalent to 600 mcg or six puffs of salbutamol by spacer. This can be given frequently and continuously in the beginning of the attack.

It is not necessary to administer systemic steroids by injection unless the child is vomiting or unable to take them orally, because inhaled treatment works just as well and just as fast. The best established dose of oral steroid is prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day given for three to seven days. Some people advocate a once-a-day dose. But the half-life of prednisolone is about 12 hours and therefore it should be given 12-hourly to treat an acute attack. Oral prednisolone, nebulised salbutamol or salbutamol by spacer can be used. In severe asthma, the addition of nebulised ipratropium bromide has been shown to help but not in relatively mild asthma attack. Intravenous aminophylline is undoubtedly effective. It must be done under careful supervision. Oxygen must be given to the child as it is an essential part of asthma management.

Q. Will there be an Asthma Vaccine in Future?

There is lot of work going on in Perth, Australia and Southampton, UK looking precisely at whether a vaccine can be produced. If it is possible to identify a compound arising from bacteria that would drive our immature immunological response towards the TH-1 type response and if that is done safely then there is every prospect of a vaccine. But safety is likely to be the biggest issue as is the case with any vaccine. One can often get the immune system to do what one wants but it does many other things that one does not want it to do. Still a vaccine is a possibility.

Q. What are the Minimum Guidelines for Setting Up Asthma Centres?

What is appropriate in the UK may not be so in India. Yet, the broad principles ought to be the same.

First is the motivation, which means making the diagnosis and stating the diagnosis. If asthma centres are set up widely then asthma ceases to be a worrying disease. It becomes a very common disease readily treatable in centres that do it well. So there is a philosophy that needs to come first.

What one needs in the asthma centre is a doctor (or doctors) skilled in the management of asthma. In the UK, training nurses to help doctors in their job, made a great difference to the management of asthma in children. Doctors often don't have the time to show patients how to use inhalers and to answer questions. The nurses neither diagnose nor prescribe but advise on the use of inhalers. They answer patients' queries whenever possible and check with the doctor in case of doubts. So an asthma nurse is an essential component of the asthma centre.

Further, there is also a need for some sort of lung function testing facilities. Peak flow meters are not sufficient. Now there are good hand-held spirometers that are very reliable and are economical. One should record the spirometer readings i.e. FEV1 and forced vital capacity when children come to the clinic and if they are old enough to do it. Children are able to use the spirometers after the age of six. Under the age of six, only clinical checks may help.

These are some of the fundamental requirements for an asthma centre. But the first and foremost is the philosophy regarding asthma that it is a common, easily treatable disease and when treated in time allows children to lead a normal life.

Long-term Outcome of Childhood Asthma; Prof. John F. Price, consultant paediatrician at King's College Hospital, London, UK. PEDICON 2003.